Notabile (Rabat)

6 miles, 55 chains – Journey time 27 mins

End of the line, albeit briefly

Despite its importance as the original terminus, any study of Notabile station is hampered by a lack of definitive evidence, either documentary or physical. Unfortunately, the deep cutting dug out for the station in the Victorian period was largely infilled again as part of a plan to develop the land in the 1970s, burying most of the railway structures and obscuring the site’s history.

Even the station’s name is something of a puzzle. By the late 19th Century Mdina was recognised by numerous names. The Italian Citta Veccia, ‘old city’, or the epithet Citta Notabile were both recognised, though, to an extent, had been falling out of use since British rule of the island. Either name could easily assume Rabat, as a suburb, was also encompassed. The more ancient Mdina was also used. Why the new terminus was christened using Notabile is unclear.

The abundance of appellations must have been confusing for the uninitiated passenger, not knowing that their journey to Rabat would actually involve alighting at a station with a different name to that painted on its façade.

The inconvenience of this confusion was little in comparison to the location of the station on arrival. Because of the topography it was virtually impossible to engineer a line to ascend to the level plateau both towns stood upon. One early idea was to form a corkscrew loop with a level gradient to take the train smoothly uphill, like those used in the alps, but this would have proved as expensive a proposal as it was outlandish.

Instead, a compromise location was sought, with a position on Racecourse Road, below Saqqija Hill, settled upon; this required any passenger to make the final 500 yard walk and 150 foot ascent themselves, or rely on a karozzin to carry them to their final destination.

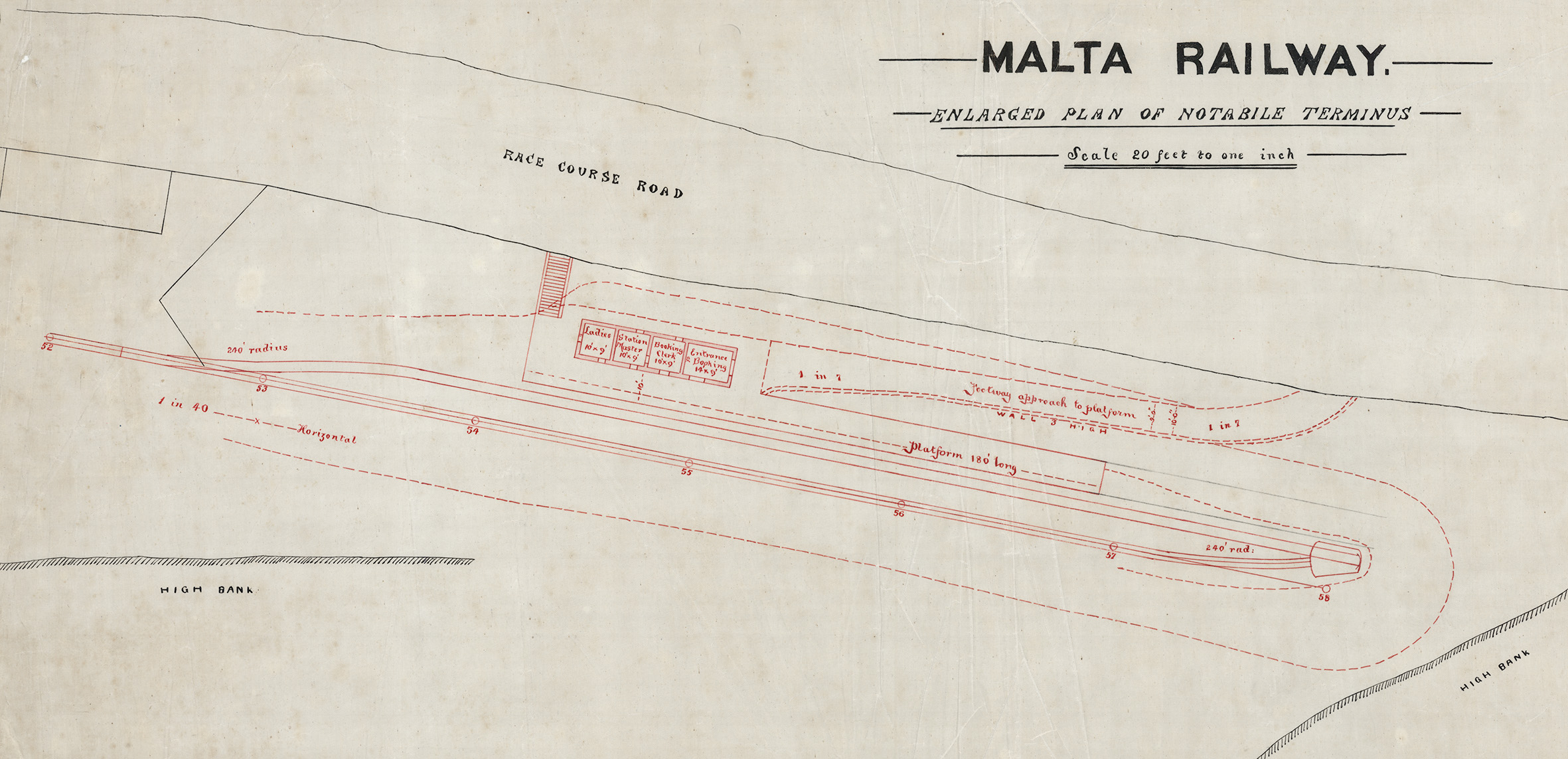

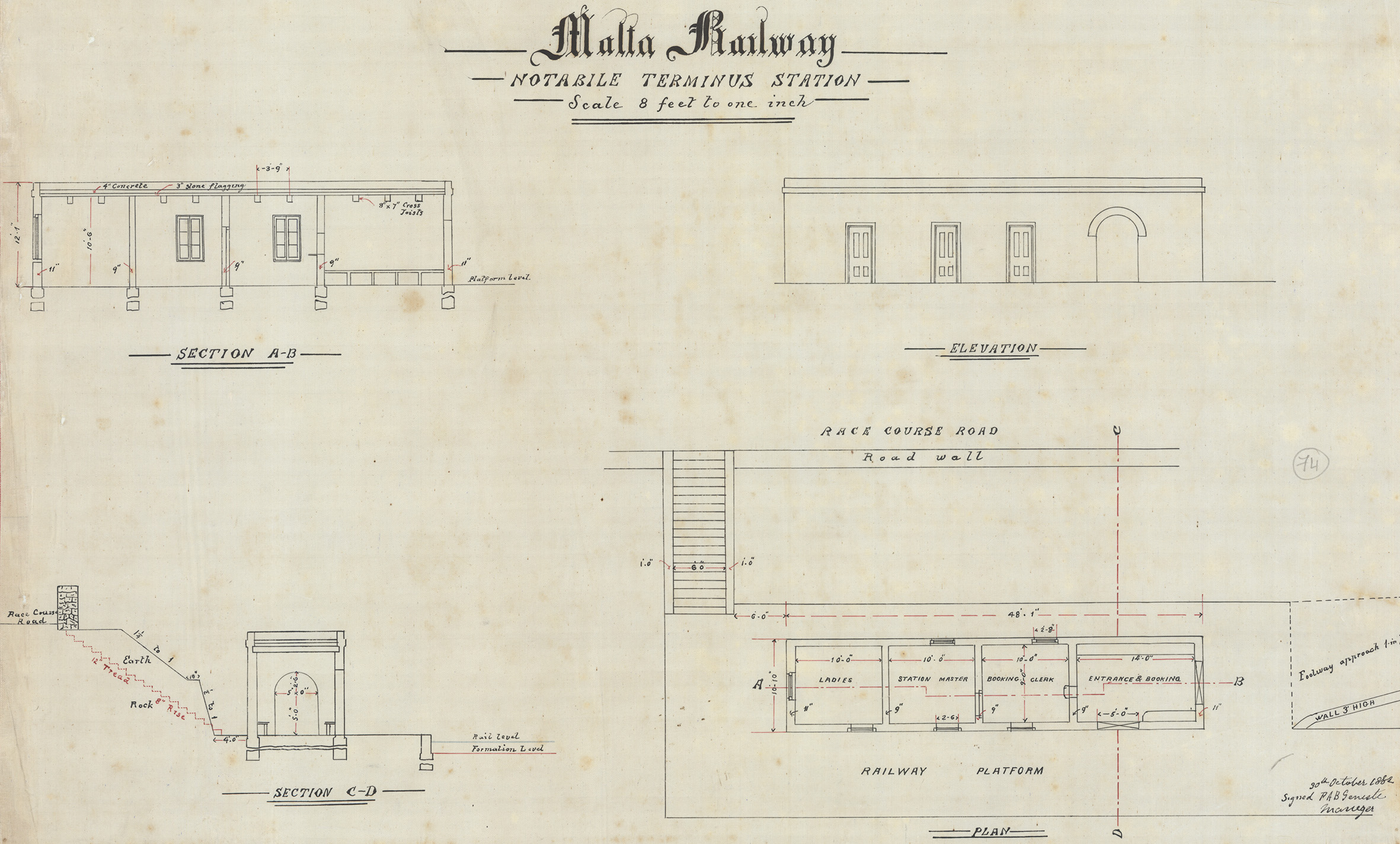

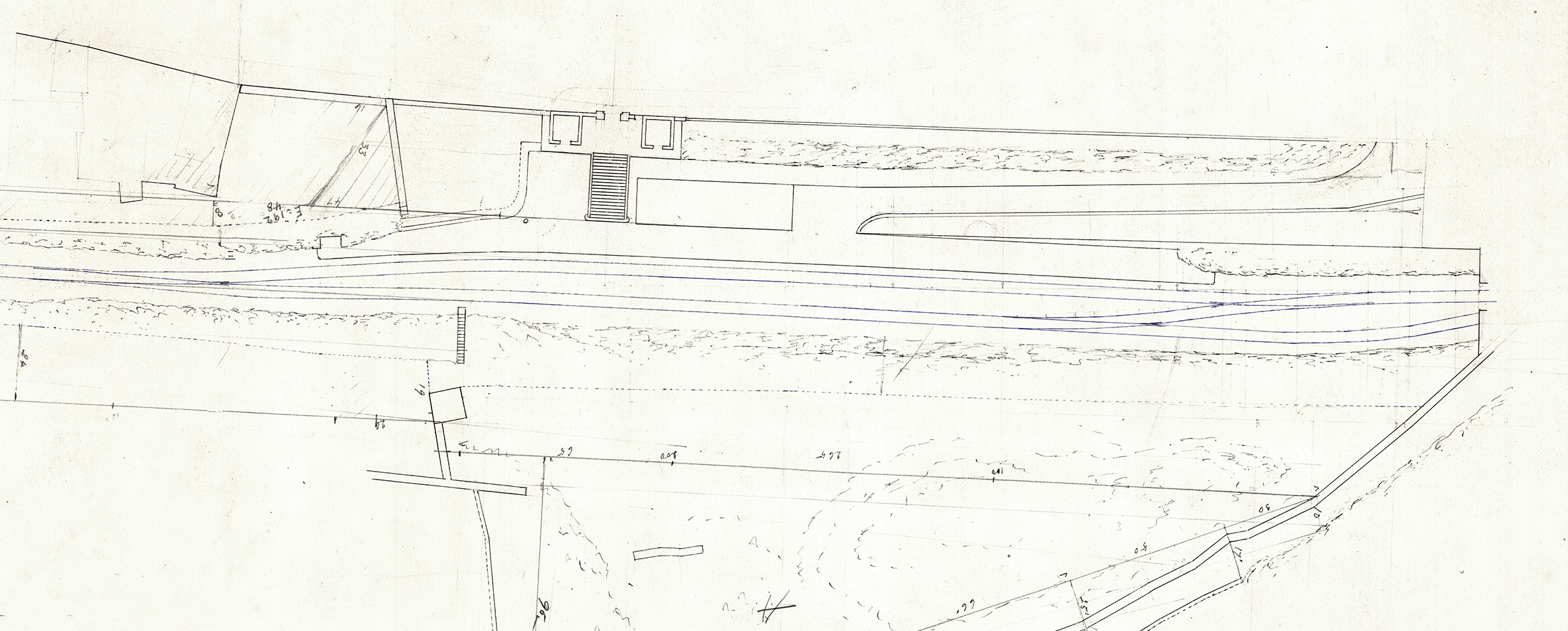

The gradient required the station to be quarried deep into the hillside. A wide cutting was dug, large enough for two tracks, a platform 180 feet in length, and a standard larger station building.

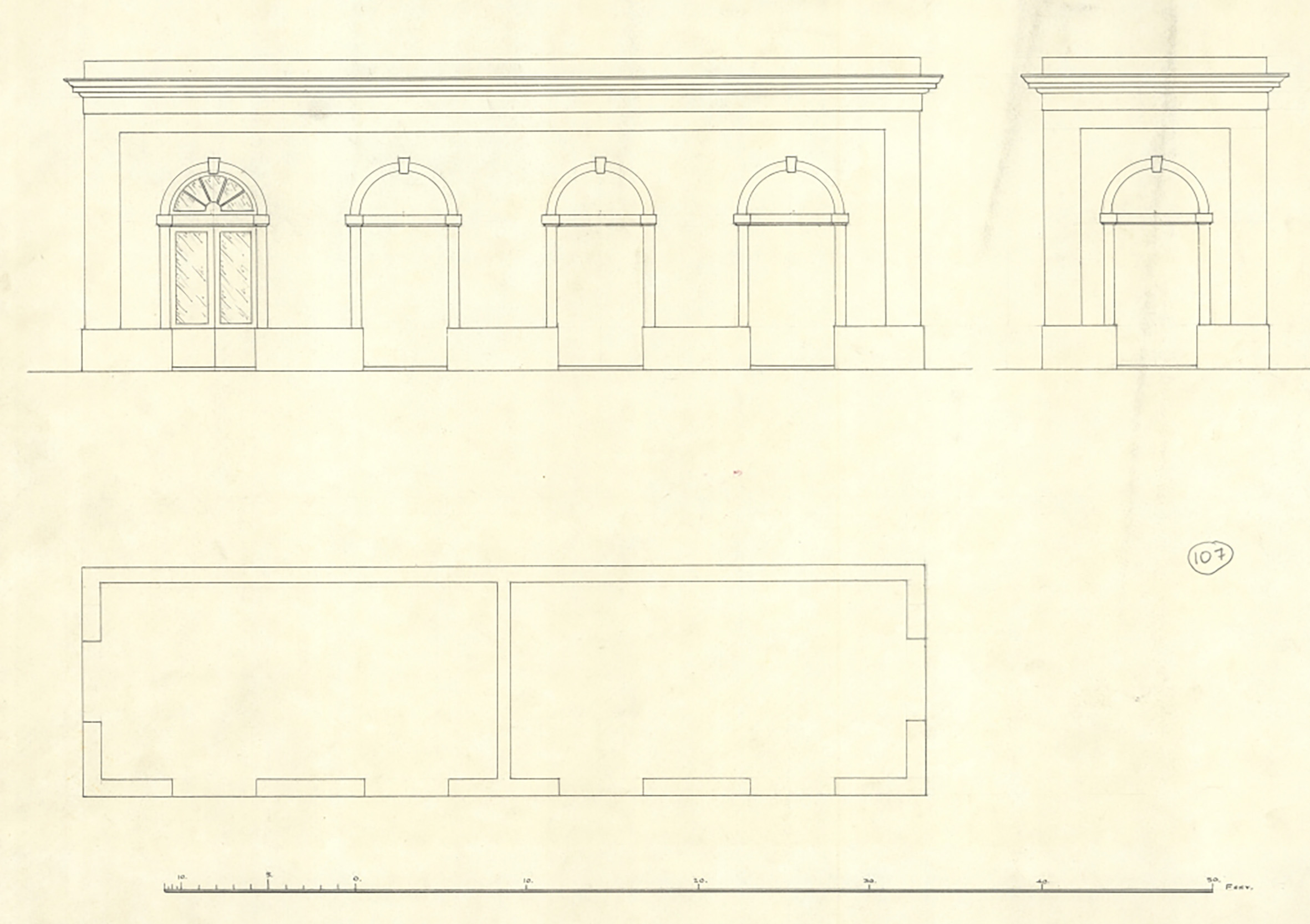

Unlike similar buildings at Hamrun and Birkirkara it had one of its two 8ft wide arches in the narrow end façade. Facing towards the town, this allowed passengers descended a ramp from the road to directly access the small booking office within to buy their tickets. As well as station master and clerks offices, this arrangement and a slightly longer plan allowed for an additional ladies waiting room, a facility the other stations lacked.

Alternative access to the platform was formed by twenty steps down from the road on the other side of the building. As at Valletta, the station was equipped with a sector plate at its far end rather than conventional points to switch locomotives between the platform and passing loop. Like the other terminus, this was a space-saving measure, removing the need to dig a longer cutting to accommodate points and a head-shunt.

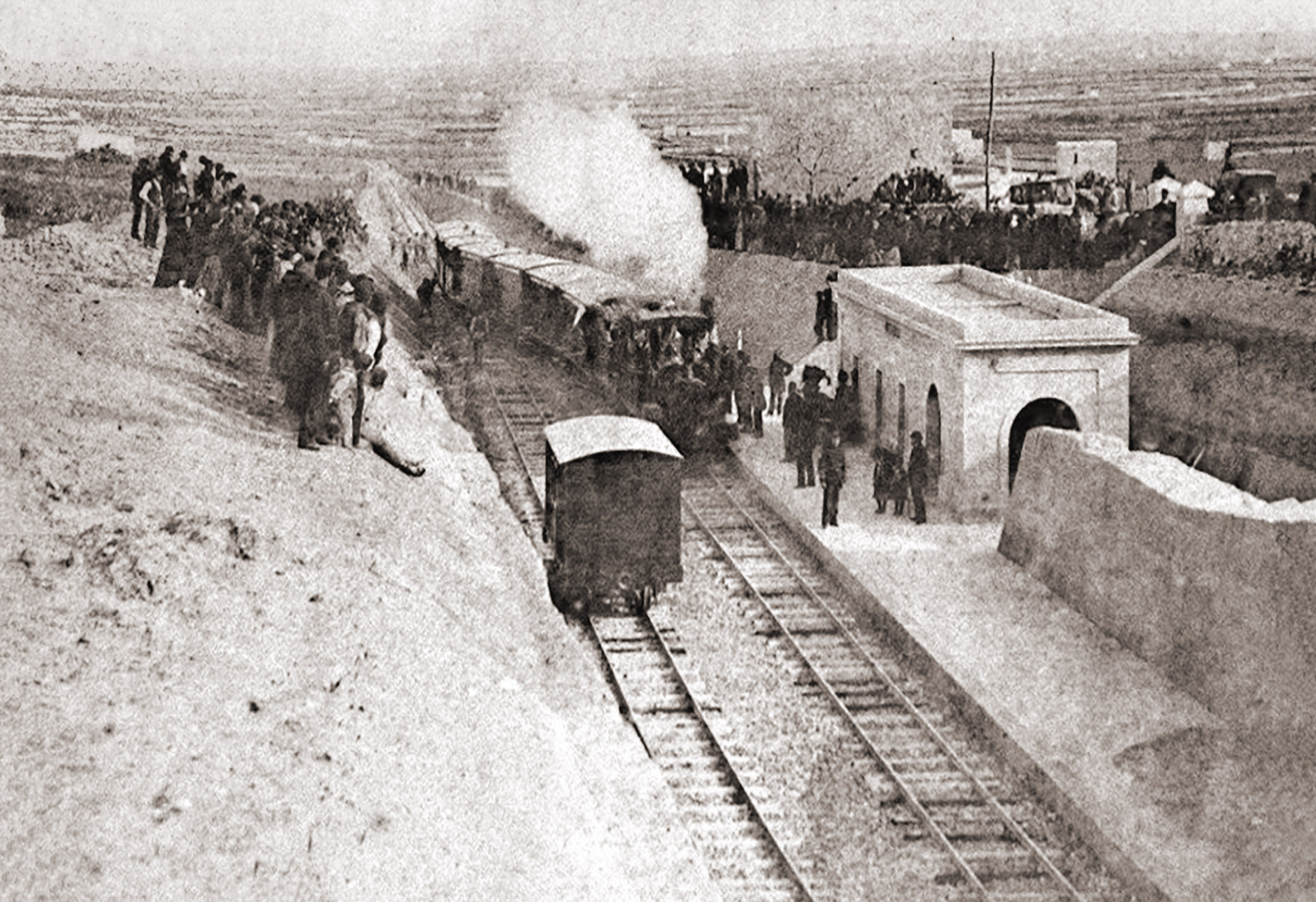

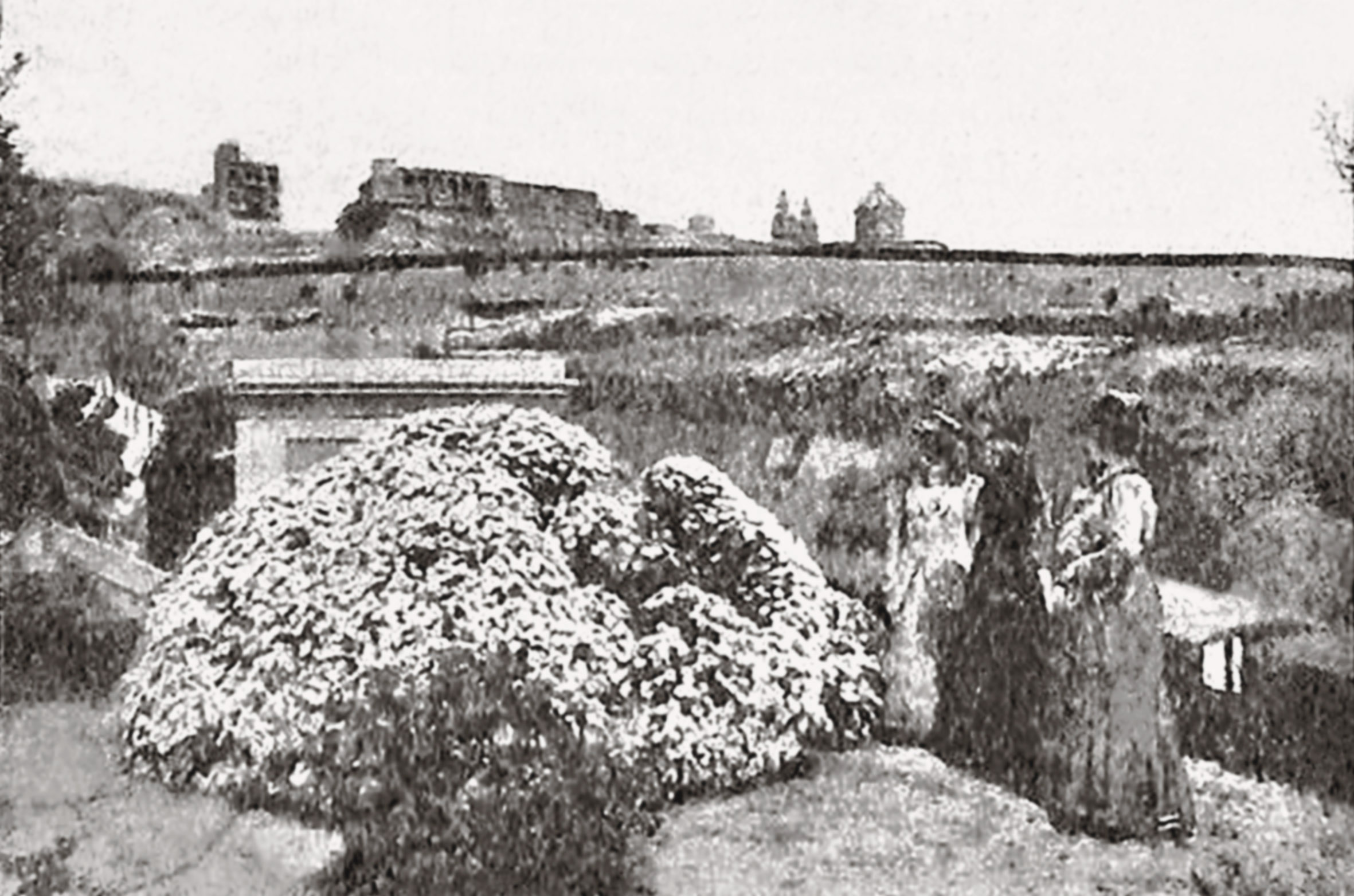

To the misery of investors, construction work had been slow and beset by problems, delaying the line’s opening until 28th Feb 1883. The inauguration provides us with some of the most detailed evidence for the station’s appearance, with a number of photos taken to commemorate the event. The special train, formed of seven carriages, was hauled into Notabile by the first two of the line’s engines suitably decorated. Another carriage, seen poised in the passing loop, must have been physically manhandled onto the back of the arriving train before the locomotives were individually switched into the passing loop to take their place at the head of the return journey. After posed photos of the assembled party the train set back off for Valletta.

The clean sharp appearance of the new buildings in these photos distracts from other details suggesting the railway opened in a less than complete state. Builders’ gangways can be seen descending the side of the cutting, drainage and paving work behind the station building are still in progress, and wide sections of rock between the platform and approach ramp have yet to be dug away.

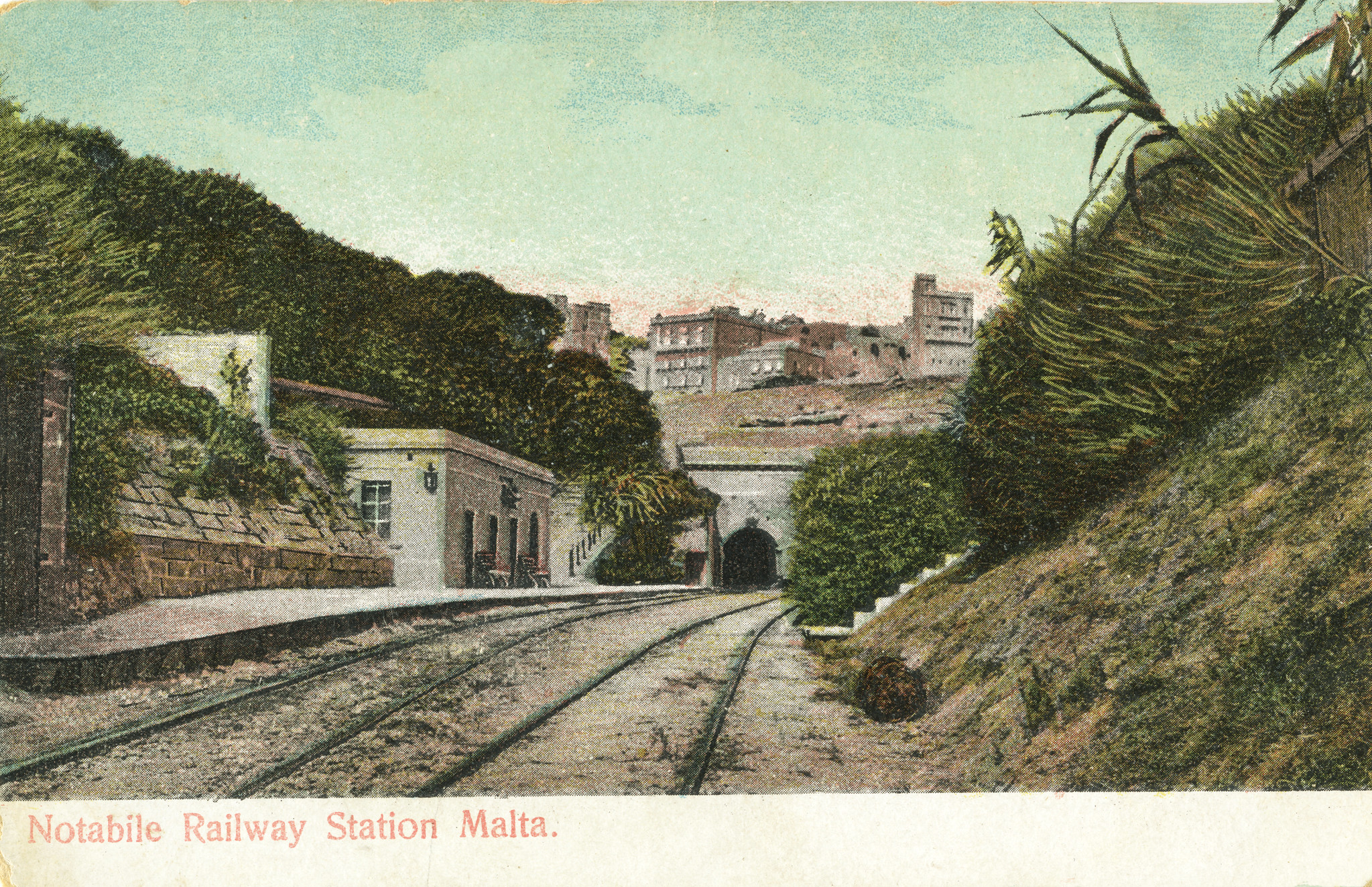

The next time we see the station, in a postcard taken around twenty years later, there have been significant changes, the most obvious of which is that Notabile is no longer a terminus, a new tunnel carrying the line under Mdina and beyond. Following Government takeover, a planned extension to Mtarfa was authorised in 1895, with work commencing the following year to dig the requisite tunnel. The extension opened five years after it was first sanctioned. Gone was the restrictive sector plate, conventional points now accessed the passing loop.

Other changes include the lengthening of the platform and widening of the ramp, but a dense green backdrop and verdant shrubs arrest the eye; no doubt this was one of Nicola Buhagiar’s endeavours to improve the station’s appeal.

More changes had taken place that are less obvious. In 1892, the first year the Government ran the railway, they were acutely aware of the chaos that ensued at the station during feast or race days. Each of these occasions saw trains inundated with passengers, many having climbed walls or crossed fields to avoid buying tickets in full knowledge that the crowds would prevent the inspectors passing through the trains.

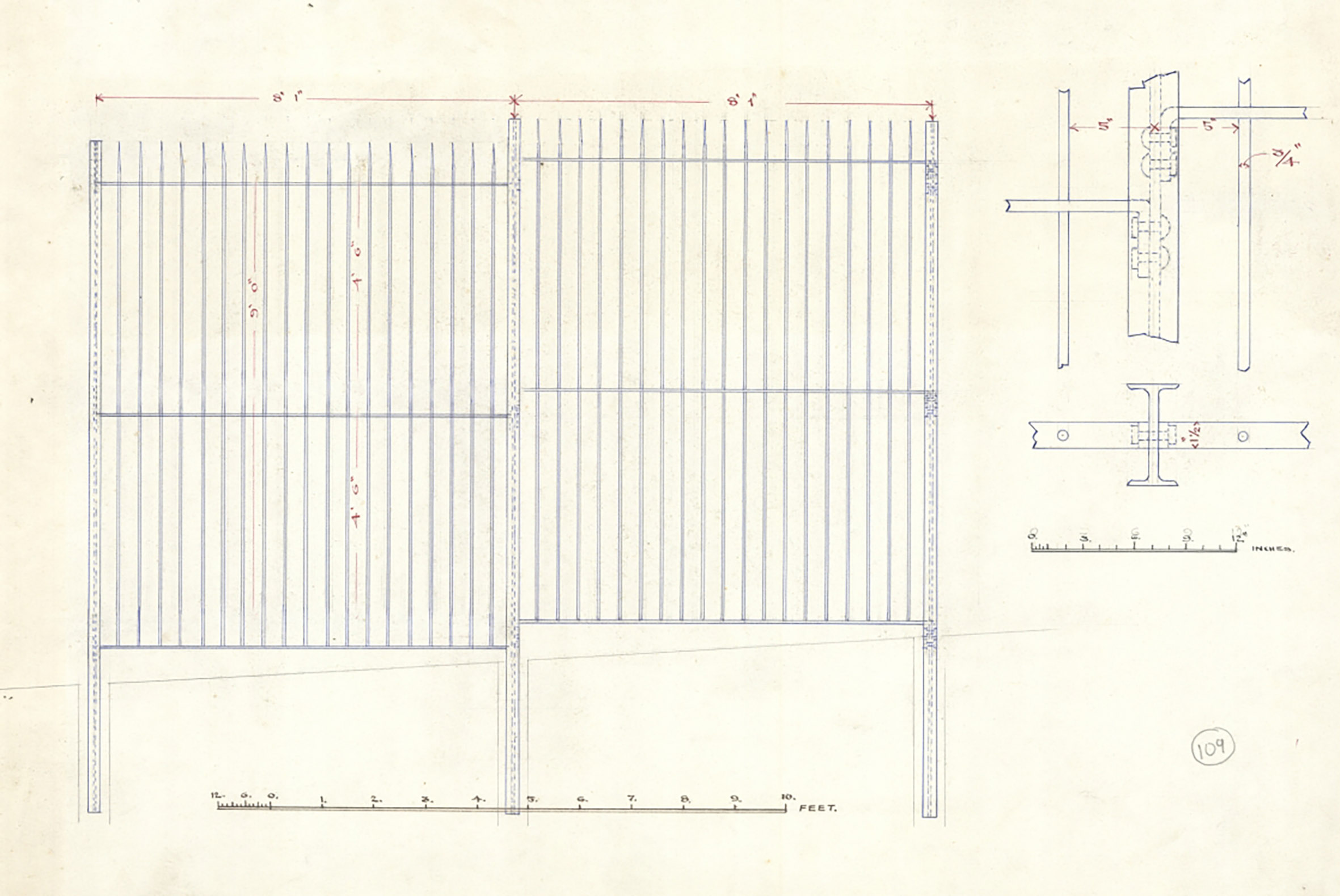

The crowds were so large and boisterous that there were genuine concerns that someone would come to harm. £100 was allocated for the erection of tall steel railings around the whole station in time for the feast of St Peter & Paul that June. Passengers would be kept out of the station precincts and allowed through only until the trains were full. A particularly narrow doorway was installed at the top of the ramp to protect this way into the station.

Access down to the platforms was now controlled by way of ticket office described as “new” in 1893. It stood at the top of the the steps down from the road, the more convenient ramp apparently being reserved only for the exit of arriving passengers. Analysis of the surviving structure suggests that the ticket office, a small single room, remains as one part of the surviving building on Racecourse Road.

A latrine for Notabile was one of the other urgent items manager Lorenzo Gatt had listed in a request to Government for funding in the same year. This was duly erected at the top of the station ramp, no doubt to the great relief of the Karozzin drivers who plied their business from the cab rank there. Looking closely at the present house in the same location, it appears to incorporates some of that earlier building, and some of the station railings can still be seen alongside the road today.

Two verandas had also been planned by Gatt, one on the platform and another for the recently built ticket office at the upper level “as the passengers, waiting their turn to get the ticket, or if they find no room in the waiting sheds, are obliged to remain out in all sorts of weather”. It seems these were not progressed, for in 1904 there were still complaints that workmen locked out of the station before the first train of the day were exposed to the rain and without shelter, and “even inside the station in devoid of accommodation”.

The same complainant highlighted a narrow wooden entrance through which the crowds of workmen surge once the station was opened “the strong push the weak, the tall crush the low of stature, the young are hustled by the grown up: there is no order, there is no one to enforce and preserve order. Pain is inflicted, and accidents even of a serious nature are averted only by chance”. Perhaps in recognition of these issues, the station would shortly undergo more major changes.

The development sequence at the station is difficult to place after this, but dated drawings suggest things began happening around 1905. Initially, the railway planned the straightening of Racecourse Road, a project that it at least partially accomplished; this seems perhaps an unusual move, but the station would benefit from extra land on which it was hoped to erect a new building, one which would have greater street presence, provide better facilities, and increase the control of passengers entering the station precinct.

It’s not clear whether an existing stone entranceway already stood at the top of the steps down to the platform, and if it did, whether this was incorporated into the new building. It’s now thought that a ticket office built in 1892/3 was, supplemented with a partner on the other side of the entrance. These three basic elements, two kiosks and stone entrance, formed the new building, connected by a curtain wall to the street side. The building was raised on a terrace above the station embankment with a wide new set of steps replacing the originals down to the level of the platform. Between the two kiosks the building was completely open to the rear, passengers being protected from the elements by a flat canopy roof. The kiosks probably functioned as a new ticket office and station master’s office. It was, by any stretch of the imagination, an odd building, and without precedent on the railway.

The façade facing the road looks to have been rather plain, blank to the street but for the central arched doorway and a pair of smaller flanking doors. It had a continuous decorative cornice at parapet level but must have looked very austere. To this, whether part of the original design or an afterthought, was added a more satisfying and attractive arcaded loggia front. That it was a later addition is clear from the different stone, change in block coursing, and ham-fisted connection wrought between the two phases. If the carved graffito on one of the piers can be believed, this was in place by at least 1912. At last then, finally, there was some practical shelter for prospective passengers!

Another in this chain of improvements is one not immediately obvious: the complete rebuilding of the platform building. In 1893 Gatt reported these were “very small and damp and uncomfortable”. Only through a careful study of photos does a change in height and character become apparent.

Two surviving drawings may, or may not, be proposals for Notabile. They’re similar in outline to Attard’s later station building, but the earlier date, 1905, and longer narrower plan suggest they were intended for Notabile where the narrow platform restricted any more ambitious development. The arched doorways would have been rejected in favour of the square-headed openings on construction.

The reconstruction is perhaps not surprising; similar original buildings at Hamrun and Birkirkara were both condemned for their cramped conditions and general inadequacy, and were rebuilt in 1910. Certainly, the relocation of the ticket and station master’s offices to the new roadside building would have focussed attention on what to do with the old structure to bring it up to standard.

The new layout, divided in two down the centre of the building, is likely to have incorporated first class and third class waiting rooms. Strangely, and despite the earlier complaints, Notabile was the only station on the Malta Railway not known to have a platform canopy for shelter.

So, the evidence suggests the station was completely reconstructed from 1905 onwards, with the loggia frontage completing the works a little time after. By 1913, the year the platform was crowded with delegates of the International Eucharistic Congress, the station was in its final form.

Notabile settled into a regular daily pattern of arrivals and departures: around fourteen trains in each direction. This had dwindled to just nine by 1930, the last full year the railway operated. Eventually, after a prolonged agony of falling receipts, services stopped entirely after 13st March 1931.

The station buildings and platform survived in new uses for a time including as a strategic fuel store during WWII, and was still in a decent state of preservation in the late 1960s before plans for a new agricultural market on the site; significant investment was literally ploughed into the cutting to form a level foundation. Reputedly the lower station building was buried rather than demolished, so may survive under tons of overburden. Thankfully, the project was eventually abandoned, but not before much damage had been caused.

The upper station building survived the onslaught and, with its arcades and shelter infilled, was converted to a house. Recent study has shown that the building survives surprisingly well inside. The mouth of the tunnel leading under Mdina survives significantly encroached upon by the 1970s rubble and the extension of a house that developed around the old latrine building on Racecourse Road. Though it’s suffered, there remains great opportunity to reveal and preserve what survives of the original terminus of the Malta Railway.

Previous Station / Next Station