Floriana station remains the most enigmatic and elusive feature of the Malta Railway. It was the second underground station on the line after Valletta, supposedly opening in 1883 with the rest of the railway and closing with it in 1931. However, there’s increasing evidence that it was not such a clear-cut story, and that the truth is more convoluted.

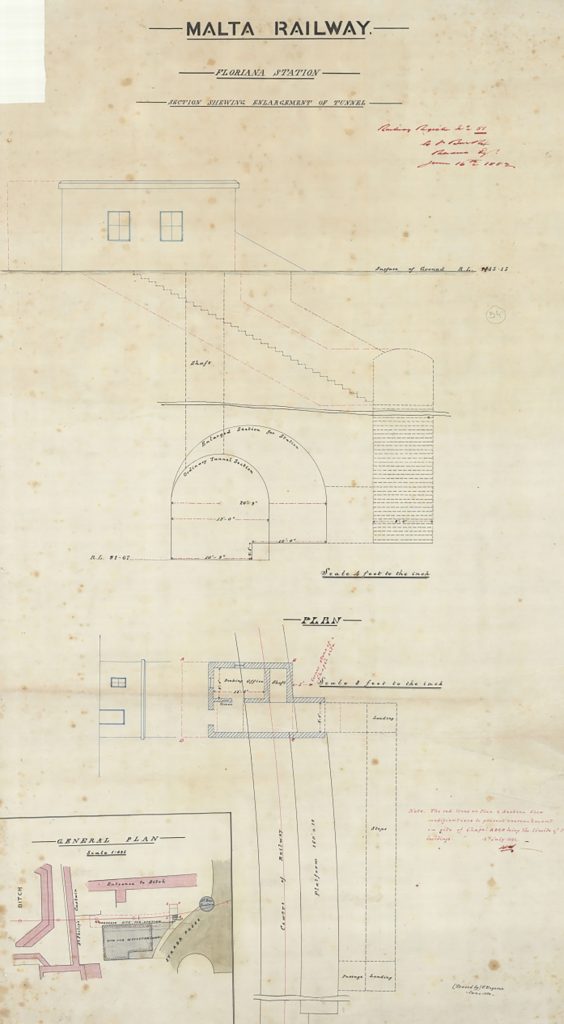

The station was always an afterthought; it was never part of the original proposals and didn’t appear on any plans or section drawings for the tunnel between Valletta and Notre Dames ditch. The first reference to it is in June 1882, when a drawing of an underground station sited virtually underneath the Methodist church was produced. This was located on the south side of the tunnel and would have required a small rectangular ticket office at ground level immediately in front of the new gothic-styled church, equidistant between it and the Wignacourt fountain.

By this time, the tunnel was already about 75% complete, having been started simultaneously from a series of shafts, horizontal headings, and cuttings. The tunnel section where the station would be created was recorded as having already been completed in May, but there’s no indication that the additional width or height to accommodate a station had been implemented. The question is, were 32 weeks sufficient for the new station to be planned, excavated and finished in time for the railway’s inauguration?

None of the newspaper reports describing the opening of the new line at the end of February 1883 mention Floriana. The publication of the first timetable in the Malta Times & United Service Gazette, doesn’t include it, but notes it as an intermediate station. No departure times were provided, but it included fares for each class carried and for single and return tickets from Valletta. From this point until the take-over and reopening of the line by the Maltese Government in 1892 history is silent on the station; it is entirely absent from all other known timetables, not included in notices of fares, and no other references for this key nine-year period have yet been located.

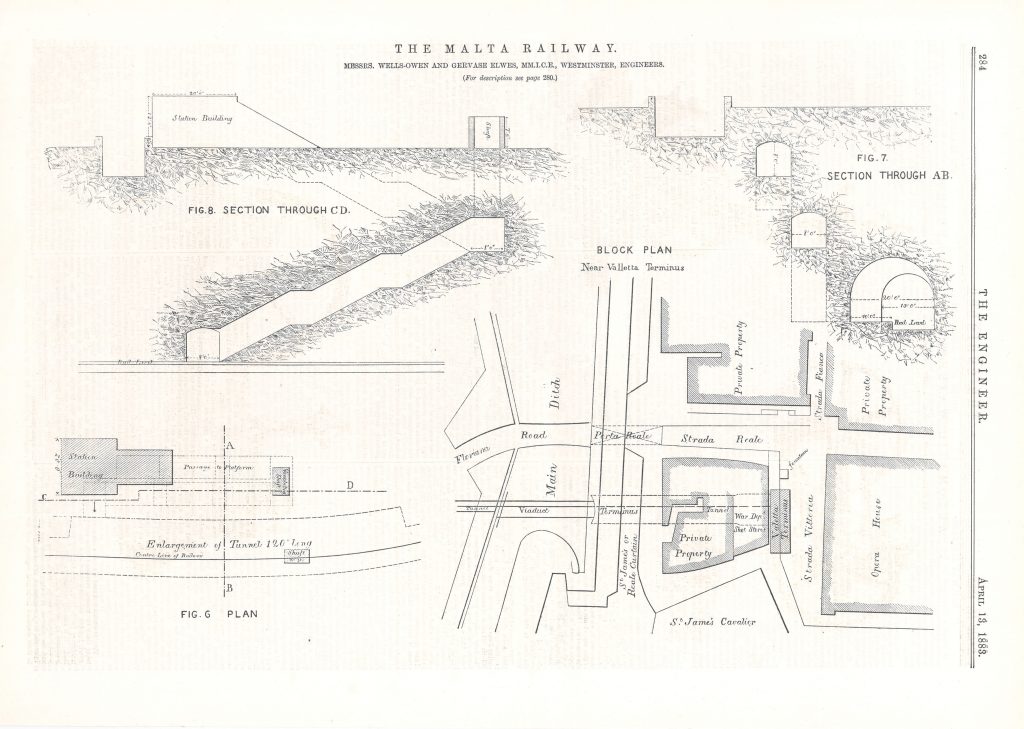

In April 1883 however, shortly after the opening, detailed drawings of Floriana station were published in the auspicious British journal “The Engineer”; These correlate closely with the surviving features at Floriana. After June 1882 the location of the planned station had been switched to the north side of the tunnel. The rather small and perfunctory station building was set far back from the architecturally exotic Methodist church, set so far back as to entirely avoid being captured in the many photographs and postcards recording the new church.

From the small building a passage led down to the underground station platform with a dog-legged arrangement and a series of steps with intermediate landings on its descent. On the drawings, the passage was shown with a shaft at the half-landing, allowing light and ventilation to permeate underground and give passengers temporary respite from the darkness on their way to the trains. As-built, the location and size of this ventilation shaft diverged from the published plan; This suggests that the London publishers were relying on Wells Owen, the British engineers, for drawings, rather than being a first-hand account of the actual construction.

Visiting the tunnel today, there are other anomalies; The half-landing is divided by a large rock-cut arch not shown on plans; the flights and other landings do not correspond in number, size, and rhythm, with either the drawing or the sloping vaulted roof profile. The wall surfaces are rough and might be considered unfinished, a feature matched by the platform walls. Some of these peculiarities might be explained by later alterations (there was certainly work undertaken to convert the station to bomb shelters), or a rushed and cash-strapped job in the run-up to the railway’s opening. But, not all of these oddities can be explained this way.

This, then, is the first puzzle: Was this Floriana station ever completed or did it never open? We know that at various times Guard Hut No.1, situated in Notre Dame ditch, close to Porte des Bombes, was a customary boarding place for passengers despite never being a scheduled stop. Was it this that served instead of the underground station? Why is the station so poorly documented?

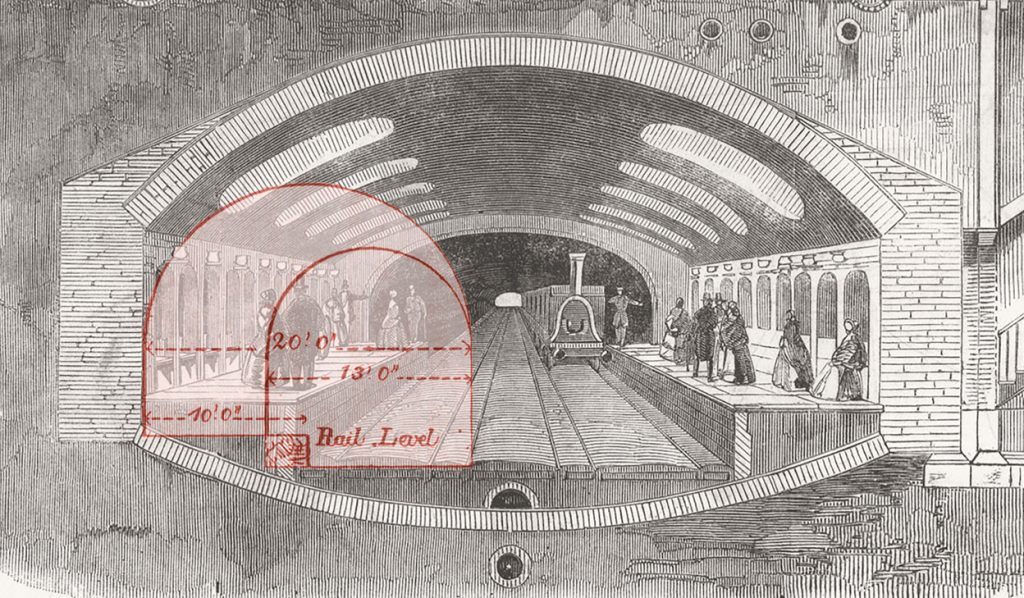

Doubtless, had it been followed, the original Government requirement for locomotives to consume their own smoke would have helped conditions in the underground station. Engines on the London Underground condensed their steam, and coke or smokeless coal was burnt to reduce the smoke they produced; neither option was available on the basic Malta Railway engines commissioned by the Company.

Unlike the generously scaled underground stations on the Metropolitan Railway (electric traction had not yet led to the development of the familiar narrow tube station design), the enlarged excavation at Floriana was short and only marginally larger than the tunnel itself. Hot gasses, soot, ash, sulphur and steam would have been funnelled against the roof of the station roof vault directly towards passengers on the platforms. Provided with just a single vent at the eastern end, the station would have been unbearably smoky, particularly with fires being stoked to raise steam enough to take the punishing gradient up to Valletta. On paper therefore, it was a terrible design.

At what point the shortcomings of the design were realised is unknown. If it was before the locomotives arrived for testing in October 1882 then progress on the station was already well advanced. If it only became apparent when the line came into use, then this was a major and foolhardy oversight. Either way, the station would have been an unpleasant prospect for passengers who valued their lungs as much as a soot-free appearance, and alternatives were needed.

The regular use of Guard Hut No.1 was confirmed in April 1894, two years after Government had recommenced services. When Council member Mr Vallone, on behalf of Floriana residents, claimed they were being denied the use of the railway, saying they had to go either to Porte des Bombes or Valletta to board the train. Clearly, had Floriana been open in the old Company days, it was not in use at this time.

In response, Gerald Strickland promised to find an “alternative site for a station after consulting the military authorities, the present one near the Wesleyan Church being incommodious and dark”. In fact, the development of a new station had been one of the recommendations made in May the previous year by the railway’s manager Lorenzo Gatt as part of a report marking the first twelve months of Government operation.

The report is interesting for the clarity of the description. In it Gatt recommends “that a station be constructed at Floriana” and states “I propose that three or four large openings, like the one outside Porta Reale, should be made in the length of the tunnel: one to be excavated near the Wesleyan church in Floriana, with flights of steps or ramps at its sides, to be used as a station for that town.”

An appendix to Gatt’s report allocated the sum of £550 for an “opening near the Argotti Garden and construction of a station for Floriana”. The sum included for:

- Cutting rock 70ft x 20ft x 30ft = 42000 cubic feet @ 2d – £350

- Construction of ramp 250ft @ 10s – £125

- Building of walls etc. 2050 cubic feet @ 4d – £34.3s.4d

- Laying concrete 300 @ 6d – £7.10s

- Contingencies – £33.6s.8d

Confirmation that these works were executed arrives from the official colonial report presented by the Island’s Governor to the British Government in 1898. Listing a series of accomplishments made on the railway since it was taken into Government hands, he proclaims “a new station was cut in the rock at Floriana”, but doesn’t state when that had been.

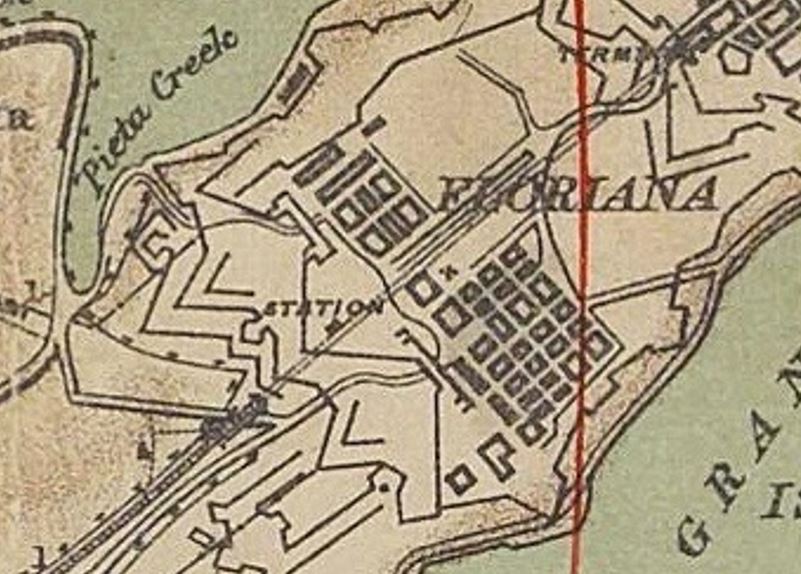

A window of four years between 1894 and 1898 seems likely for the works. Certainly, there was no further mention of new station plans for Floriana, and it seems likely Gatt’s plans had been implemented satisfactorily. A map of 1895, surveyed for the War Office, indicates the location of a station in Floriana but locates it in the middle of St Philips Bastion, and can’t be taken as a reliable record for its site or the date of opening.

The timescales might be further narrowed by a letter of complaint published in a local newspaper in December 1896. It’s author objected to the overcrowded conditions of some trains, complaining “about a dozen people augmented our number at Floriana”, suggesting that the station had reappeared on timetables by this date. This does not absolutely discount this as a reference to Guard hut No.1, but it’s notable that the number boarding was as many as joined at the next station, Hamrun.

The next surviving timetable, published in 1901 is perhaps the first that gives any formal departure times for Floriana. Another documentary confirmation of Floriana Station in this year comes by way of a new-year’s newspaper report of a railway department employee, Mr Vassallo, saving the life of a lady at “the station in Floriana”.

So, if we accept that there was a new station cut into the rock near Argotti Gardens, what is the physical evidence? What did it look like, and how did it operate?

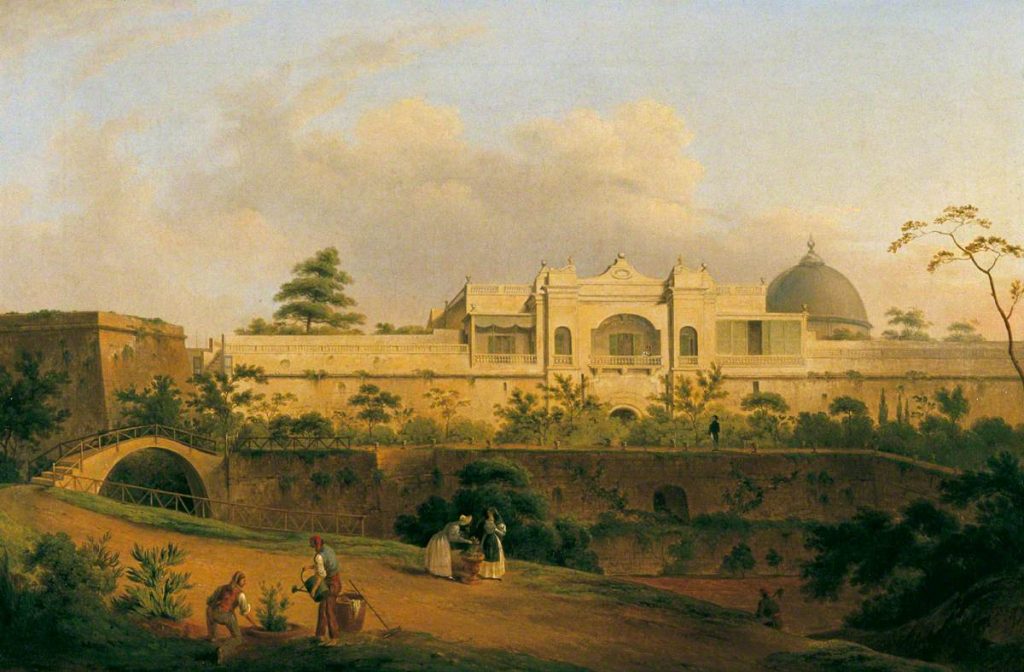

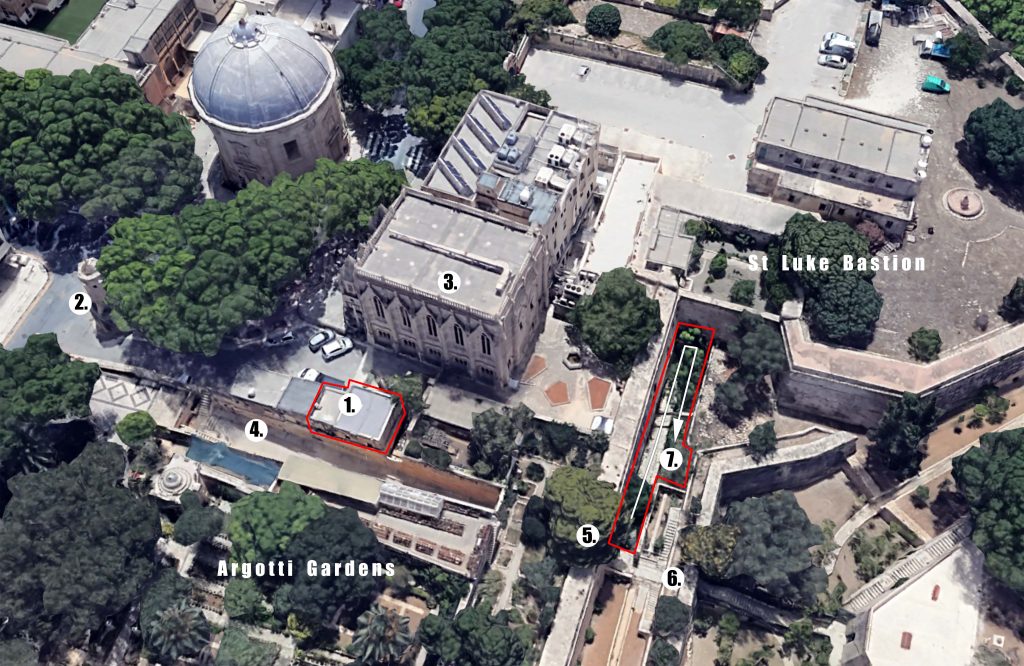

Interlaced into the Knight’s formidable Floriana Lines there are innumerable walkways, steps, gates and tunnels. Amongst these, a ramp descends from a spot next to the Wignacourt fountain, close to the old station site, through a sally port in the curtain wall between St Lukes and St James’s Bastion, and into the ditch separating St Philip’s bastion from the inner circuit of walls. Midway along it, where the ramp passes under the former site of the Argotti Palace, there is a short sally port tunnel that opens out briefly into a narrowly appointed tenaille (an additional, lesser defensive line), before passing through its outer wall with a second archway. This strange interstitial zone off the old ramp and between two sally ports, was where the new station was planned.

Here, parallel to the curtain wall, the back of the tenaille was excavated down to track level on the southern side. Sections of the existing tunnel were enlarged in both directions up and down the line, and along its southern side. Accessing this level, a ramp was constructed. At high level, it spanned the track with stone blocks supported on steel beams. It then cut down through the solid rock before meeting the corner of St Luke’s Bastion and doglegging 180 degrees to continuing downwards. A steel balustrade was provided with arched decorative details. All of this fabric survives today, corresponding with the general description of Gatt’s planned works.

The ramp terminates at the back edge of the widened tunnel section. Here, built into the abutment of the upper ramp section is a small room. A door formerly opened onto the ramp side, whilst the track side has a wider opening with an arched head; perhaps a ticket office? The suggestion is supported by an angled cut in the rock above it that could have received a protective canopy of the sort installed over Attard’s ticket office window. Opposite it across the ramp, mounted on the corner of the rock, a cast iron bracket once supported a lamp.

Aside from WWII blast walls and more modern structures, these are the most obvious station features. The enlarged and widened section of the tunnel is less than 20m in length, long enough to accommodate two full railway carriages and the veranda ends of two others. A careful driver could ensure that four carriages could discharge here through judicious application of the brake.

The overall feel of the platform area is bright and airy, aided by the removal of the tunnel roof further down the line to the west. Unlike the old underground station, it would have needed little artificial illumination between dusk and dawn, and smoke from the engines could disperse more easily into fresh air.

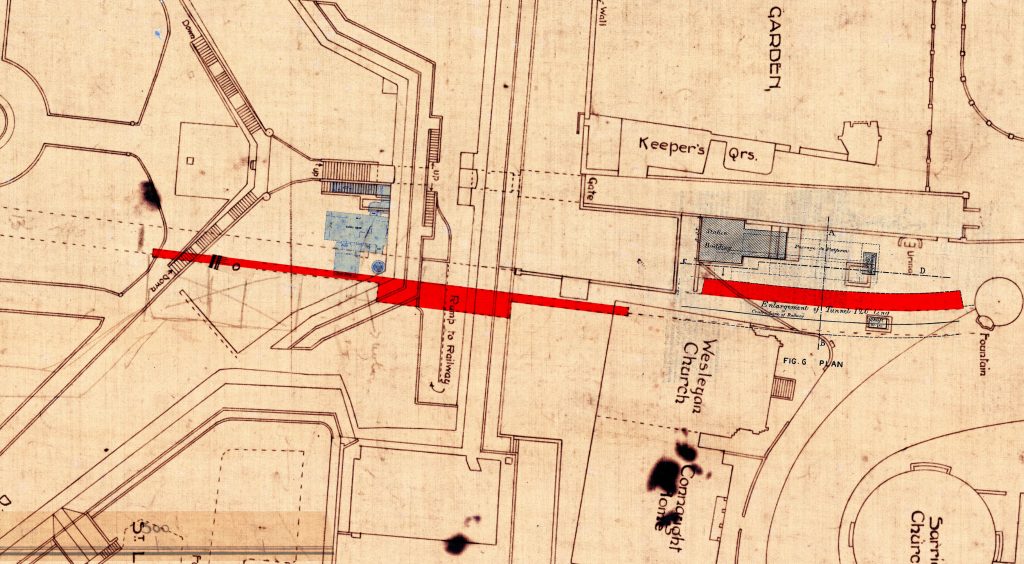

Oddly, Floriana is not documented with the same comprehensive series of measured drawings enjoyed by any of the other stations on the Malta Railway. There are barely any in the otherwise rich collection of railway drawings held by the Maltese National Archives. One that does survive, a blueprint probably drawn originally in the early 1920s, provides important evidence in support of the ‘new’ station (Although it includes the nearby Congreve Memorial Hall of 1932, this detail was added later).

Of the ’old’ station, the small building is shown along with the smoke/light vents being shown in their accurate locations. A dashed line shows the line of the railway tunnel, but includes neither the widened section to accommodate the old platform nor access passages. Other dashed lines detail the arrangement of the two sally ports in the curtain walls with some precision.

The accuracy of the plan is furthered by the inclusion of fine details like the steps and antechamber of the original Victorian guardhouse built to defend the railway tunnel. Clearly marked is the “Ramp to Railway” as well as the opened-out section of the tunnel dashed in below. Another line at the bottom of the ramp indicates the platform edge drawn as a solid line where it was exposed to the sky and continues in dashed form under the fortifications. However, this dashed line extends BEYOND the 20m extent of widened section and continues into the tunnel in both directions.

The dashed line extends to a total of 69m. At either end, it returns back to the tunnel wall, but then pushes further back into it, adding a subtle but important 60cm, around two feet, to the standard tunnel width. This series of dashed lines prescribes the full extent of the station platform. It could have accommodated trains of nine carriages in length. Whilst the wide central section could only serve four carriages, the narrower sections allowed passengers to alight comfortably onto a 1.4m deep platform, part projecting 3ft out into the tunnel like the old platform, and part recessed into its back wall.

Returning to the physical evidence, this theory is supported by close scrutiny of the tunnel fabric. The scooping-out of the south side of the original narrow tunnel has been obscured by post-closure changes, but can still be seen. For example, looking through the steel gates that now close-off the tunnel in the direction of Hamrun, the irregular section profile, deformed outwards on the left side, can be seen. At ground level, a line of damaged stone blocks is likely to be the remains of the platform, obscured or removed along much of its length elsewhere. In the direction of Valletta too, there is a clear cut taken out of the south side.

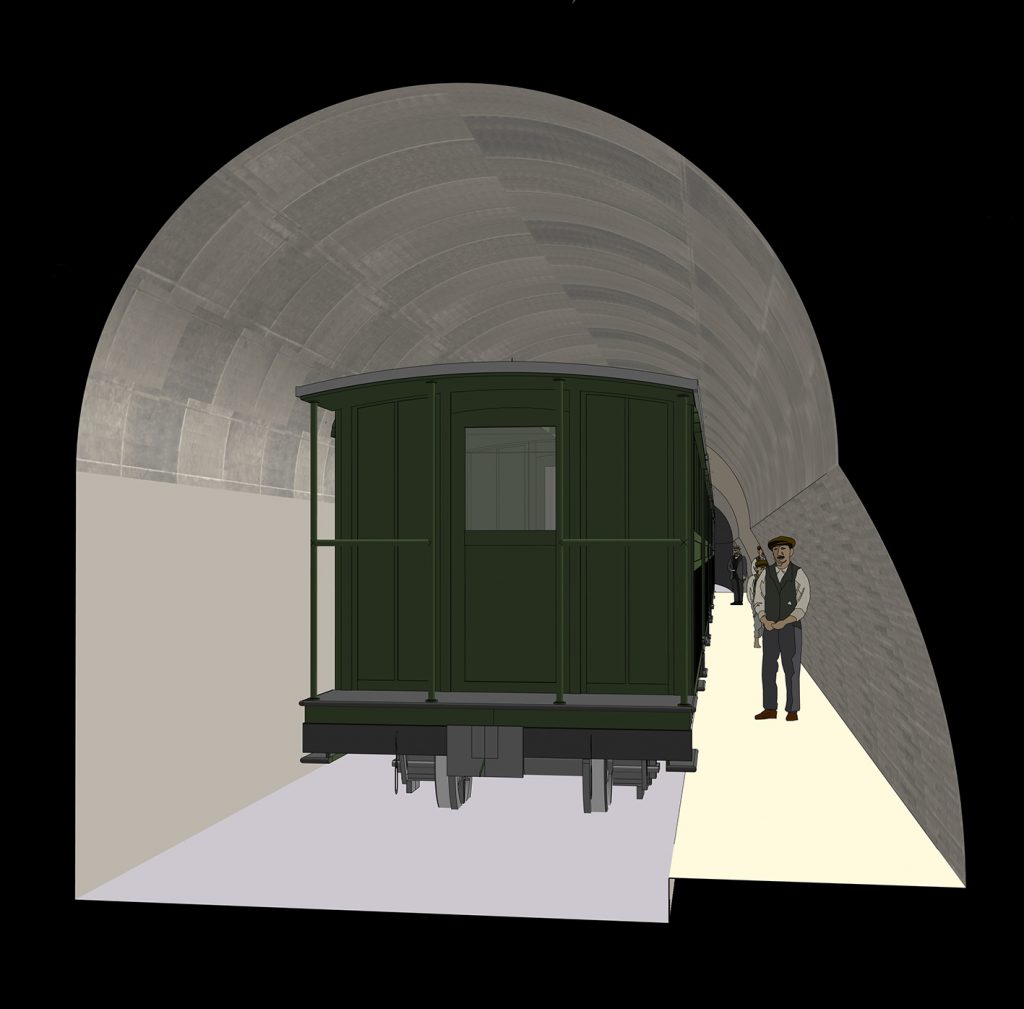

Such a narrow platform in proximity to moving trains, and in the confines of a tunnel, seems dangerous and uncomfortable today. To test whether it was possible, I’ve modelled the arrangement shown on the blueprint, the tunnel, and a train to the same scale. With the train aligned on the centre-point of the tunnel, the added width allowed adequate space for people to move past it with relative ease. With station staff on hand to manage people and ensure the platform was clear before departure, safe operation of this intermediate station would have been possible.

It should also be remembered that passage along the Malta Railway trains was possible from carriage-to-carriage. As with modern railway practice in the UK, where short platforms are encountered, passengers can be directed to the best carriage to alight from. Passengers waiting to board a train needn’t have used the narrow sections unless the arriving train was overcrowded.

Whist not supporting the theory with any useful detail, two tragic accidents were reported at the station that might be explained by its unique layout. Both accidents involved railway apprentices from Hamrun in near-identical circumstances. In each accident, one in 1910 and another in 1913, young men were thrown against the tunnel wall “while attempting to reach the platform of the Floriana station while the train was passing through at ordinary speed”.

It would be unfathomable as to why men familiar with the railway would have tried jumping down to track level from a moving train in a confined narrow section of tunnel with no clearance; serious injury would have been entirely inevitable. But where they knew a platform to be, their behaviour seems more explicable. Even at the narrow platforms, if misjudged, they’d be thrown against the tunnel wall and ricocheted back into the side of the train; had they jumped at the ‘old’ station they’d have fallen flat on the platform.

There remain questions that might one day be solved with new research, or excavation of the ‘new’ station. Where, for example, is the notice of the new station opening? Surely, the Maltese papers would have made some record of its inauguration, maybe even a description? Does more of the platform survive under later rubbish, and can it be traced over more of the 69m suggested by the blueprint?

No responses yet