Progress overtakes: 1910-1931

The competition enters the ring

The last two decades of the Malta Railway’s history, its final act, would be determined in the political arena. Although well regarded as an essential public service, the decline in it’s fortunes began some time before. In 1902, Lord Strickland, the Railway’s highest profile advocate, had resigned his position in government and left Malta to become Governor of the Leeward Islands. This left the way open for an ill-considered development that would prove disastrous to the railway: the Malta Tramways.

In Strickland’s absence Macartney and McElroy, a company with international experience in building electric tramways, secured a concession for a new network in Malta. Originally, this was not supposed to conflict with the Government’s existing railway service but without Strickland to oppose them they managed, in 1903, to secure not just this but the monopoly on any form of electric traction for a period of 99 years. The tramway began running in February 1905, with the line between Valletta and Birkirkara via Hamrun following in a matter of months. There was now direct competition over the most profitable stretch of the line.

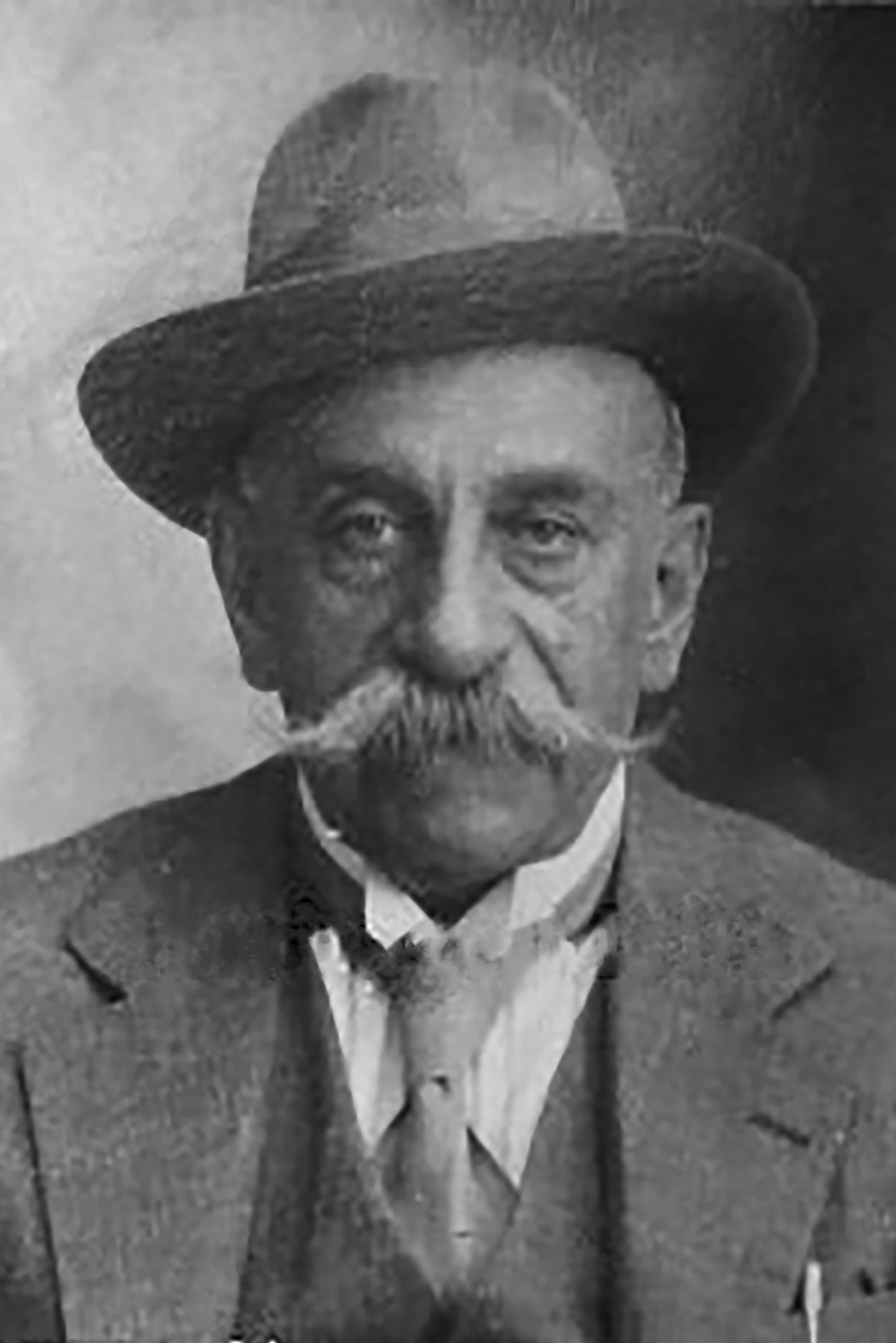

The impact on the railway was instantaneous. As competition bit, income, which had steadily risen to £9,929 in 1905, was down almost £1,200 the following year. Trams on the Birkirkara route were a halfpenny cheaper than the train fare. Nicola Buhagiar was now faced with a railway that was losing money for the first time in more than a decade. Apart from three years between 1905 and when the closed in 1931, the railway would now find itself operating in the red, reliant on Government subsidy to stay open. Buhagiar fought hard against competition, finding new ways to attract passengers back to the railway and trying to economise as best he could to minimise losses. Between 1907 and 1913 he managed to cut an astonishing 33% of the railways operating costs.

Tightening the belt

All fuel for the engines had to be imported into Malta. The railway was reliant on coal to run and was vulnerable to fluctuations in price. Beginning at Hamrun in 1911, one of Buhagiar’s innovations to reduce this dependency was the manufacture of coal briquettes from coal dust and tar; this was reported to have saved about £115. Clinker waste from the engine fireboxes started to be sold to the public as fuel. More income was derived from mounting an 800 gallon water tank on one of the ballast wagons for water to be sold to farmers to irrigate fields alongside the railway. Also in 1911, the Railway looked into the use of petrol railcars to reduce reliance on coal and to secure vehicles more economical to run, particularly for less busy off-peak services. The idea was never progressed. Despite these cost savings, there were already complaints in the Council of Government that “the loss is such that can no longer be borne”

Malta’s historic strategic significance came to the fore again when the First World War broke out in 1914. The Island’s importance as a military and naval station increased, especially around the time of the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. Many more passengers were carried, but a large proportion of this increase was the walking-wounded. Initially, the Railway carried these injured servicemen free of charge until services became so inundated that half-fares were applied instead. The Military hospital at Mtarfa created much of this heavy traffic.

Hoping to contribute to the war effort, in 1915 Buhagiar offered the use of the well-equipped railway workshops and skilled labour at the Hamrun works. The offer was gratefully taken up by the Munitions Committee who ordered hand grenades be produced; These were turned out at the rate of 100 a day. Buhagiar was pleased to boast that, without impinging on maintenance or safety, this had brought income for the railway in excess of £264 in the same year.

Towards the end of the war, in 1917, Lord Strickland returned to Malta and appears to have been aghast at what had been allowed to happen to the railway in his absence. He was shocked that the same elderly engines he’d caused to be purchased from the old company were still operating. He was just as alarmed that the tramway had been allowed to encroach on the line’s territory and the financial impact this was having.

He wrote several letters to the Lieutenant Governor expressing his irritation, at the same time making some constructive suggestions on what could be done to arrest the decline. He recommended the tramway should be brought into Government ownership “to bring the Railway and the Tramway under one economical administration instead of having them in competition which is detrimental to both”. As part of his plan, once this was accomplished, the railway could be converted to electric traction to great economy, and the steam engines could be sold for war use on the Western Front. His suggestions were never taken up by a Government perhaps still focussed on the war effort; With no current official Government role, Strickland was reduced to making representations from the political sidelines.

With an end to the Great War, the usual rhythms of civilian life prevailed again on the island, and attention refocussed on what to do about the problem of the loss-making railway. A report commissioned in 1920, perhaps in reaction to Lord Strickland’s lobbying, advocated the electrification of the railway in defiance of the monopoly the Government had granted to the Tramway. London engineers, engaged to make recommendations, thought that electric carriages could be introduced with one or two trailer coaches to satisfy the traffic demands of the line. Great economies were predicted and profits forecast once more. The capital costs would need to be borne by Government who remained unconvinced the investment would be a wise use of public money. The problem of the railway remained unresolved when, in 1921, a National Assembly brought a degree of self-government to Malta, the questions now being theirs to answer.

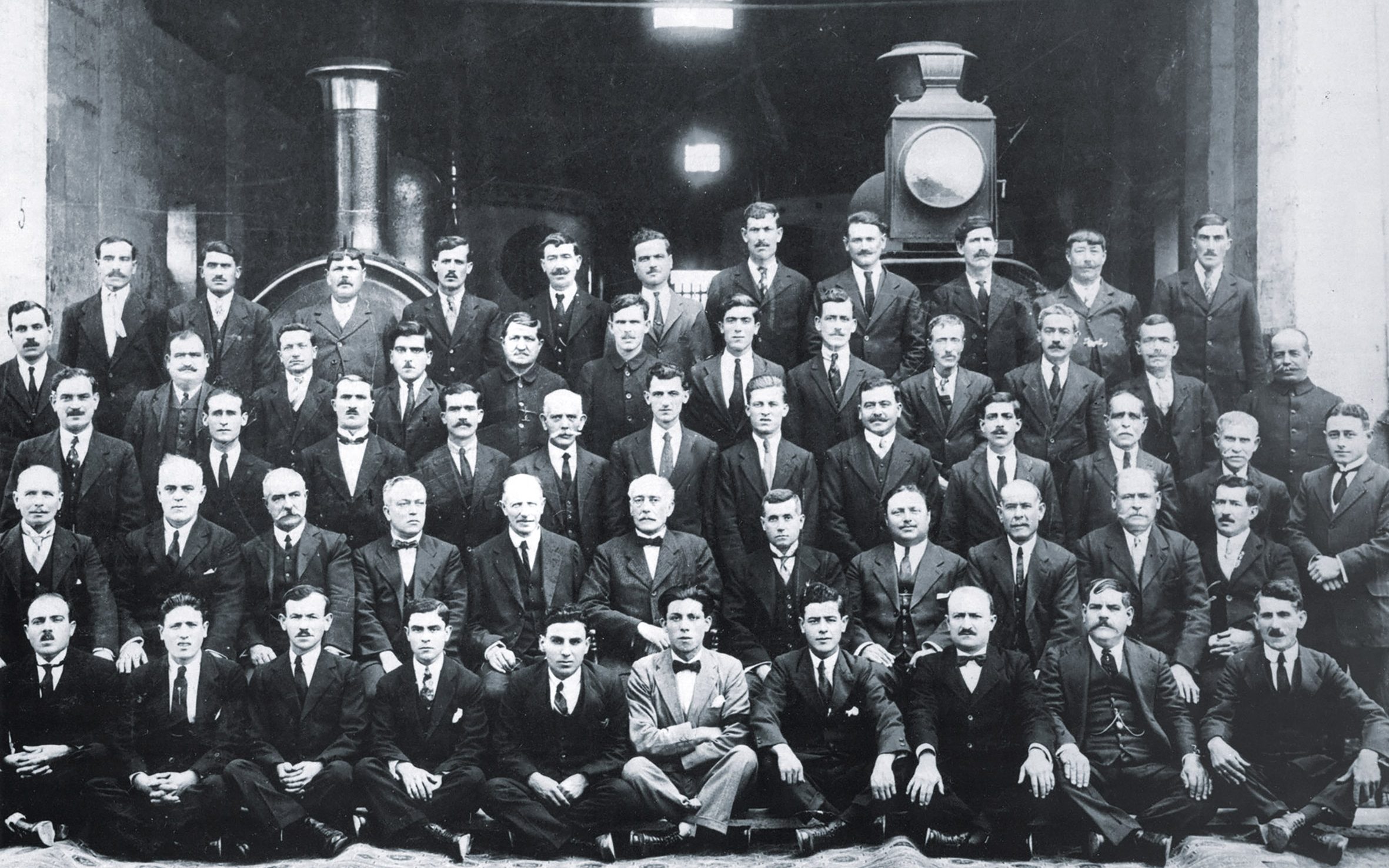

In 1924, on his 65th birthday, Nicola Buhagiar retired. He’d devoted 32 years to the railway, 29 of which as it’s Engineer and General Manager. Lord Strickland led praise of his efforts, particularly his “labour of love”, in creating the station gardens. He described him as an “underpaid and overworked civil servant” and proposed an additional £50 to his pension. The occasion called for many commemorative photographs to be taken with the Railway’s various departments, the largest being the staff, teachers, and apprentices of the workshops and technical school. The school remained a widely-acknowledged benefit to Malta, one perhaps that excused the railway’s continued dependence on public subsidy. Buhagiar’s successor, Carmelo Rizzo, was handed a poison chalice.

Accepting defeat: The final years

Carmelo Rizzo, an architect and civil engineer, was appointed only as acting manager to the railway. Whilst overseeing the railway’s management he retained his other Government position as chief engineer and head of the Water Branch of the Water & Electricity Department. For taking on the additional responsibility of the railway he was granted £200, supplementing his existing £420 wage. After 1926 no railway manager is listed in the Government Blue Book, Rizzo named only in his capacity as principal engineer of the Water Branch; However, he would continue to report on the railway until its closure. It was clear that Rizzo’s was only ever intended to be appointed as a caretaker. Whilst he executed his railway duties faithfully, with his time split between two offices he’s unlikely to have proved an enthusiastic and active proponent of the line’s potential.

The railway carried its largest ever number of passengers in 1926: 1,664,428. Traffic in this year was up 60% on its most profitable year (1905), but with increasing running costs it still couldn’t break even, reporting a loss of £2,827. By this time, in the face of mounting losses and aging infrastructure, Lord Strickland’s view of the railway had changed to one of the pragmatist. From the opposition benches in the National Assembly he expressed the view that Government should no longer be subsidising the line for the benefit of the few who might live along its length (including himself), and it should either commit to investing in it or close it and dispose of its assets. By August 1927 he’d become Prime Minister and found the fate of the railway in his own hands once more.

A second major collapse in railway income occurred in 1928. Although busses had been present in Malta since 1905, they lacked reliability or adequate roads to instil public confidence. After WWI technology had moved on greatly and mass-produced vehicle chassis were arriving in increasing numbers to be re-bodied in Malta and put into service. Without the same infrastructure demands as the railway these quickly became a cheap and versatile mode of transport, capable of reaching almost every part of the island. In 1928 the busses began a more intensive service on the route between Hamrun and Birkirkara. At the same time, the Tramways company dropped their fares in a desperate effort to reclaim customers, but admitted defeat when the busses matched their move, closing operations at the end of 1929.

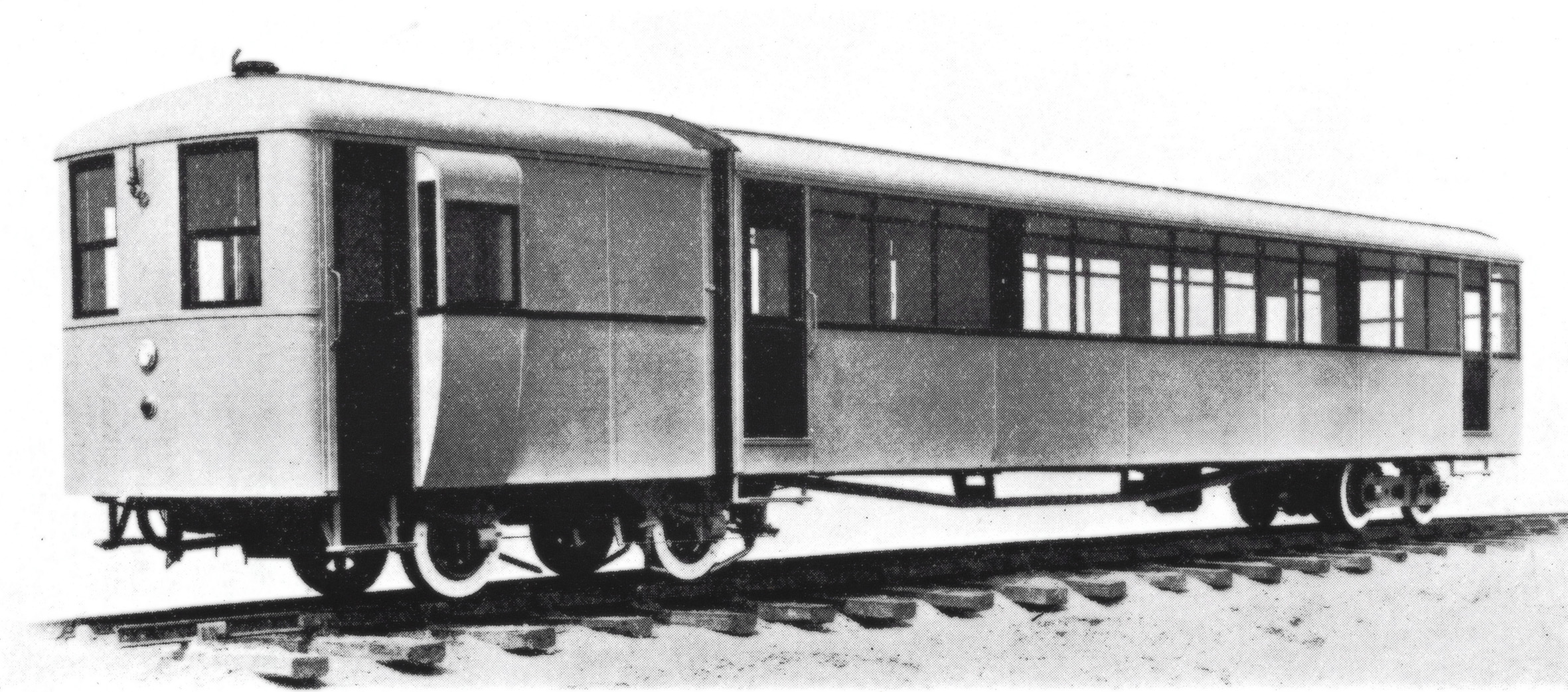

Previously critical of the Nationalist party’s dithering, when in power Strickland found himself hesitating over the future of the railway. Government commissioned more reports, this time from a former vice-president of the institute of Locomotive Engineers, Mr AR Bennett, who’d also been the author “The Locomotive” magazine article on the Malta Railway the year previous. His recommendations were to remain with steam traction, it being, in his view, more reliable. He considered the railway’s main issue to be the loss-making stretch beyond Birkirkara where off-peak traffic didn’t warrant the cost of such a regular service. As a solution he extoled the use of sentinel steam railmotors. These, he observed, had been used to great effect on the railways of the island of Jersey. They could provide fast, economic, and regular services instead of the more heavy, slower trains then in use that were more expensive to run.

Benett’s report was overly optimistic about the benefits of steam railmotors. It was received sceptically by Rizzo, who considered proposals to be based on flawed assumptions. He concluded with the gloomy view that “Everything considered, therefore, the railway undertaking can by no means, in my opinion, be turned into a paying concern.” In Strickland’s belief too, the proposals were disappointing, observing that the use of railmotors in Jersey had only “succeeded in prolonging the life of a decaying railway such as ours”.

Government, keen to divest themselves of the responsibility of running the railway without wanting to be seen as responsible for its demise, looked in 1929 to privatise the concern and invited tenders to run it for an 100 year term under a set of provisos. Only two applications were received, both from local parties, and neither worth pursuing. Instead, Strickland proposed the conversion of the line into a new highway, effectively a bypass to ease congestion on the increasingly vehicle-clogged roads. The Assembly debate on his motion ran out of time, undermined by the opposition’s continued support for the railway.

Strickland tried again with a new motion to suspend railway operations unless tenders for a reduced 20-year period were received by 1st August. It was heavily objected to by the opposition parties and even some of his own Constitutional Party members. The axing of a well-used public service was unlikely to be a vote-winner, particularly for members whose constituencies benefitted from the line. Debate was heated and fractious and the motion only passed with agreement that the use of Sentinel steam railmotors was again considered as an alternative to closure, and that the matter would be returned for further debate if no tenders came forward. The debate was never to happen, eclipsed by political events that saw the suspension of the Constitution and National Assembly, British rule re-instated, and the retention of Strickland and his cabinet in a strictly advisory role to the British Council of Government. In the event, there were no new tenders brought forward, and the future of the railway was sealed.

Strickland was now free to act without the same degree of political hinderance from his detractors, and had already applied himself to the reorganisation and expansion of the island’s bus services as the mode of public transport he considered as the future for Malta. An undeclared decision had already been taken to close the railway, only the final date that services would be withdrawn was left to be published. Measures were taken to ensure that staff on the railway could be absorbed into other Government departments and to protect the technical school as a going concern. On October the 13th 1930, the Traffic Control Board, set up principally to oversee bus reform, reported that the railway should be closed immediately to give way for restructured bus services.

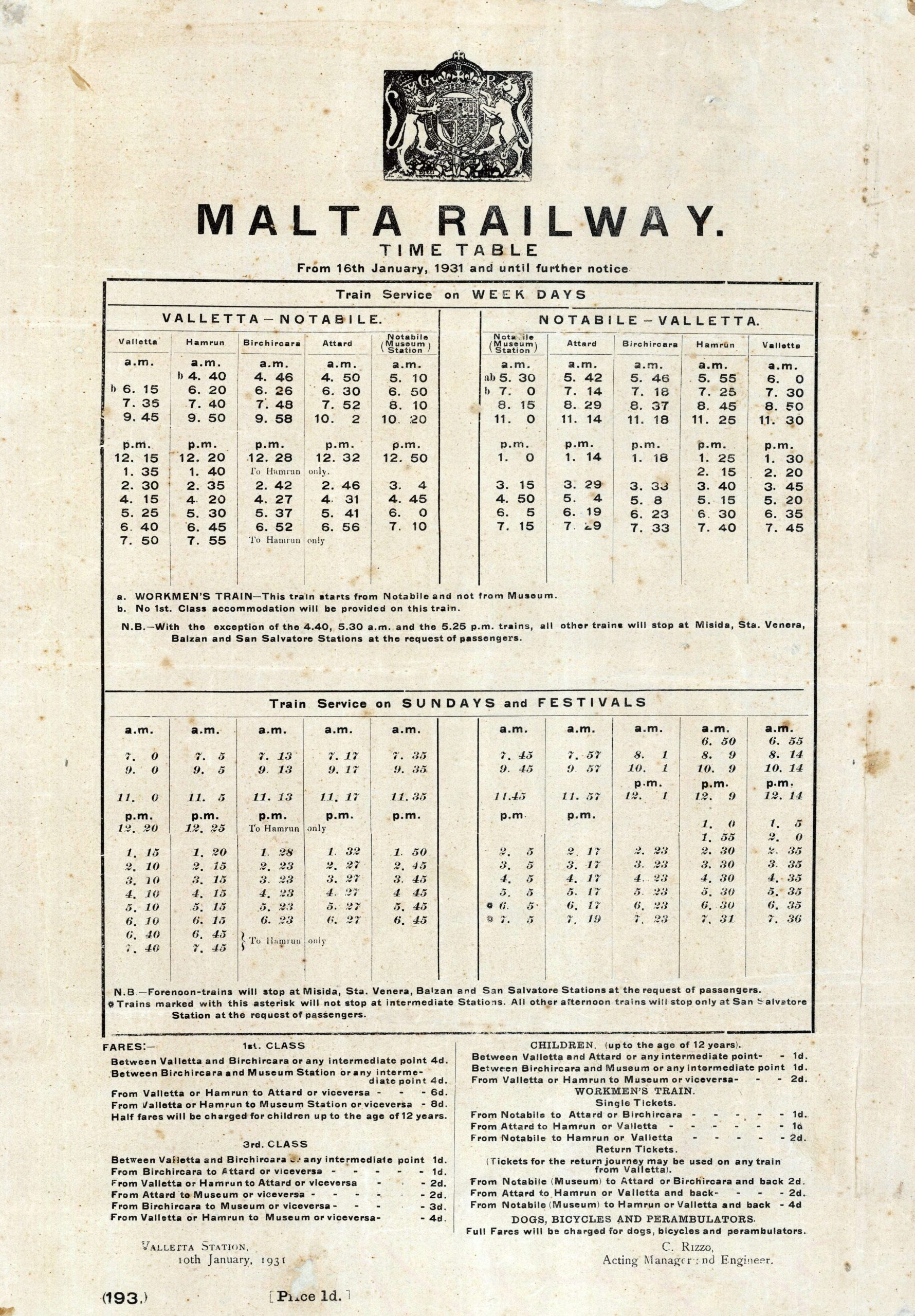

Robbed of any investment the condition of the railway had declined badly. Trains had become unreliable and breakdowns frequent. Unsurprisingly, this had a further impact on reputation and passenger numbers. This running-down of the railway was inevitable in the face of the political uncertainty it had suffered for a number of years. Rizzo was asked by the Lieutenant Governor in November 1930 to advise on ways to keep the railway running a few months more. He reported back on the poor condition of engines and rollingstock; Only three of the locomotives, 7, 8, and 10, were in any way reliable. The decision was taken that a reduced service would be implemented immediately, and timetables were revised at once. Nine services were to run in each direction on weekdays and twelve on weekends and feast days.

For the public the end came somewhat abruptly, less than a month’s notice being given. The Malta Government Gazette announced on the 13th March 1931 that the railway service would be withdrawn in 18 days’ time. Government Notice 98 stated:

“His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to direct that the Malta Railway shall close down at the end of the present financial year, namely on the 31st instant. The railway has for some time past been running at an increasing financial loss owing to the use of other and more convenient means of transport by the public. His Excellency trusts that the organised motor bus services will be able to meet the demands of the travelling public. Those railway employees who will not be given employment in other Government Departments will be retired on pension or gratuity”.

Trains on the final day of service operated beneath a suitably leaden-grey Tuesday sky. There was little sense of occasion around proceedings, no ceremony, no final fanfare. However, there were small crowds of well-wishers, the remaining faithful, who took their last opportunity to ride the railway, some recording it for posterity in photographs: “One party is starting just before lunch from Valletta, halting at San Antonio for lunch and an hour in the gardens among the flowers, thence to Notabile and back by the last – the very last – train. A whole day dedicated to the passing of the Malta Railway”. The Times of Malta was less sentimental, describing at as “despised and ignored, the Malta Railway closes down on April 1st, It has rendered faithful service, and but a short while ago, before the introduction of cheap motor transport, Malta without its Railway would have been unthinkable”. The last word should perhaps be reserved for another reporter’s words, ones that apply equally today as then:

“We will generously forget the railway’s shortcomings and remember only its merits. We will look back indulgently upon its fussy meanderings along the few miles of its length and forget all the minor discomforts attached to the journey”.

The Malta Chronicle and Imperial Services Gazette 7.4.1931

Epilogue

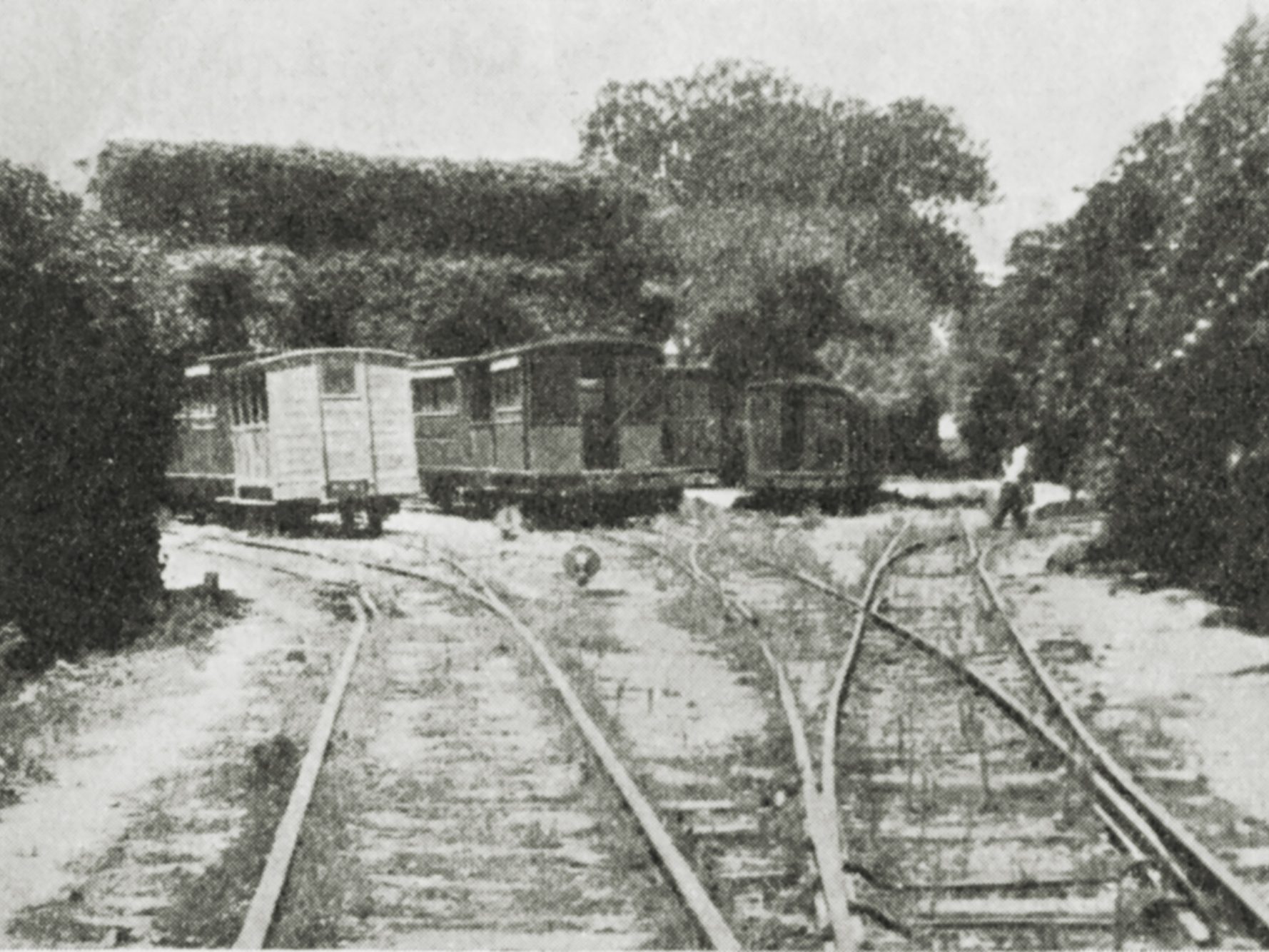

The Railway Magazine published an article in 1934 detailing the demise of the Malta Railway. Effectively an obituary, it observed: “At Hamrun station, the late headquarters, grass now grows high on the points and tracks, but the adjoining workshops are still being put to service as a Government engineering training centre…. A fence across the line forms the barrier in one direction at Hamrun, and in the other the track has now been broken by the demolition of the picturesque bridge over the Sliema road, to allow the passage of double-deck motor buses.” The bridge at San Salvatore had been demolished, 562 tons of steel track had been sold for £1110.11s and lifted; Already, the memory of the line was fading.

After a brief mourning, in April 1931 Government officials had gathered at the Governor’s Palace to pick over the Railway’s bones. Professor William Nixon, Supervisor of the Workshops and Technical School, had the continuation of the school confirmed with allocation of the premises and equipment reserved for continued educational use.

Nixon had asked that some of the locomotives be retained for training purposes and this was agreed. He was asked to select which engines he wanted and seems to have chosen No.2, 3 and 5, but it was ultimately No.1 that was recorded still at Hamrun after the end of WWII. Most of No.3 must surely already have been butchered for spares keeping its sister engines in steam to the bitter end? Although photographed and listed for sale in 1933, No.1 was recorded as surviving at Hamrun in 1945. The fate of the other retained engines is unclear, but the survival of it’s cab steps in the Birkirkara Museum suggests No.5 remained on the island after closure. Had Nixon been a sentimental man, it might be suggested he selected No.1 for preservation as the railway’s pioneer, but what the attraction of its sisters and No.5 might have been is unclear.

Tenders had been invited in 1933 to dispose of the other engines, but the highest bid of £595 didn’t even meet their scrap value. Most rollingstock also failed to sell and everything languished at Hamrun until the proposed development of the Milk Marketing undertaking on part of the site required it to be cleared in 1937. Fresh tenders were invited for the locomotives and they were eventually disposed of, emptying the engine shed and allowing it to be pulled down and replaced by a new concrete office block. It’s believed that whatever was sold was shipped off the island for scrap, but No.1 somehow escaped banishment, shunted outside the original engine shed with a tram body and there still until at least 1945. Tragically, it and the other retained engines eventually vanished at some later date, before any attempt at preservation could be made. Perhaps there are still fragments of these engines left in Malta? Would no one have wanted the brass number or maker’s plates as souvenirs?

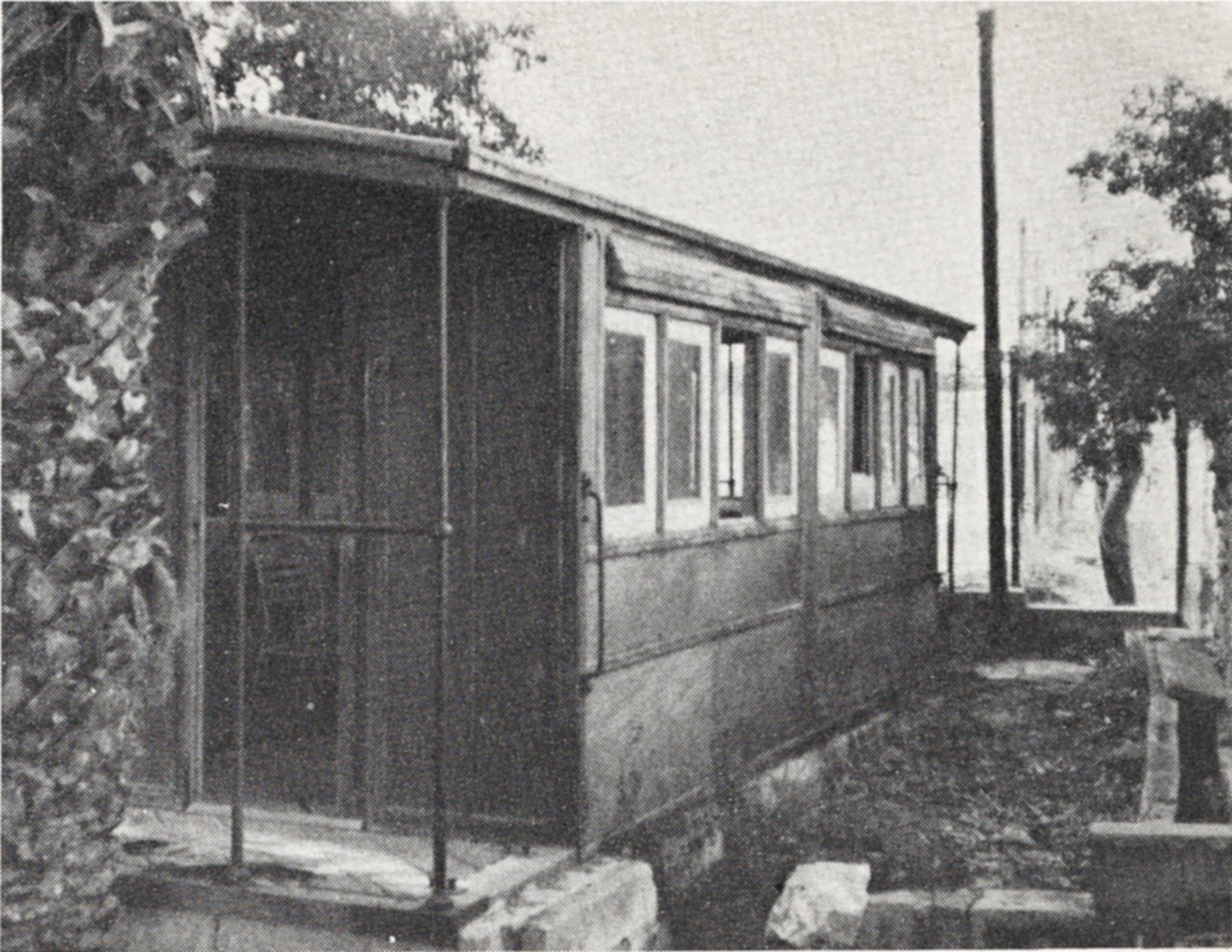

Carriages were reused in a variety of guises in Government use, from waiting shelters for the Gozo ferry at Marfa, to bus offices outside the Auberge de Castile. Some were bought for private recreational use such as beach huts at St Thomas Bay, and including the sole survivor, a shelter in a private garden in Birzebbuga salvaged and set-up at Birkirkara station in the 1980s.

Continued Government ownership served at least to preserve most of the station buildings. Birkirkara, Hamrun, Attard and Museum were handed to the Department of Agriculture and most maintained as gardens. It was responsible too for the infilling of the cutting at Notabile for a new produce market that never materialised. Attard’s building was a war casualty, and, although damaged in the Blitz, Valletta’s surface building survived until the development of Freedom Square in the 1960s.

Birkirkara station was extended upwards by a story by the Office of Public Works in 1935 for Local Government use. It survives today, still surrounded by it’s beautiful gardens, and today home to the Museum run by the Malta Railway Foundation.