Museum (Mtarfa)

7 miles, 70 chains – Journey time 29 mins

A boost from the barracks

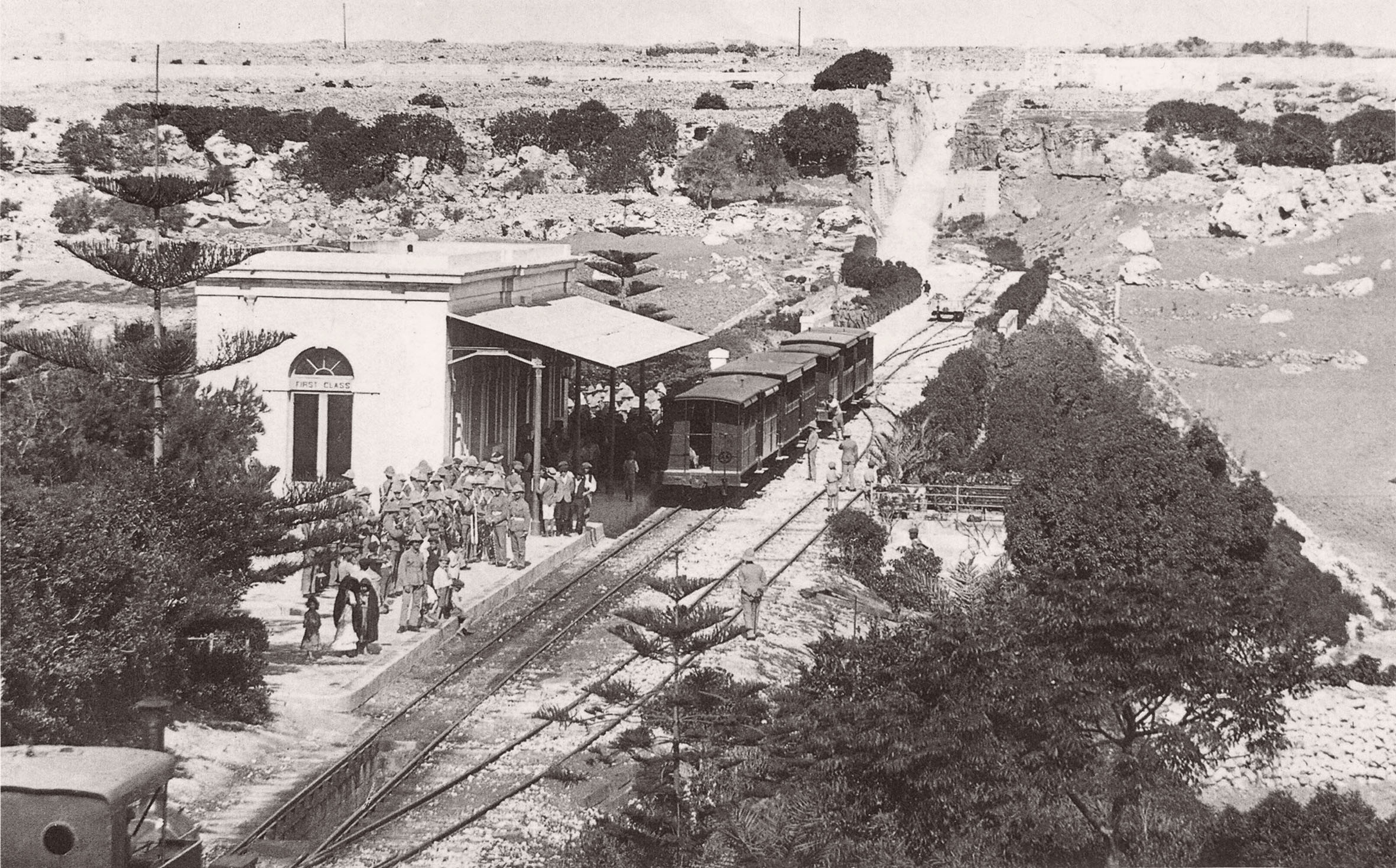

Many photos survive of Museum station, more than any other on the line. Its location below the ancient walls of Mdina gave it a picturesque backdrop, but its proximity to the British army barracks at Mtarfa guaranteed the popularity of postcard views; soldiers billeted there keen to share a flavour of their stay with relatives back home.

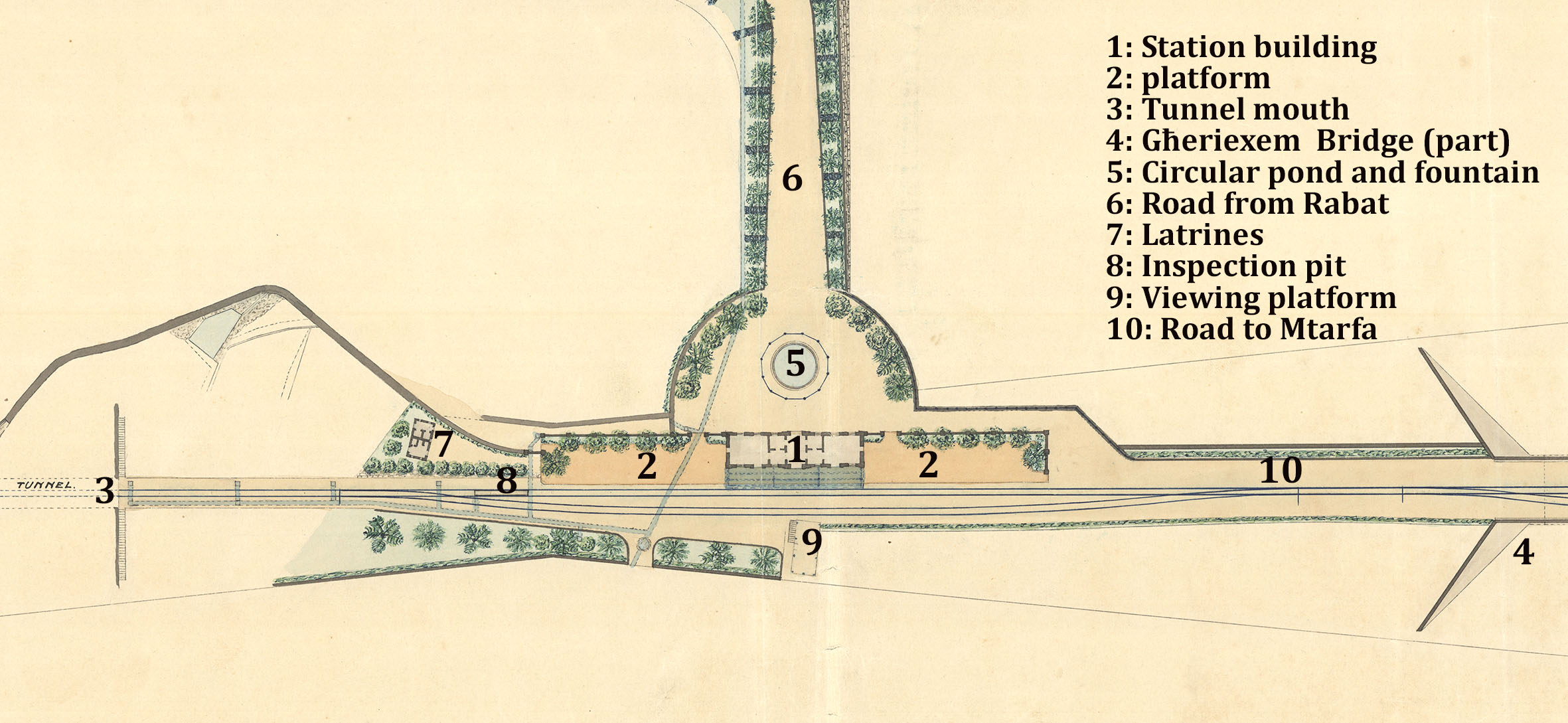

Museum station, named after the Roman villa museum nearby, opened in 1900 as part of an ambitious extension of the railway. A tunnel was burrowed under Mdina from the original terminus at Notabile, the spoil used to create a huge new embankment spanning the Għeriexem valley. As well as accommodating the new station and railway line, this provided new level road access to Mtarfa barracks, part of the Railway’s business plan to attract soldiers to use the new station; Although it was downplayed, the railway’s extension to Mtarfa had strategic military importance. The army, though, made no contribution to the costs.

The ascent to Museum through the tunnel from Notabile was challenging, engines having to work hard to draw their trains up to the new station where the line levelled off. The embankment and Għeriexem bridge was a hopeful first-step in the railway’s long-held ambition to extend a line as far as Marfa and the Gozo Ferry, but the long siding that ran across it never took it onwards into another tunnel.

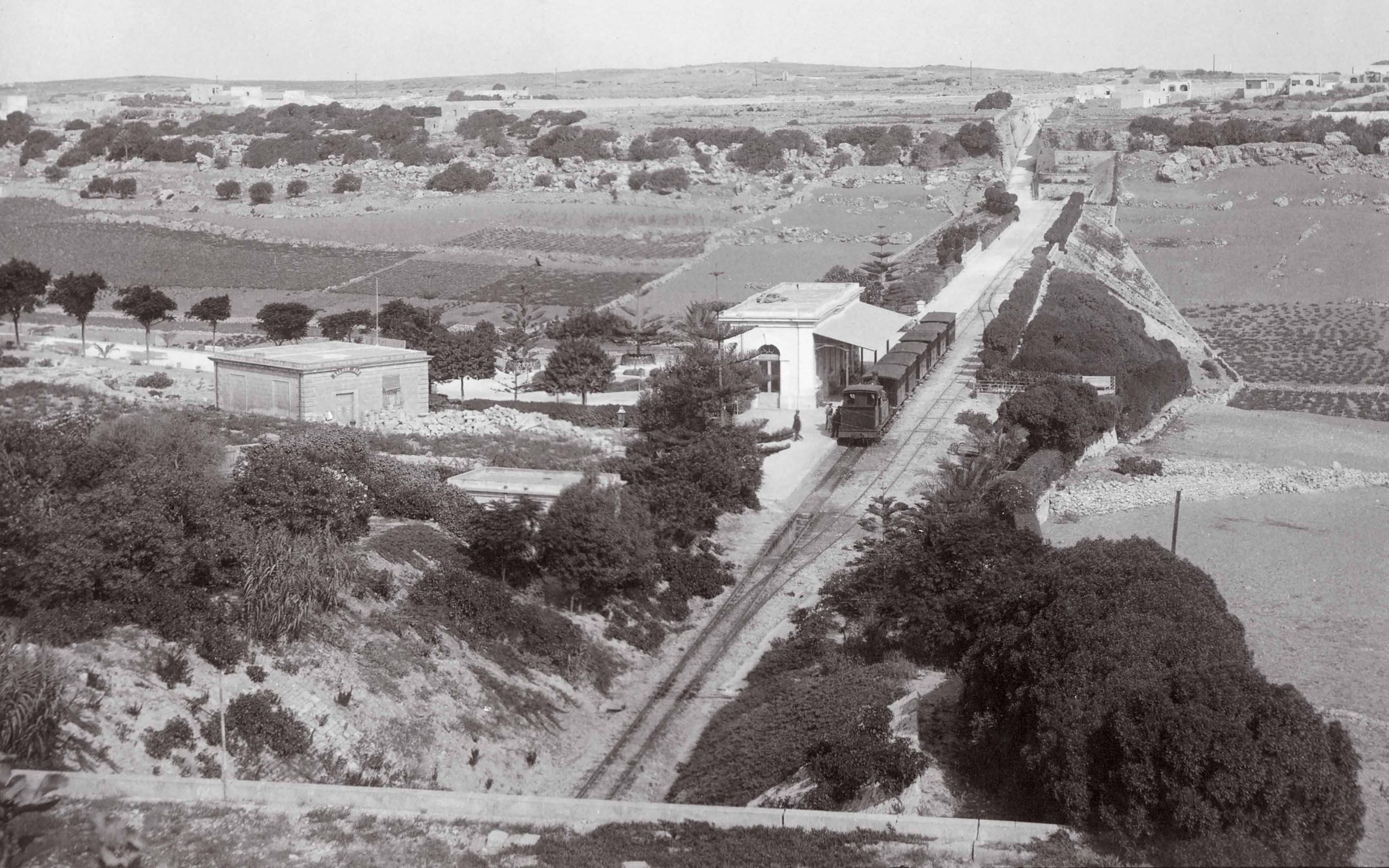

Located at the bottom of a long road from Rabat, dug specially to access it, the station was one of the prettiest:. On a line of such eccentricities, it was something of an idealised harmonious vision of what a station should be. Gardens lining the new road, formally and regimentally planted, gave it the impression of being approached by some grand processional way before the greenery opened out around a circular ornamental pond with eight bronze dolphin fountainheads spouting from the edge.

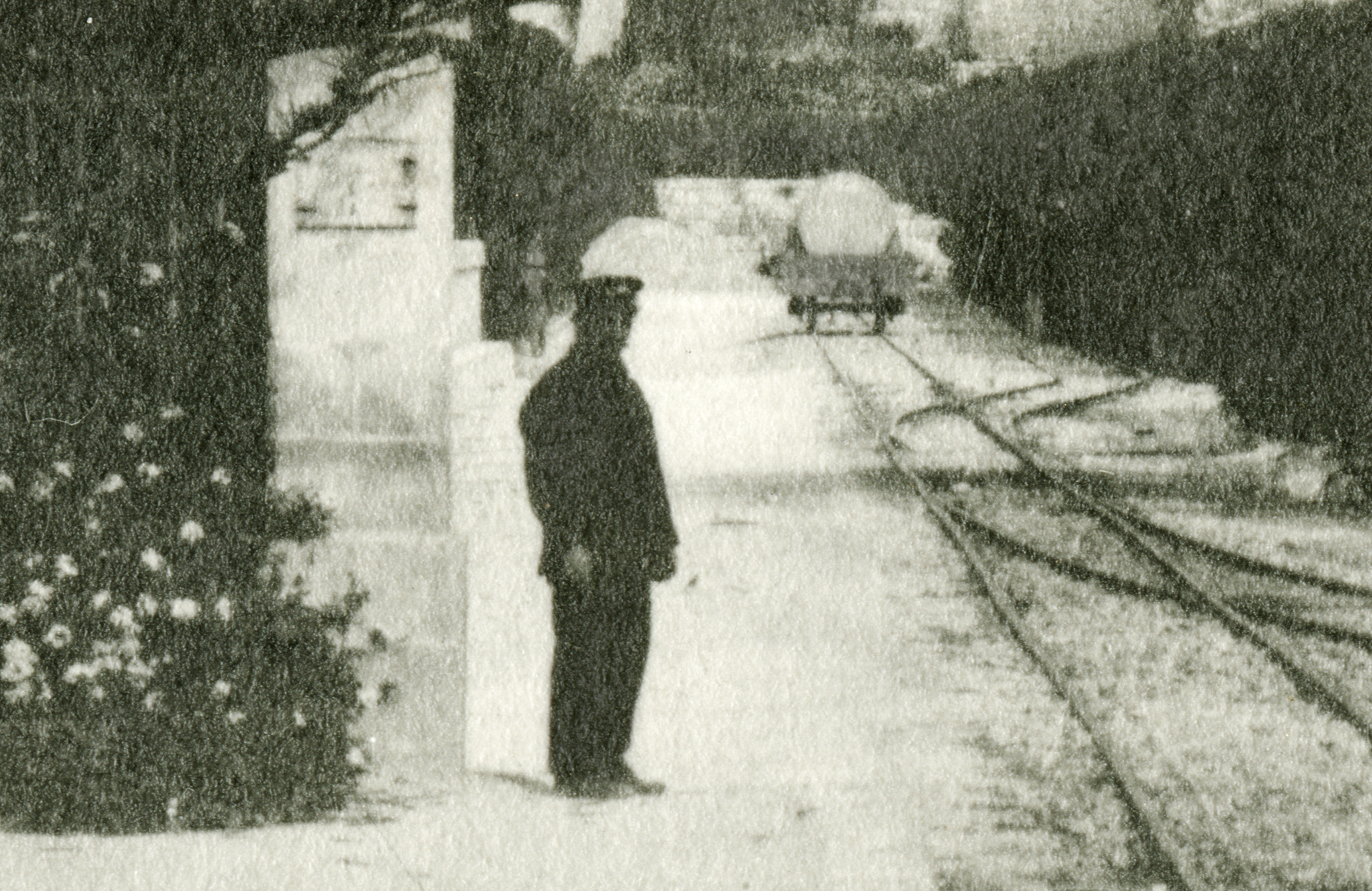

Standing immediately in front of the prospective passenger, the building itself had a strident architectural character; Tall, with six arched windows and a central arched doorway projecting forwards slightly with the station name painted on. The façade was framed by a deep cornice and shallow pilasters either end. The effect was further enlivened by the painting of the recessed bay around the windows in red ochre, making the entrance stand out. Either side, a regiment of stone piers linked by railings secured the platform from fare-dodgers.

Once through the booking hall passengers were treated to fine views down the valley and up to the city walls. A large canopy provided ample shade to enjoy the panorama and the gardens planted both sides of the line. These were somewhat haphazardly arranged compared with those on the station approach, but included palms, Norfolk pines, oleander, and many flowers. One curious feature was the alternating pink and white oleander bushes, densely planted in regimented stripes up the face of the railway embankment. Hidden among the greenery, at a sensible distance from the main building and towards the tunnel mouth, were the station latrines.

Two other structures completed the station area. On a raised spot overlooking the railway was the Coronation Bar, not an official railway property but providing welcome refreshment for passengers and spectators alike. From the name, it’s reasonable to assume it opened in 1902, coinciding with the coronation of Edward VII and Queen Alexandra that year. The other structure is more perplexing. Beneath the level of the railway line and opposite the station building, it was built into the embankment so that its far end projected outwards above it. It was aligned differently to the line and is known to have existed before the track formation was built up behind it. When the railway opened, the half-sunken building was accessed by steps down, and the flat roof converted into a look-out point with railings and benches arranged around its perimeter. Its use and origins are a mystery.

The track layout was simple. A line for the platform, a passing loop allowing engines to run around their trains for their return journey, and two sidings. One long siding stretched the length of the embankment to Mtarfa and was skirted by a road. Had mass troop movements taken place this would have allowed easy embarkation but it’s likely it was more frequently used for the extra trains and rollingstock needed for high days and holidays. The other siding was shorter, terminating on Għeriexem bridge. During the summer months, a metal drum mounted on a ballast truck was stored here for dispensation of water to irrigate farmers’ fields further down the line; a service from which the railway profited.

At the south end of the station was an inspection pit. This was dug beneath the track level and provided with steps to allow the underside of the locomotives to be checked. This mirrored a similar structure at Valletta.

As a later addition to the railway, Museum was the only major station not having been rebuilt after Government takeover. By the time the line closed only the gardens had changed, coming to maturity and almost threatening to engulf the tracks. Even after the removal of the rails the station was slow to change. By the 1960s the main building had become derelict and the tunnel given over to a mushroom farm. Fortunately a new use was found for the station, a restaurant, and saw the building restored.

Today, Museum remains well preserved despite more than ninety years having passed. The monumental Għeriexem bridge and embankment, tunnel, and station building are all now Scheduled as historic sites by the Maltese Government, ensuring their future protection for generations.

Previous Station