Hamrun

1 mile, 28 chains – Journey time 5 mins

Railway town

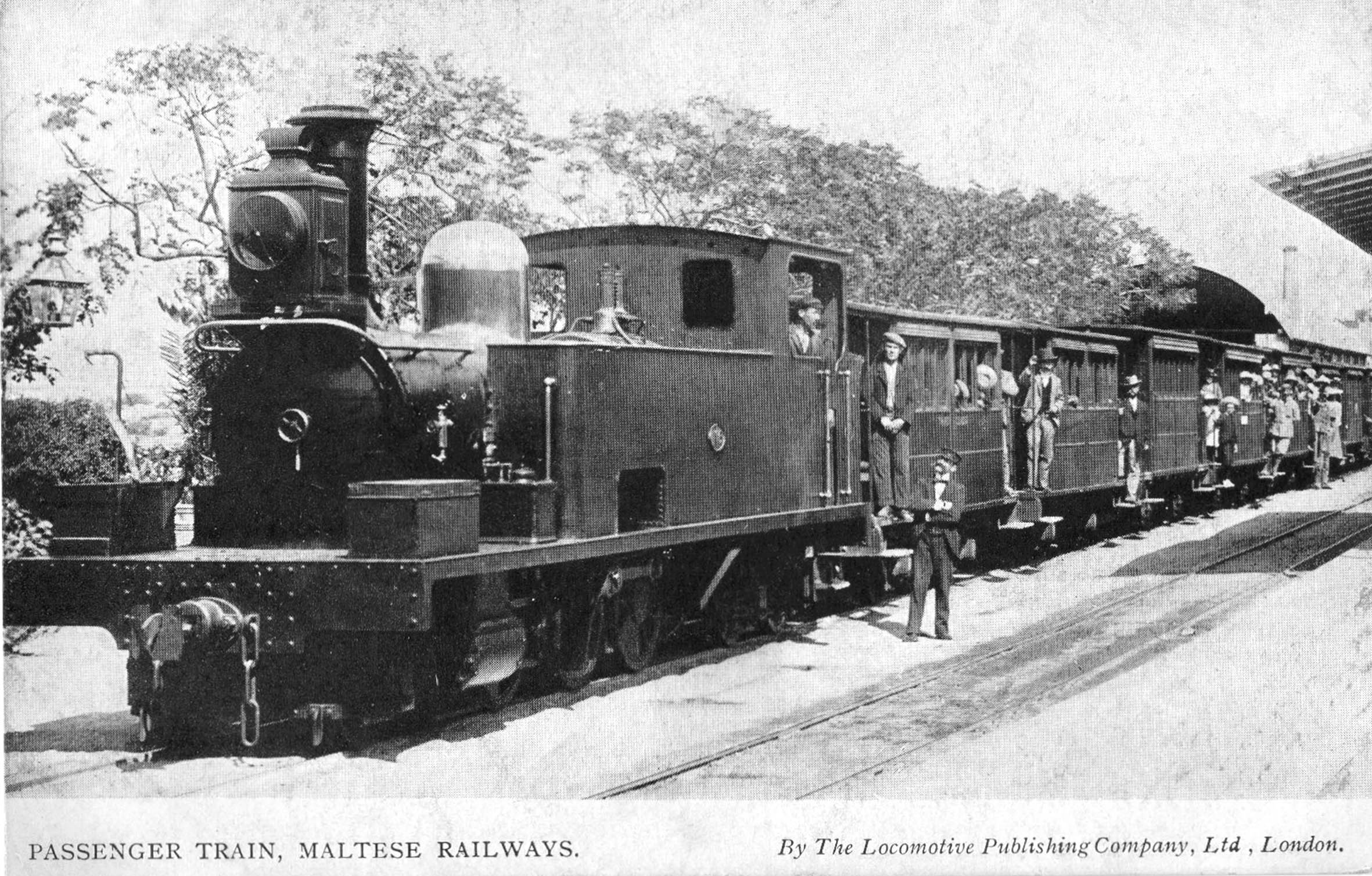

Even though Government ownership saw all major Malta Railway stations rebuilt in some way, Hamrun underwent the greatest transformation. Its position as the closest above-ground to the Valletta terminus made it the logical choice to base the engine and carriage sheds. From here engines could be prepared and trains made up to start their journey from the capital. However, the financial straits the railway company found itself during construction saw only the most basic provisions made on opening in 1883.

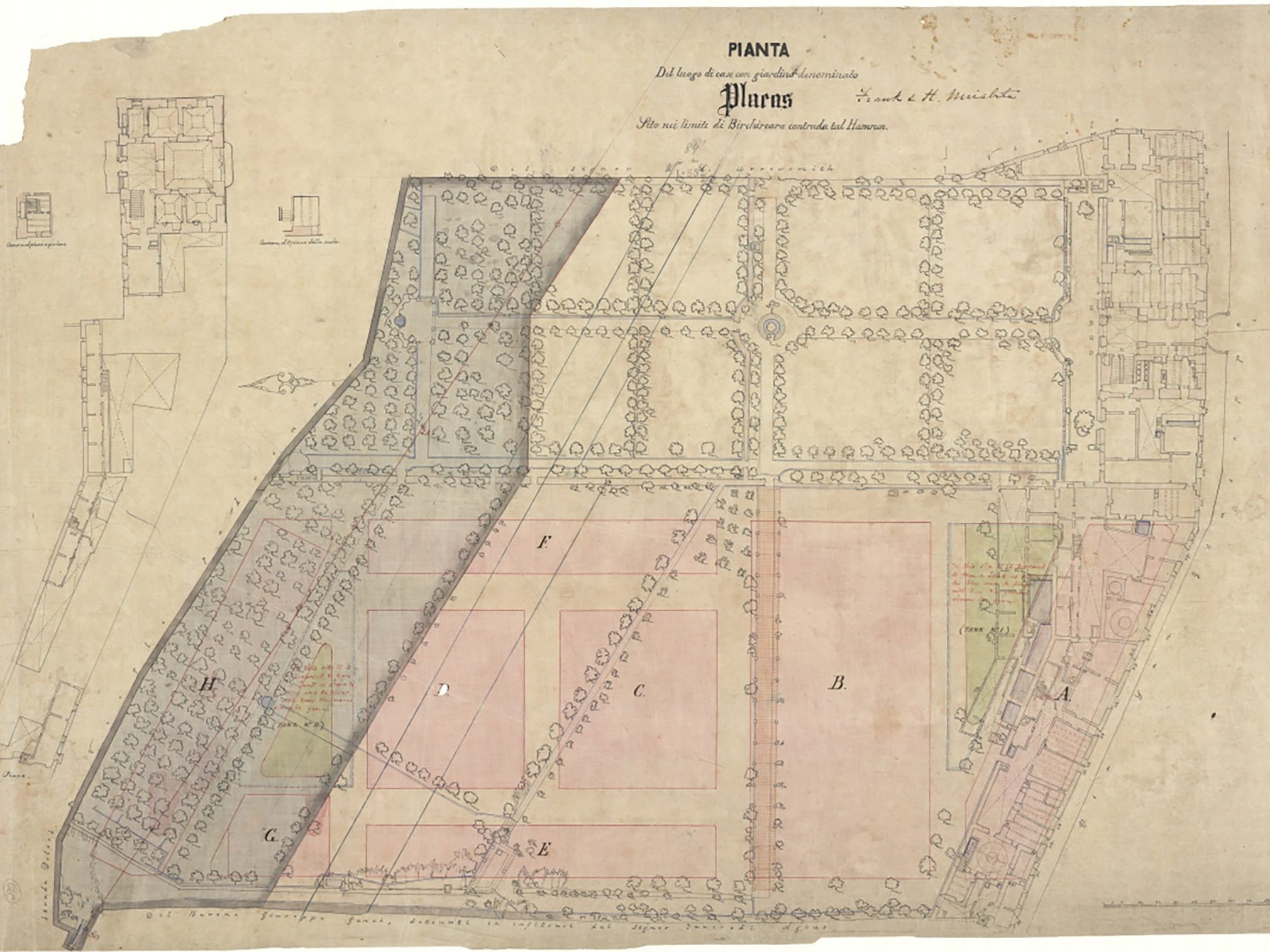

The site chosen for the new station was on a strip of land taken from the Ta Blacas (or Placas) estate, at the start of a wide bend where the track came closest to the town. As it happened, the mansion, gardens and land of Ta Blacas had just been acquired by the Government who cooperated with the railway for mutual benefit. Part of the once-beautiful gardens was transferred to the railway whilst much more was laid out for development. Perhaps seeing the potential of the coming railway they had model workers housing, Blacas Buildings, built on a new public square, Pjazza San Pawl. This would be of direct benefit to the railway in providing homes for its workers. A new Government School built between it and the station site would also become significant to the railway.

When it opened, Hamrun was classed as of the principal stations. Despite this, it was poorly appointed with a similar standard building design as Birkirkara and Notabile. This had only a station master’s office, a ticket clerk’s office, and a cramped booking hall with a bench; this was open to the platform through two arches. At this early stage it was possible to access the station from either road from Pjazza San Pawl, passengers arriving at a bleak open forecourt at back of the station building.

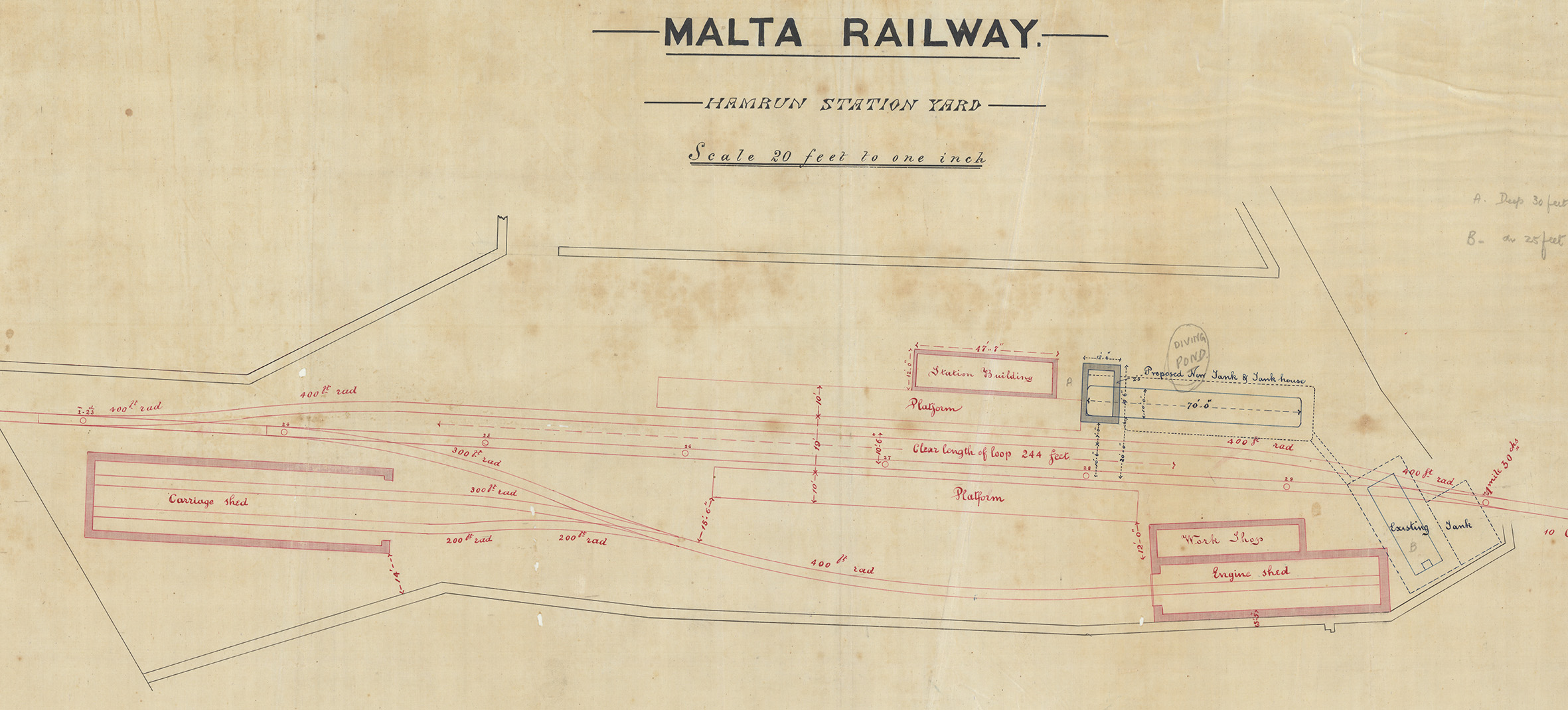

There were two tracks through the station, each with a low platform. The main line had a passing loop on the Hamrun side of the tracks, serving trains heading up the island. Valletta trains were boarded from the northern platform, accessed by walking across the line. The platforms were initially largely bare but for a water tower close to the station building to serve locomotives. The only other buildings in the station precinct being the company’s engines shed and carriage shed.

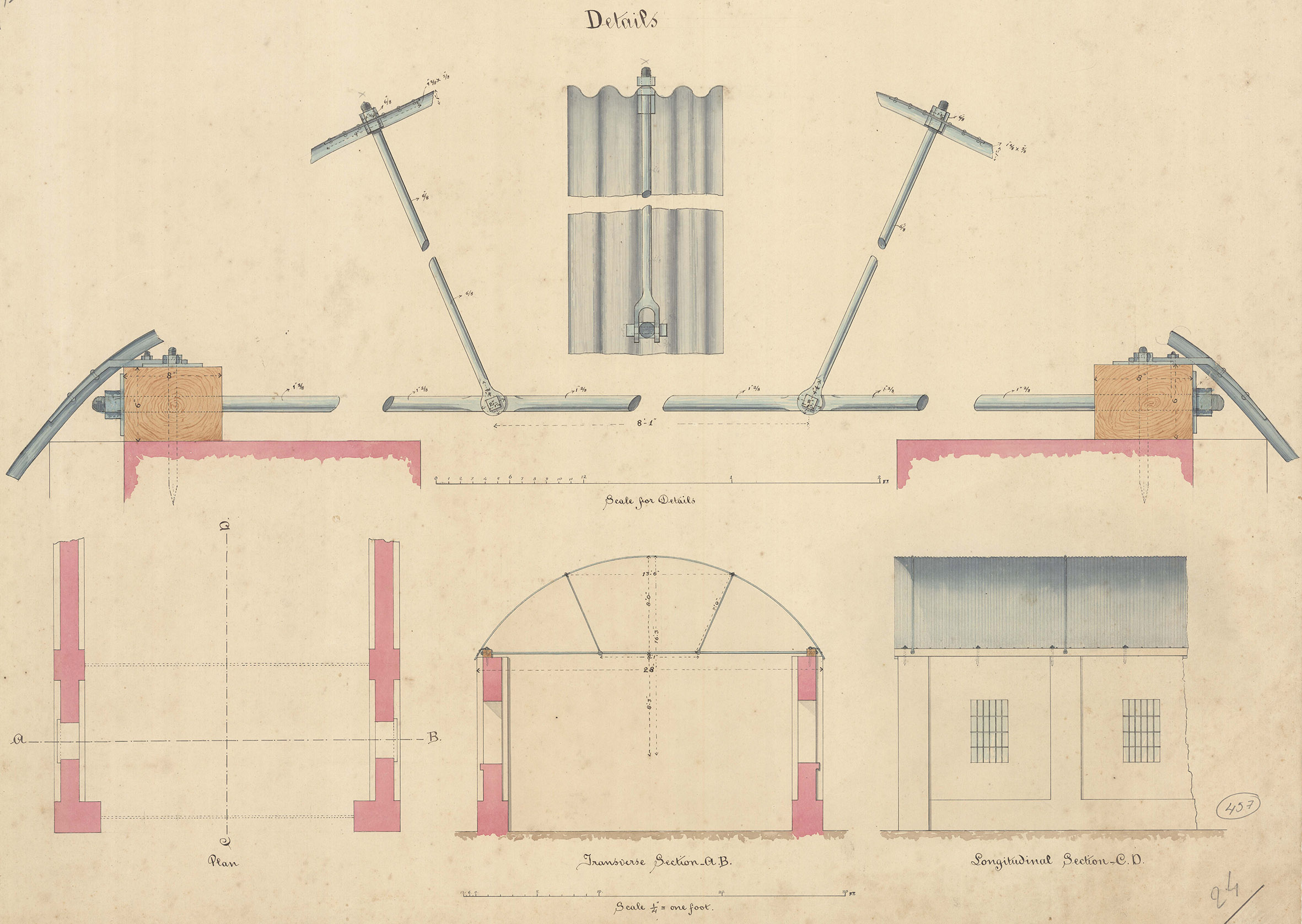

The designs of the largest of these buildings, the carriage shed, survive. Even at opening, it was too small to shelter all the new rollingstock. It was on the north east side of the station, parallel with the main line, and with two roads. It was simple in design, having stone walls to three sides, the fourth side open for carriage access. Windows lit the interior from both long sides and the roof was a lightweight steel frame structure covered in a curving galvanised corrugated iron roof.

Its partner, the engine shed, faced it across the yard and behind the furthermost platform. Similar in some respects, it had a pitched roof, probably also of steel fabrication. The shed was big enough only for the three locomotives purchased for the railway’s opening. This typified the original works on the whole line, that they would be just adequate enough, but with little capacity to support any expansion or development.

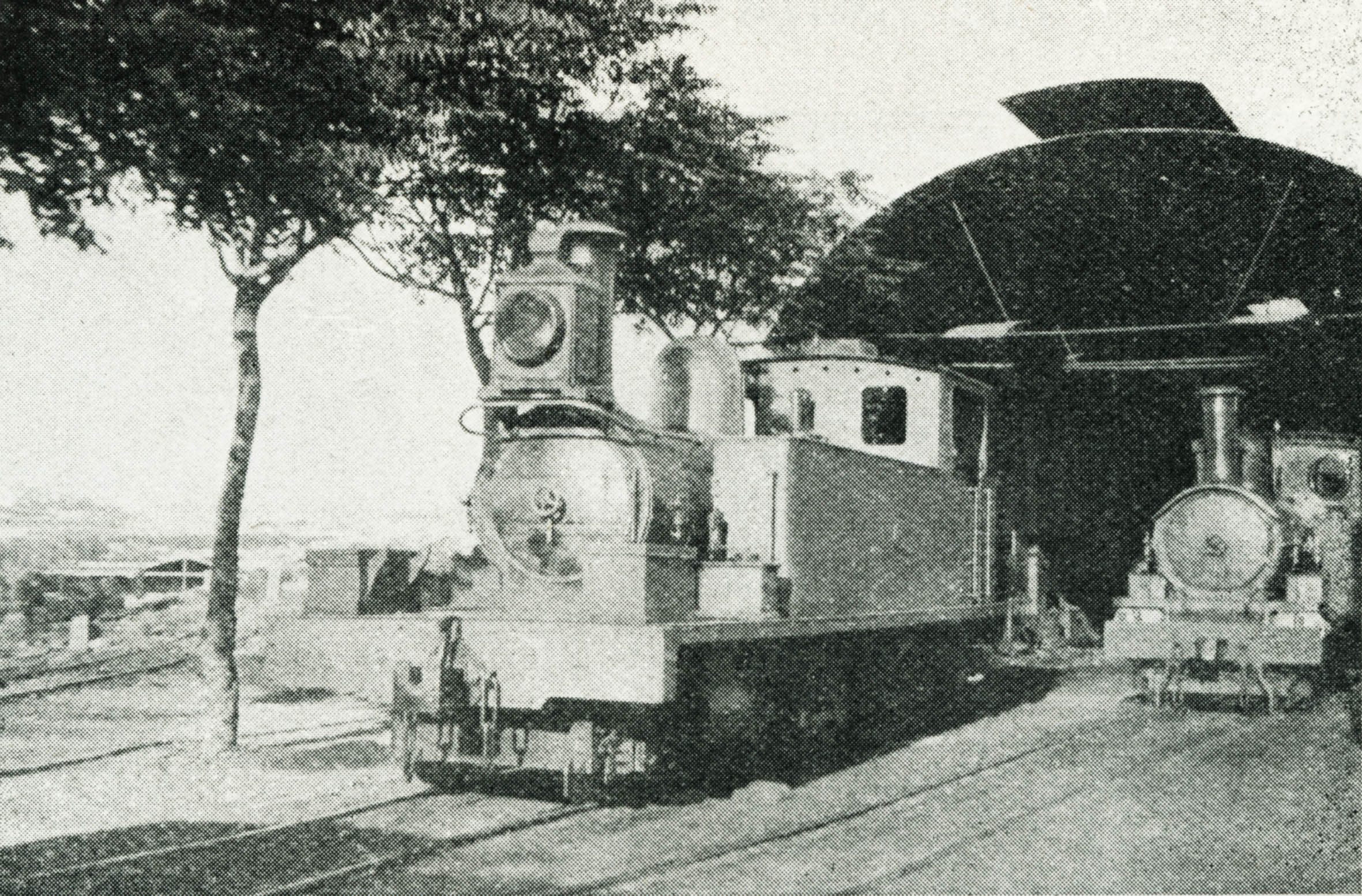

The lack of proper facilities to maintain locomotives or track was matched by a lack of expertise. By the time the railway company became insolvent and the Government were poised to take over, three of its four engines were inoperable. The fact that the boilers of two of them had to be transported to the Royal Navy Dockyard for repair highlights the limitations of facilities at Hamrun and the inability to undertake even basic repairs.

For Government, revitalising Hamrun was essential in ensuring the future running of the railway. A new engine, No.5, arrived in 1892 to re-start services. At this time it’s likely that the original carriage shed began a new life as a second engine shed, the old one too small to accommodate all the locomotives. In the same year, under the management of Lorenzo Gatt, a list of ten urgent items was drawn up, seven of which related to works at Hamrun. They included the construction of new engine and carriage sheds, latrines, a new planning machine and portable forge, construction of a room near the gate of the station (probably as a ticket office), reconstruction of a retaining wall on the north side of the station yard, and drainage. Some of these items were still outstanding a year later.

At the same time, a new workshop was built occupying a large section of the station forecourt. This was begun with the hope it would become a training workshop and technical school to ensure a supply of well-educated young engineers to maintain the line. It took on its first five apprentices in 1895. It boasted an inspection pit and sufficient tools and equipment were acquired to allow the railway to look after itself.

A forge was added at the same time, allowing the casting of metal components for the railway and other Government departments. Professional staff were engaged, a foreman fitter, two boiler-makers, two carpenters, a blacksmith, moulder, saddler, electrician, metalsmiths, a painter and a storekeeper. At this stage the facilities were still small but would grow quickly.

Alongside the new workshop, parallel with the southern boundary of the station, was a replacement carriage shed, offsetting the loss of the old one to engine shed use and expanding on accommodation. The new shed was built on a series of long stone arcades with a flat concrete roof and entirely open to the front.

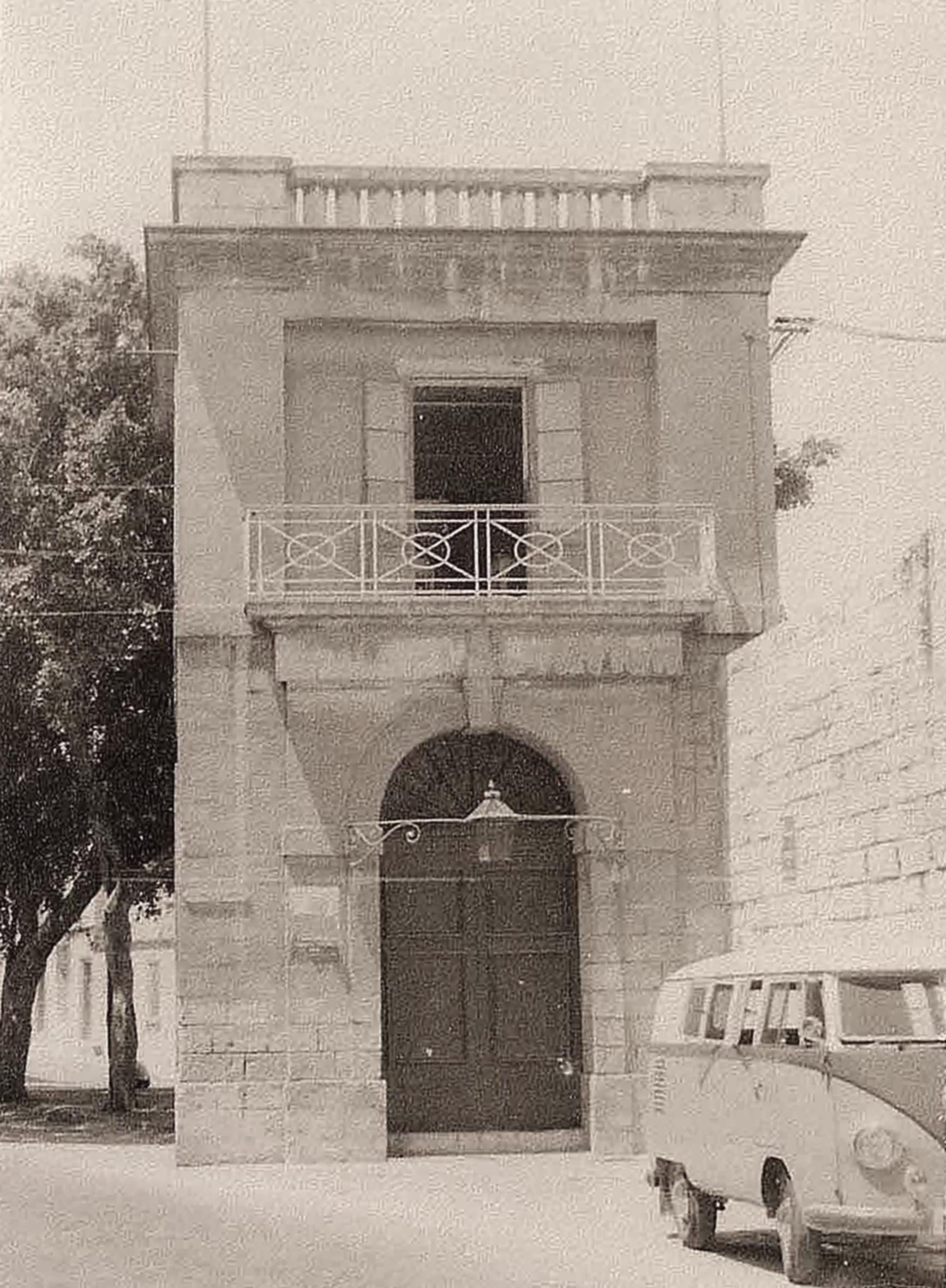

As part of the same phase of development, new boundary walls were built up around the station to protect revenue and a new ticket office was built with a commanding presence looking up the road to the High Street. This had a first-floor room above it, accessed by a precarious looking external stair and for use, it is believed, by the station master. On its roof a tall semaphore signal was erected to control access into the station.

In 1896 the maintenance workshops were due for extension as part of an ambitious plan by new manager Nicola Buhagiar. This though only appears to have happened after 1900 when a suitably grand and architecturally attractive entrance front was added. This may have been to the designs of self-taught Maltese architect Andrea Vassallo, who had worked on railway structures before 1887 and after this date was clerk of works in the Office of Public Works.

In his petition to be promoted to the role of surveyor in 1908 (a position he was well over-qualified for) he listed his accomplishments as including the “construction of the new workshop and the planting of machinery therein” and a new school at Hamrun that may have been the technical school buildings. There are some general similarities with other of his contemporary works, though other architects were also employed in that Government department, and Buhagiar himself also had architectural skills.

Buhagiar’s plan was to dramatically expand the station yard to the north, creating more than an astonishing four acres of new covered engine and carriage sheds. This would have required the demolition of the original carriage shed, reconfiguration of the track layout, and the addition of another station platform. Had it gone ahead it would have covered most of the area of the present Victor Tedesco Stadium.

However untenable Buhagiar’s grandiose plan was, he persisted with it, a revised plan being drawn-up in 1900, and a heavily reduced proposal in 1902; Surprisingly, works were actually begun on this last scheme. A large parcel of land was purchased to develop a first phase, to include a carriage shed and engine shed, each of two roads. The old carriage shed would be retained and the new facilities attached to them.

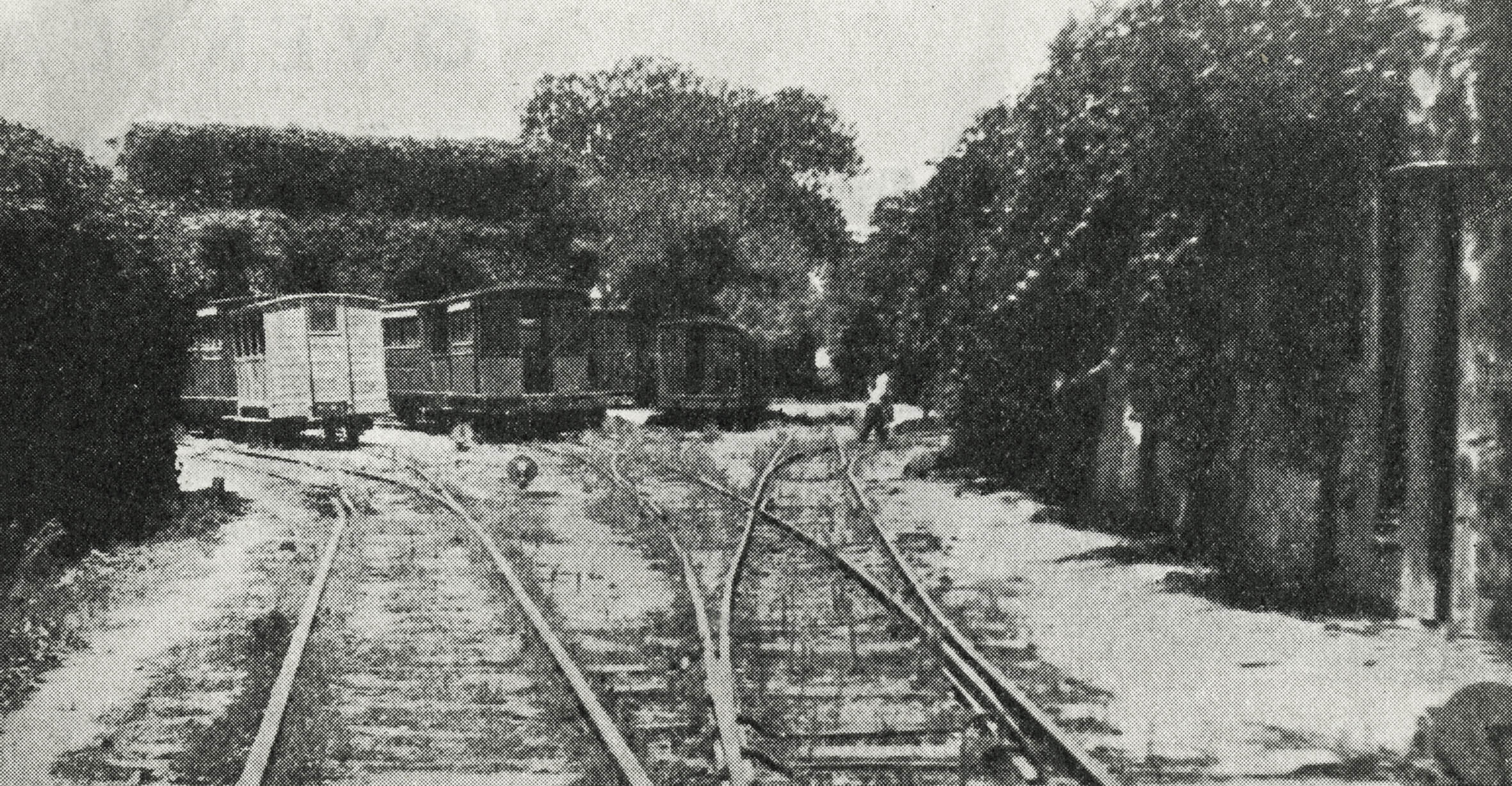

Beginning in 1903, a substantial retaining wall and terrace was thrown up along the north of the station yard, levelling the area by infilling a shallow valley there. Foundations were laid and preparations were made to construct the walls, and a first track was laid the length of the site, connecting with the existing sidings. And that’s where it ended. For whatever reason, probably the need to make urgent economies in running the railway, the scheme was abandoned. Works relating to the project appeared in three successive years of annual reports and absorbed more than £617 of the railway’s revenue. The siding seems to have seem most use for photo opportunities but would also have been helpful for coaling the locomotives that continued to be stabled in the old engine shed.

This plan also appears to have included a new building subsequently constructed against the northern boundary wall between the original sheds. It was used by the technical school, and In later life after the closure of the railway it was leased to Redifusion. Its original use is obscure; it had a central hallway with a larger room off either side and is suggested for use as dining room and apprentices use. It was a smart building with some architectural interest but was demolished in 1968.

Returning to the station building, the inadequate structure inaugurated with the railway survived into the 20th Century. It was extended, virtually rebuilt, before 1912. Scars in the building fabric illustrating this expansion were discovered during recent restorations.

The new building was taller, longer, and provided with a large canopy. It was similar to, but not matching, the stations at Attard, Birkirkara, and Notabile and may have been part of a systematic scheme of reconstruction of these stations around 1910. At Hamrun, the new building probably coincided with another extension to the maintenance workshops. From inhospitable and inadequate to a well-appointed with fully fledged engineering works, Hamrun was finally transformed.

Most likely under the influence of Buhagiar, gardens were planted soon after the railway came into Government ownership. Both platforms received new sheltering trees, flower beds, shrubs, and were graced by some of the urns cast in 1911 for station garden use.

An oval pond was created close to the station entrance and planted around with citrus trees; Long after the railway closed this was dug-out and a deep pool created, said to have been to test navy diving equipment.

Another feature was the line of deciduous trees planted close to the track outside the old carriage shed. Whether to provide shelter or purely ornamental, they were an odd addition to an active railway yard. By closure in 1931 Hamrun gave the impression of being in a jungle, the trees and plants now untamed and bougainvillea swamping the station premises.

Photos taken in 1934 show the state of Hamrun three years after the railway closed. They show redundant carriages littered across the tracks awaiting sale; there had been few takers for any of the rollingstock or locomotives when tenders were advertised in 1932. The yard was cleared and everything not allocated for retention was scrapped in 1937, after which part of the station premises was separated out and the milk factory built.

The technical school survived the railway, retaining relevance as an educational establishment and as a going concern until moving to Corradino Technical Institute at Paola in 1965. It kept at least two obsolete locomotives, No.1 and No.5, a carriage, and acquired one of the old tramcars as learning tools.

Gratifyingly, most of the station buildings survive with few losses. The original carriage shed was demolished, probably in 1937; the ticket office and room over it at the station entrance were lost to road widening in the 1960s along with the end bay of the original engine shed; The small building on the north of the station yard went after 1967; The engineering works survive in their entirety and the rest of the station buildings are in good hands under the care of the 1st Hamrun Scout Group.

Previous station / Next station