The Locomotives

The railway maintained a crowded stable of little engines

One of the curiosities of the Malta Railway was that it had more metre-gauge steam locomotives than miles of track for them to work. Despite their somewhat drab olive green livery, the distinct and familiar character of some of these engine become synonymous with the railway. From some short-sighted early purchases, to the receipt of some unfortunate disappointments, and finding eventual success, the story of these engines is told below.

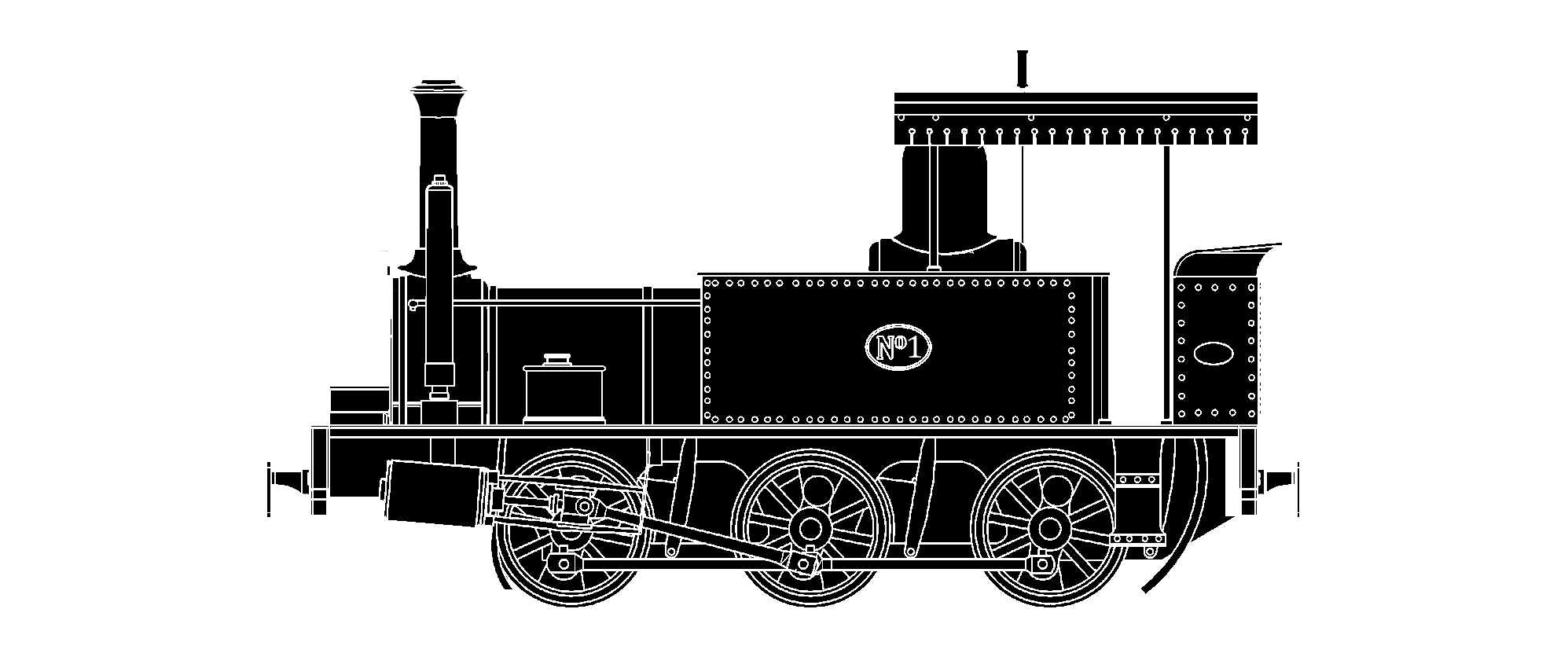

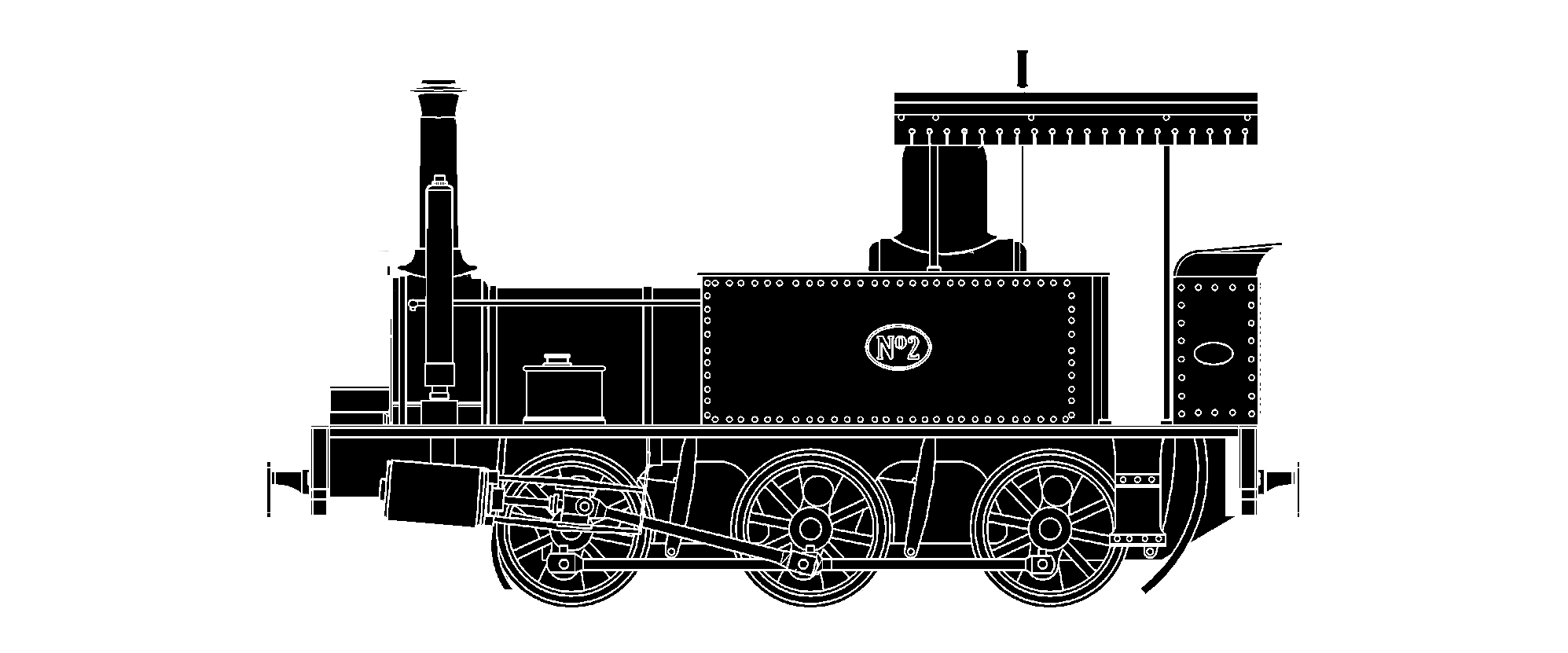

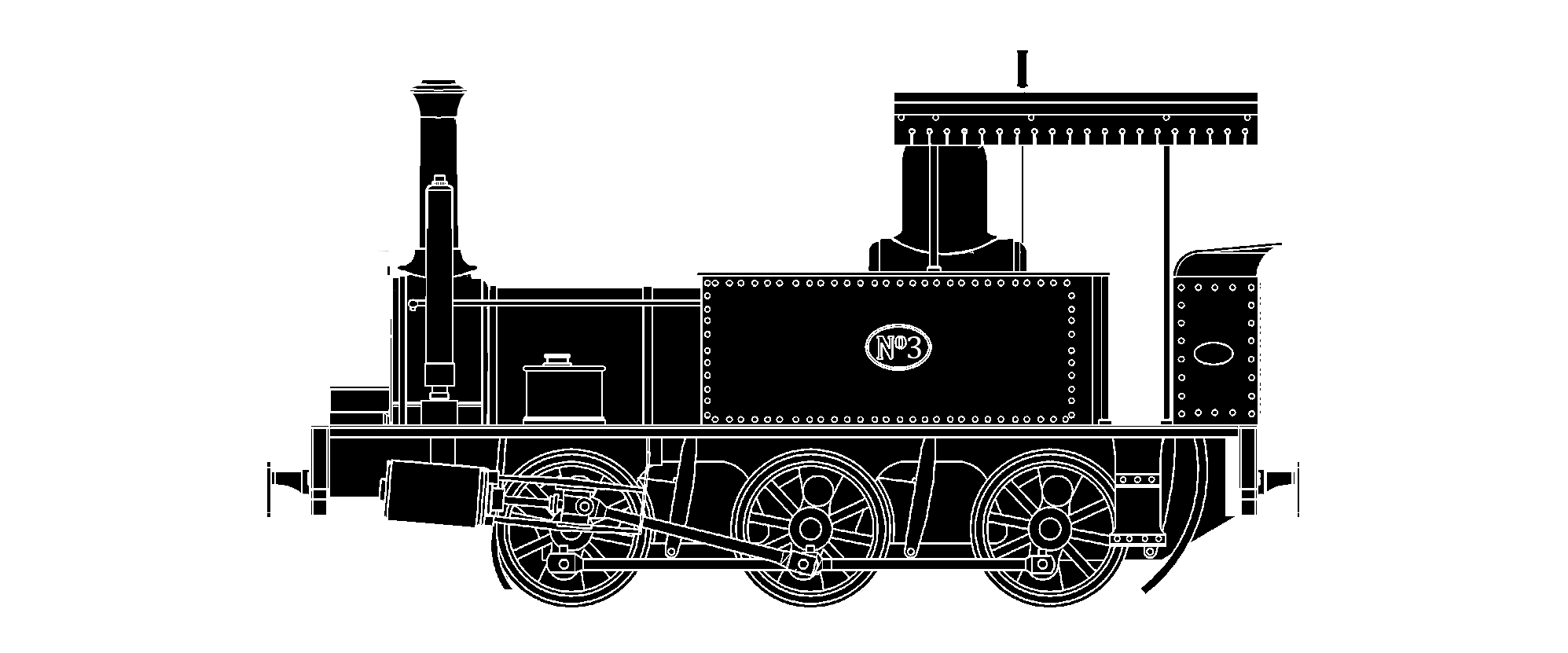

No.1-3: The Manning Wardle pioneers

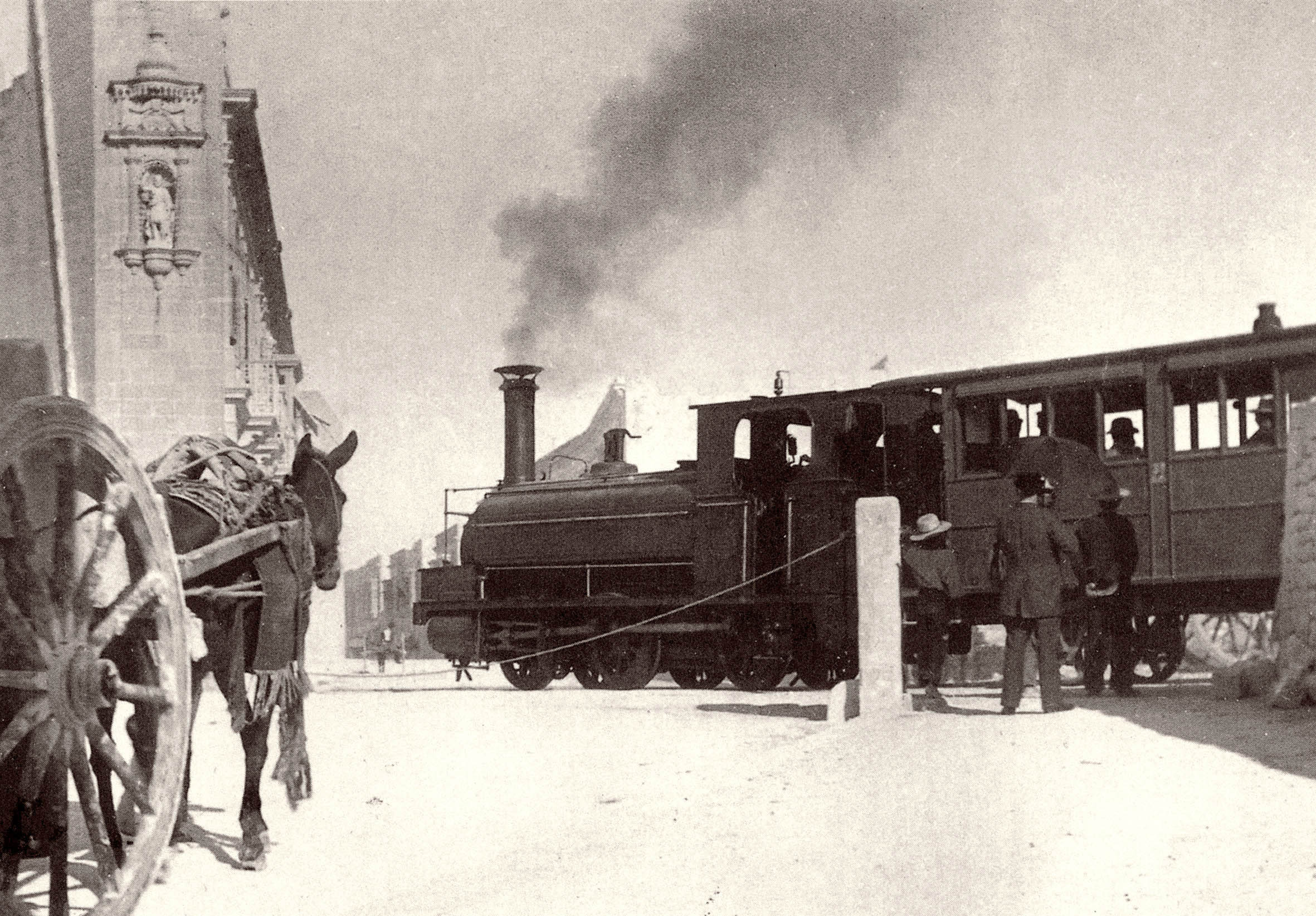

When the railway opened in 1883 it did so with three identical locomotives purchased from Manning Wardle & Co, Leeds, England. They were shipped to Malta individually, No.1 being sent in October 1882, with the others following in December the same year, and March 1883, a month after the inauguration of the line.

They were mechanically basic, an economic design with a simple 0-6-0 wheel arrangement, a short wheelbase, and only a flimsy canopy sheltering the driver and fireman from the elements. Whoever designed them clearly thought only of the hot sun and not the winds and Mediterranean storms that pass over the island!

The little engines were small “of but ‘pony’ power” and limited in their capacity to haul long trains up the steep gradients to Mdina. They were generally run with trains of four or five carriages, seriously limiting the line’s profitability. They were quickly overworked and were badly maintained. When the original company folded, they were all either broken down or in need of major repair work.

Although almost ruined by the original railway company they were repaired and returned to service under Government ownership, usually performing lighter duties and hauling off-peak services. They frequently worked the Birkirkara-Valletta shuttle trains that didn’t traverse the more challenging gradients towards Mtarfa, but also took short trains out that far and back during quieter midday periods.

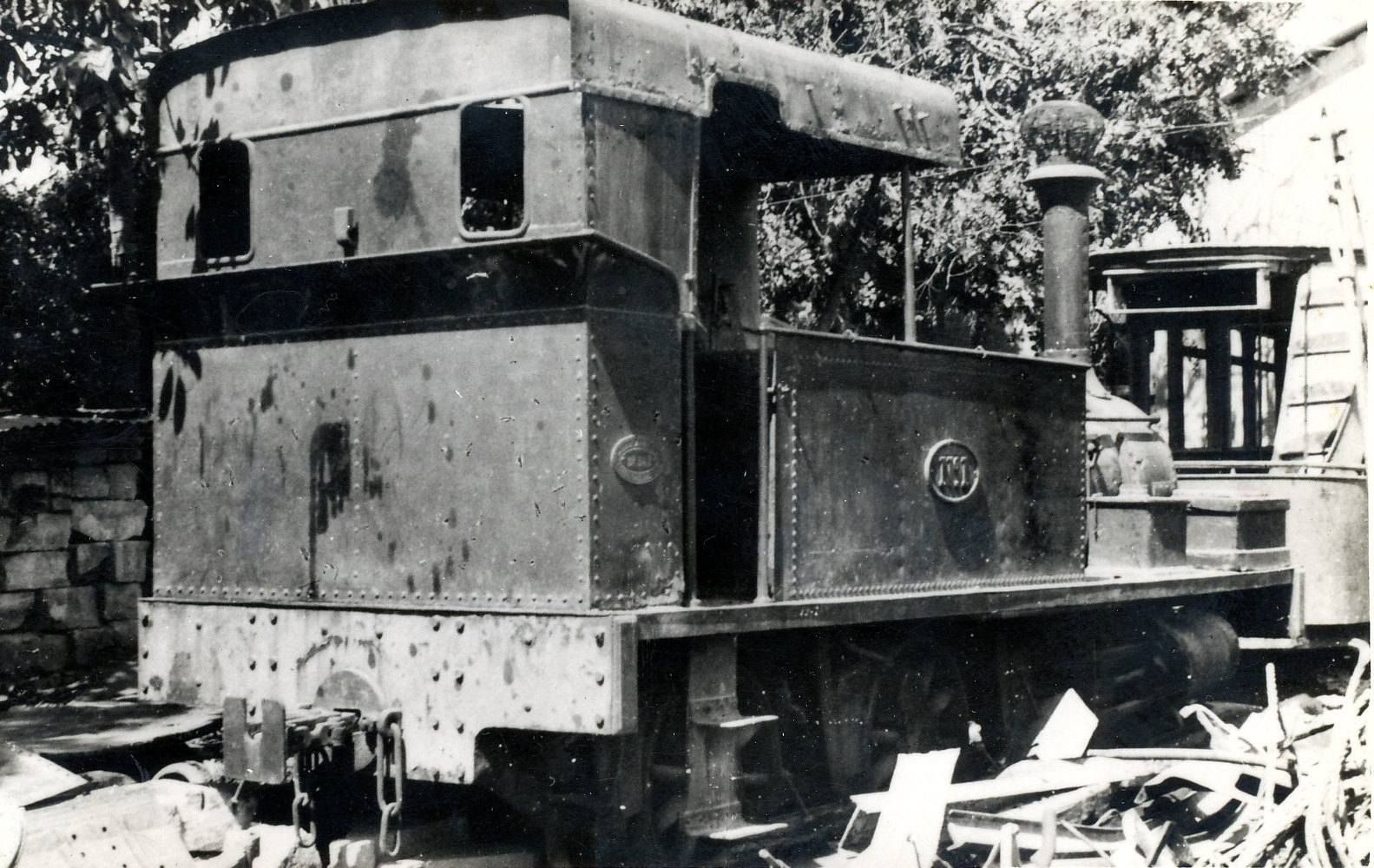

They served the line loyally and were very successful. No.3 was eventually retired by 1927, providing spare parts for the other two of the same class until the final closure of the line. No. 2 worked the entire 48 years the railway existed but it was the original engine, No.1, that was retained by the technical school after 1931. It was used for teaching purposes, eventually being evicted from its original shed and last photographed outside in derelict condition in 1945. Having survived scrapping and WWII it’s sad that the engine must have been dismantled soon after, now lost to posterity.

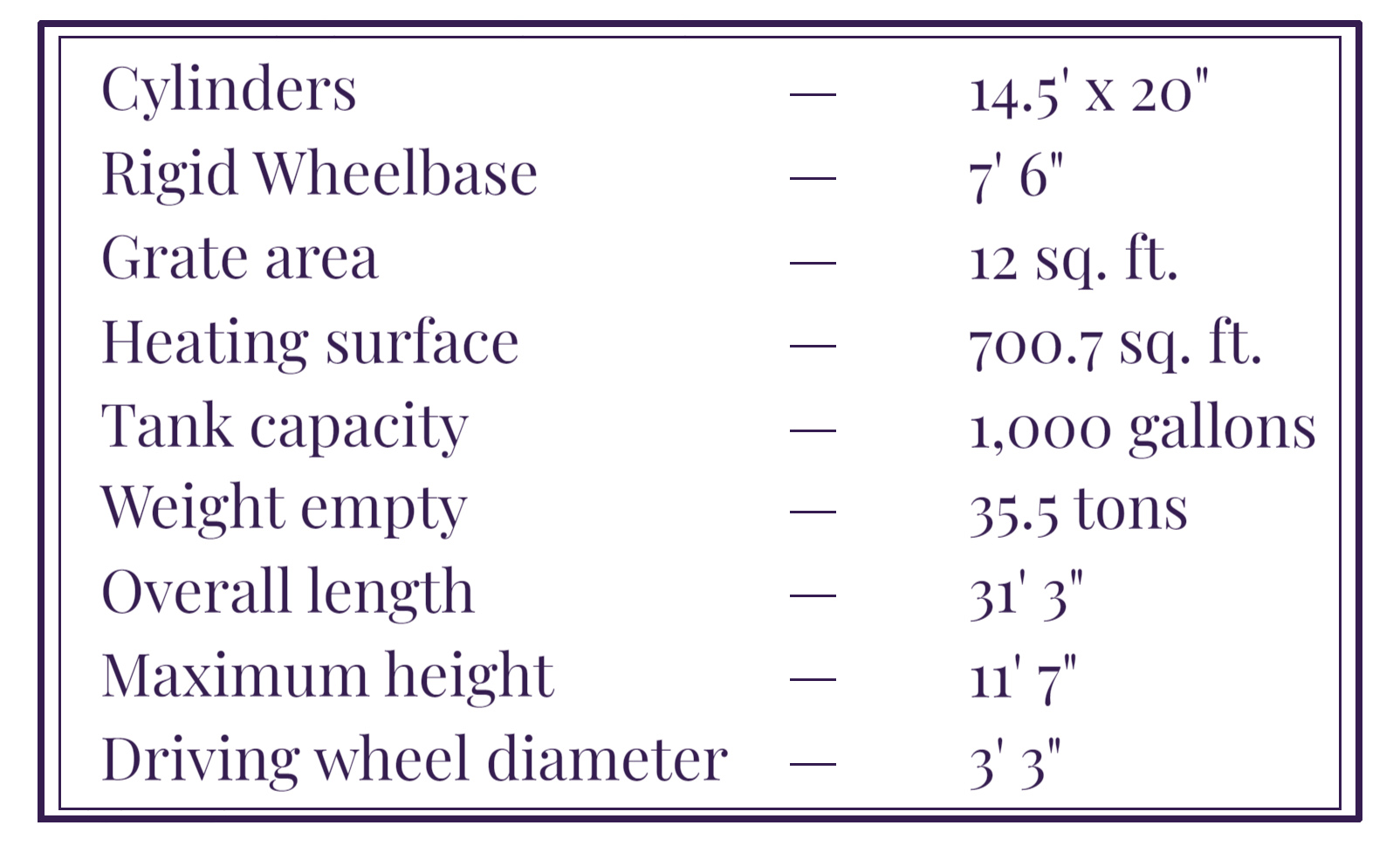

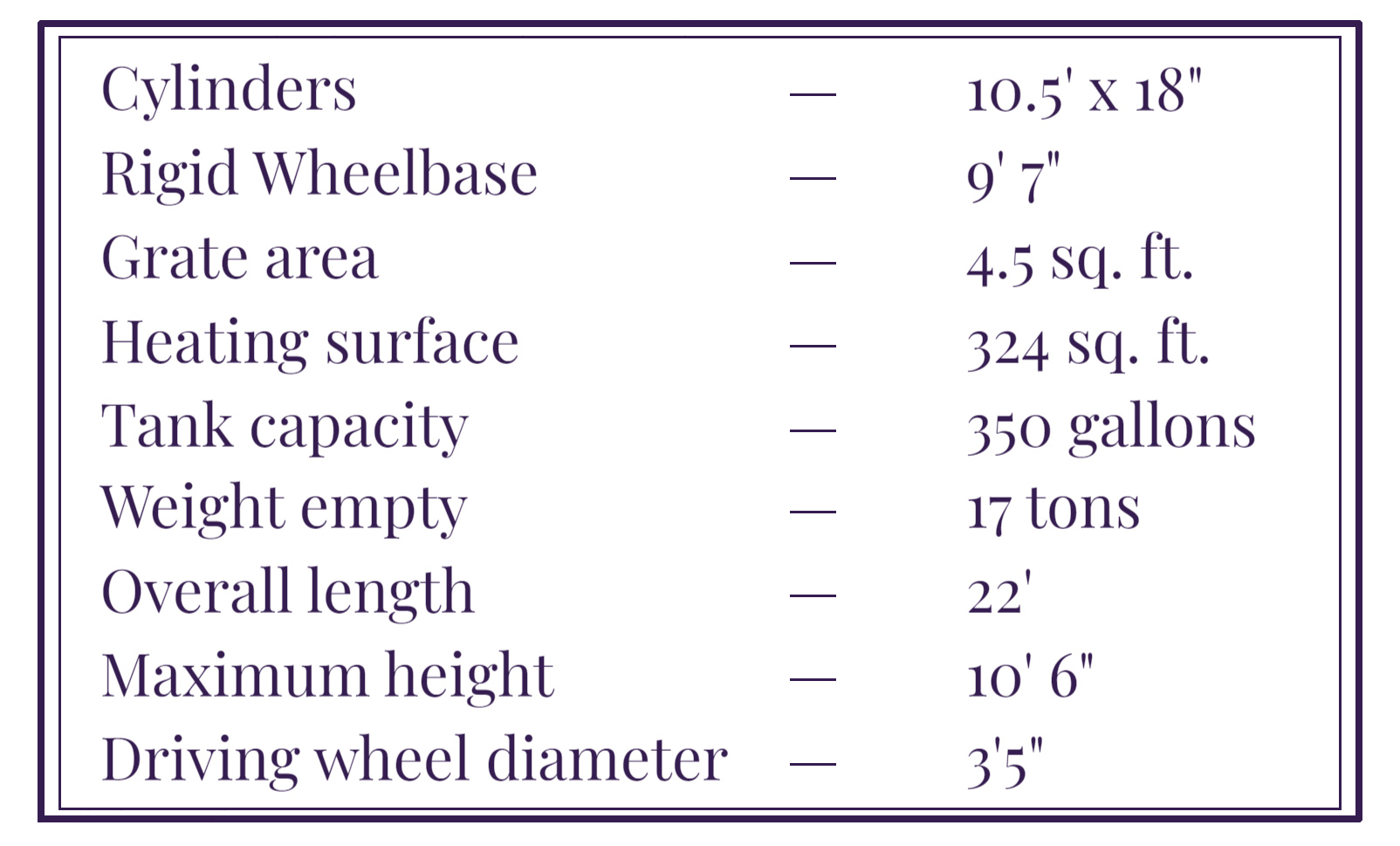

Statistics

Locomotives No. 1-3

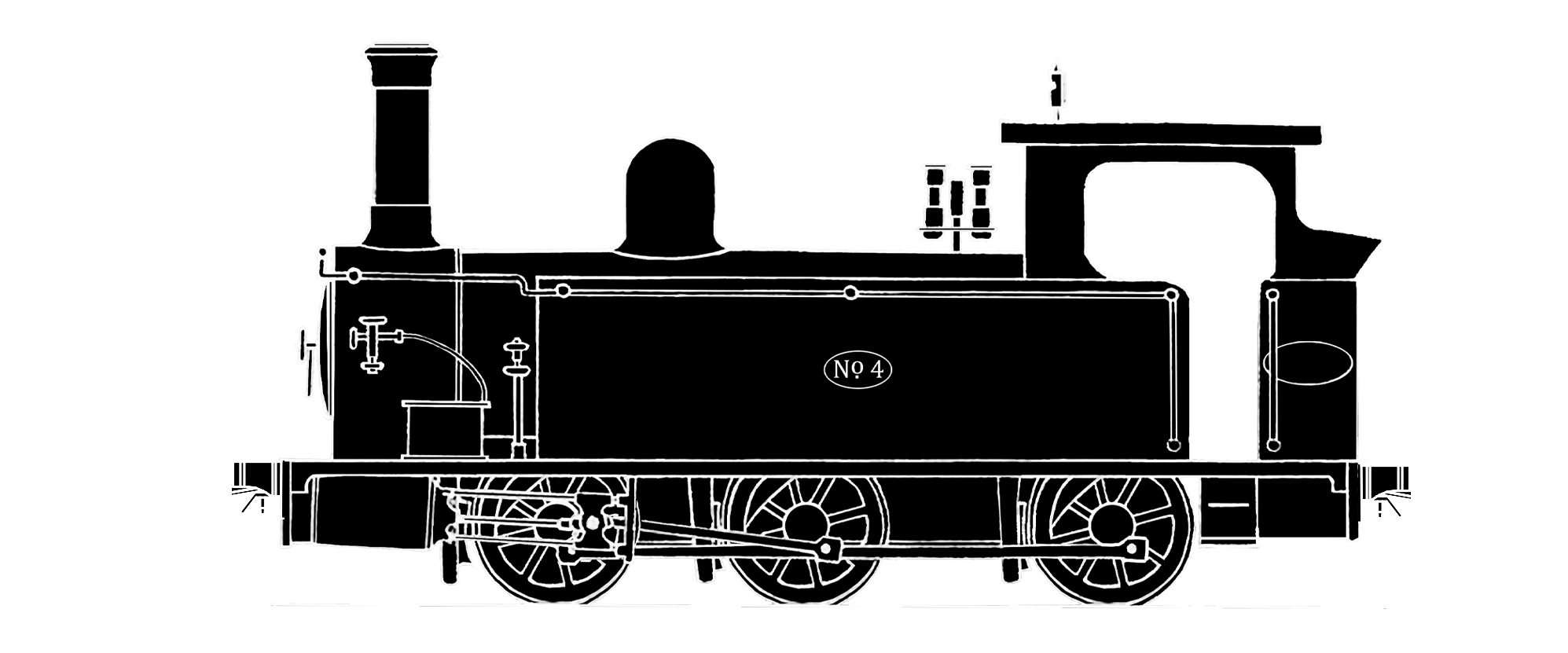

No.4: A faithful servant

No.4 became a popular and reliable engine, serving until the closure of the railway in 1931. Purchased two years after opening, it was much more powerful than its predecessors, an early recognition that the first locomotives were somewhat inadequate in maintaining services. It was the only engine bought from Black Hawthorn & Co of Gateshead and was of distinctly different appearance when it arrived in 1885. It was built with a saddle tank over the boiler rather than side tanks. It’s short wheelbase was dictated by the size of the sector plates then in use at either end of the railway to switch tracks, and the limitations of the lightweight rails then used for trackwork.

Although proving a good engine, the tank made the engine top-heavy and unsteady, leading to heavy wear of wheel bearings. When it came into Government ownership the decision was taken to rebuild it. This was one of the first major projects undertaken in the railway’s own new workshops in Hamrun and stands as testament to the skill and capacity of the engineering works. Modifications were made to the cab and coal bunker, a steam dome added, and side tanks introduced, giving the locomotive a more conventional outline. Before rebuilding it was the only engine that ever faced Valletta rather than Mdina. This was reversed afterwards, possibly to improve steaming.

Although the rebuild was ambitious it didn’t fully resolve the problems being variously christened “Il-Franciza” (after the Can Can dance), “the Gnome”, and “The Duck” after its perpetual waddling and rocking.

No.4 was photographed regularly out and about in service, often with reasonably long trains of at least seven carriages even on the gradients beyond Birkirkara. It was one of the last engines still available in working order in the last years of the line, though had reduced capacity and reliability.

Statistics

Locomotive No. 4

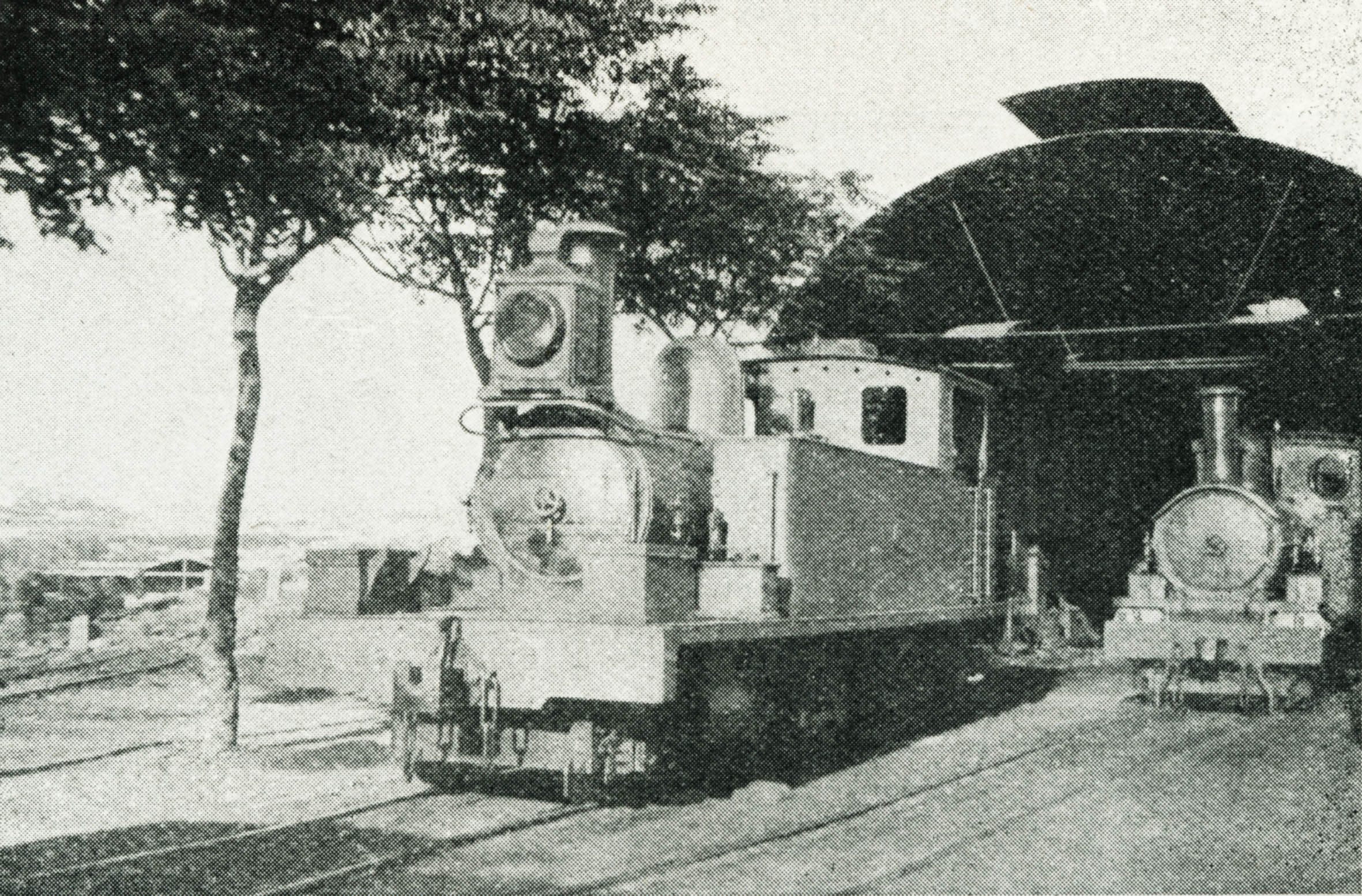

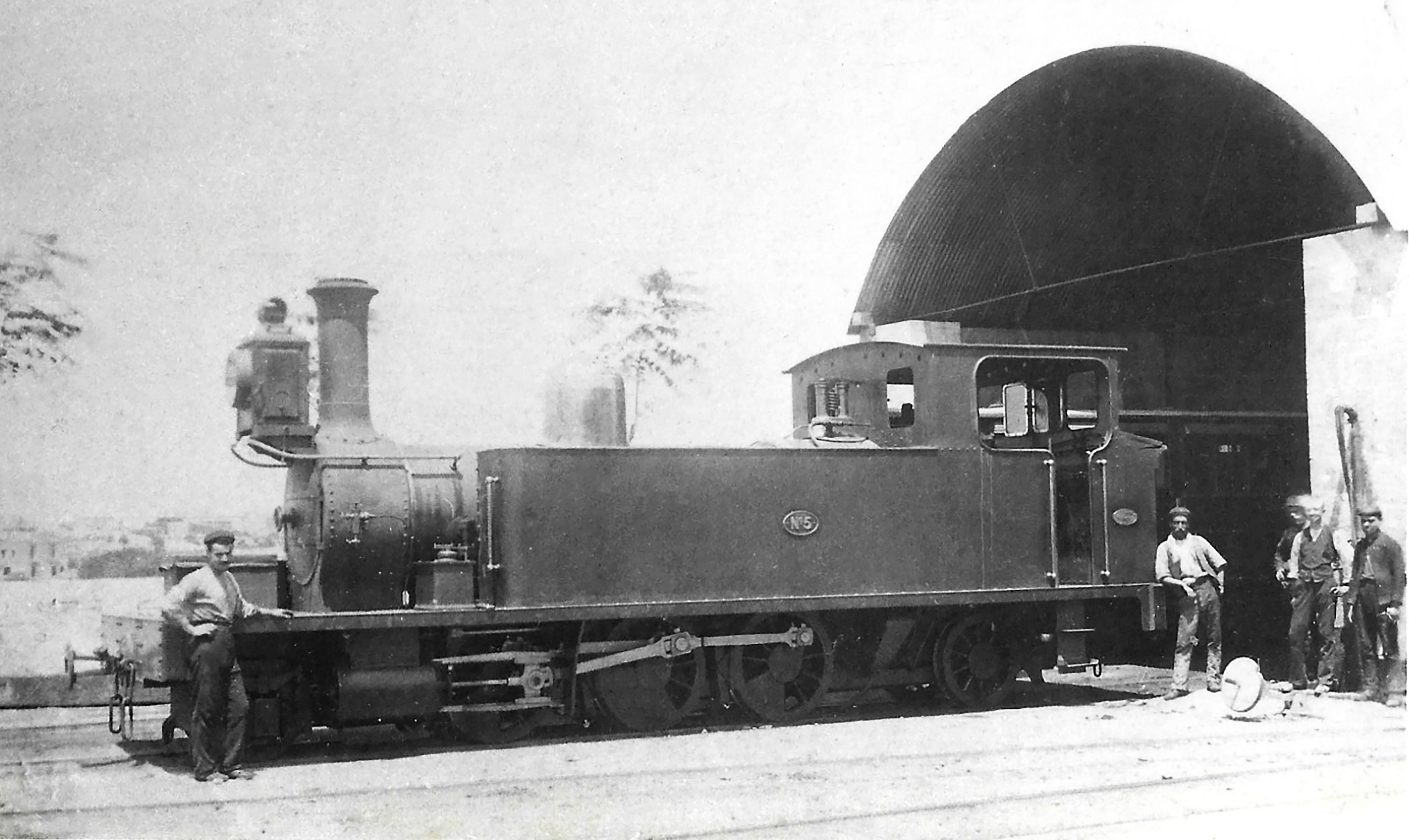

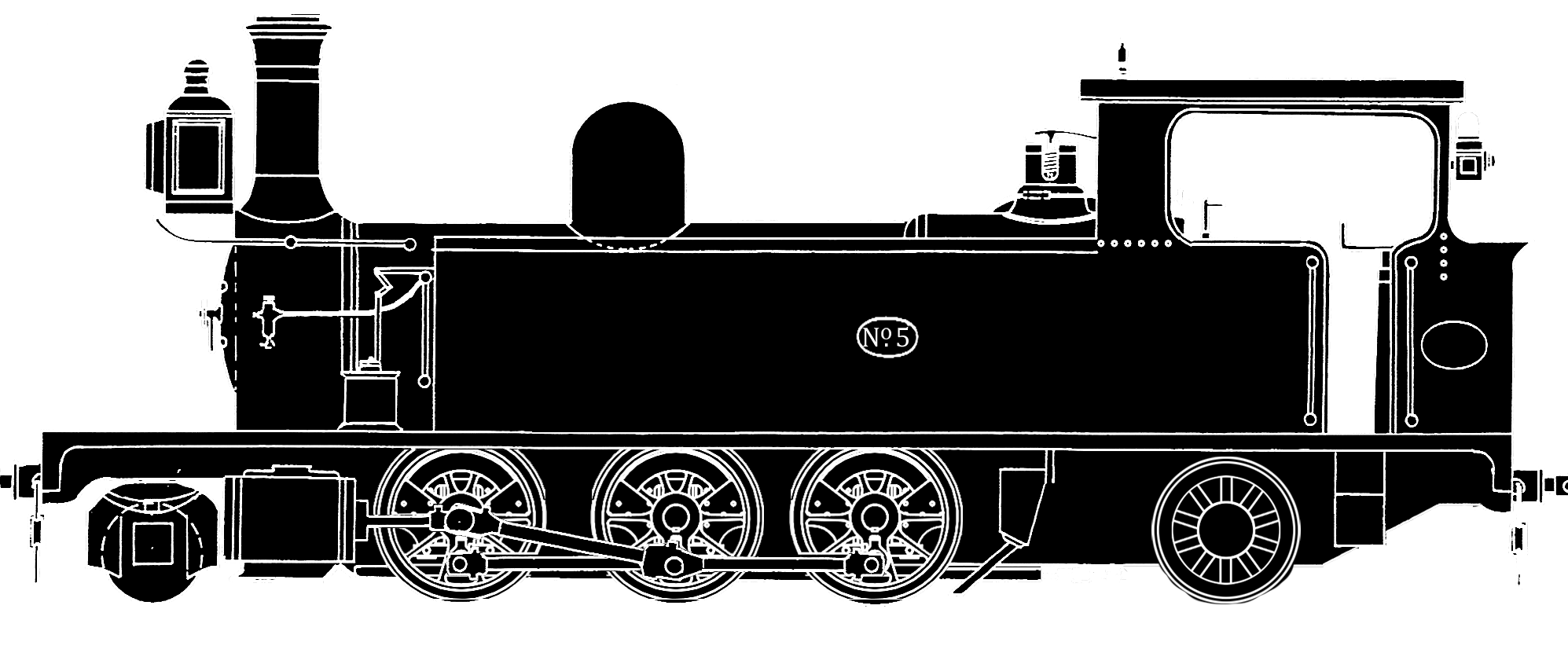

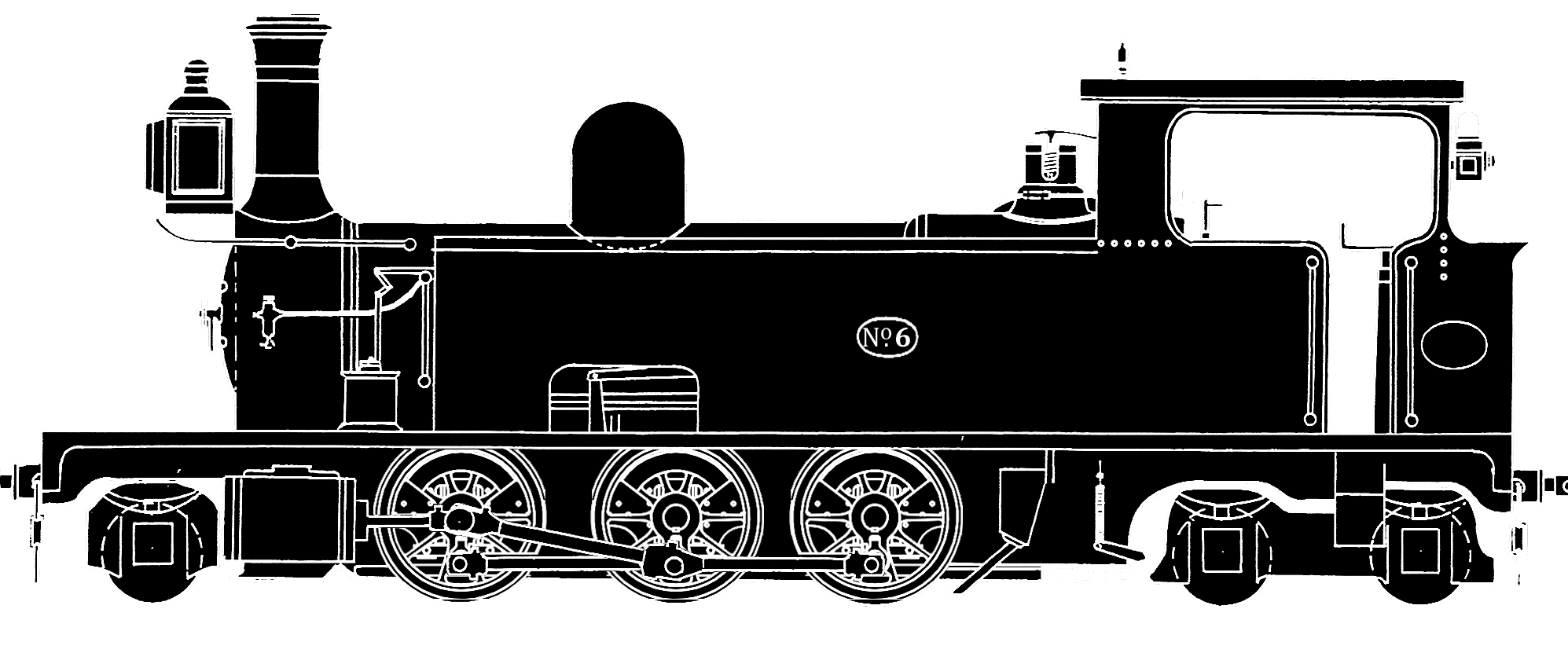

No.5 & 6: A failed experiment

These engines were purchased after Government takeover of the railway in 1891 under the management of Lorenzo Gatt, his aspiration being a regular half-hourly service along the line. The reopening of the line was postponed until No.5 could be delivered by Manning Wardle in December, before services recommenced early in 1892. The new engines were a dramatic change from the originals, being significantly more powerful and large. They were unusual in having large American-style lamps mounted over the smokebox; a feature they retained throughout their life.

It was hoped that more powerful engines would increase capacity and efficiency of trains, but it was quickly found that the new arrivals consumed fuel at an accelerated rate and were expensive to run. This, combined with the damage caused to the track by the increased weight and length, and unbalanced load distribution, created a new headache for the railway.

Modifications were ordered before the delivery of No.6 to try and address these problems; a separate Bissell truck replaced the rigid rear wheels and an access opening created in the side tanks. Modifications were also made to No.5 to match her later sister. These changes improved the performance but didn’t entirely resolve the matter.

Despite being much more powerful, No.5 and 6 spent most of their time relegated to the shed as relief engines, leaving the original four locomotives to run the majority of regular services before new Beyer Peacock engines began arriving. No.6 was last used in 1914 and her sister in 1920. Seen rarely after, they were maintained in working order, brought out only occasionally for visiting photographers or used by the technical school for training. By the time the line closed in 1931, neither engine was functional. It was unusual then, that No.5 was retained by the school for teaching purposes. It may have survived as late as 1945 when No.1, also saved, was still idling in the Hamrun yard.

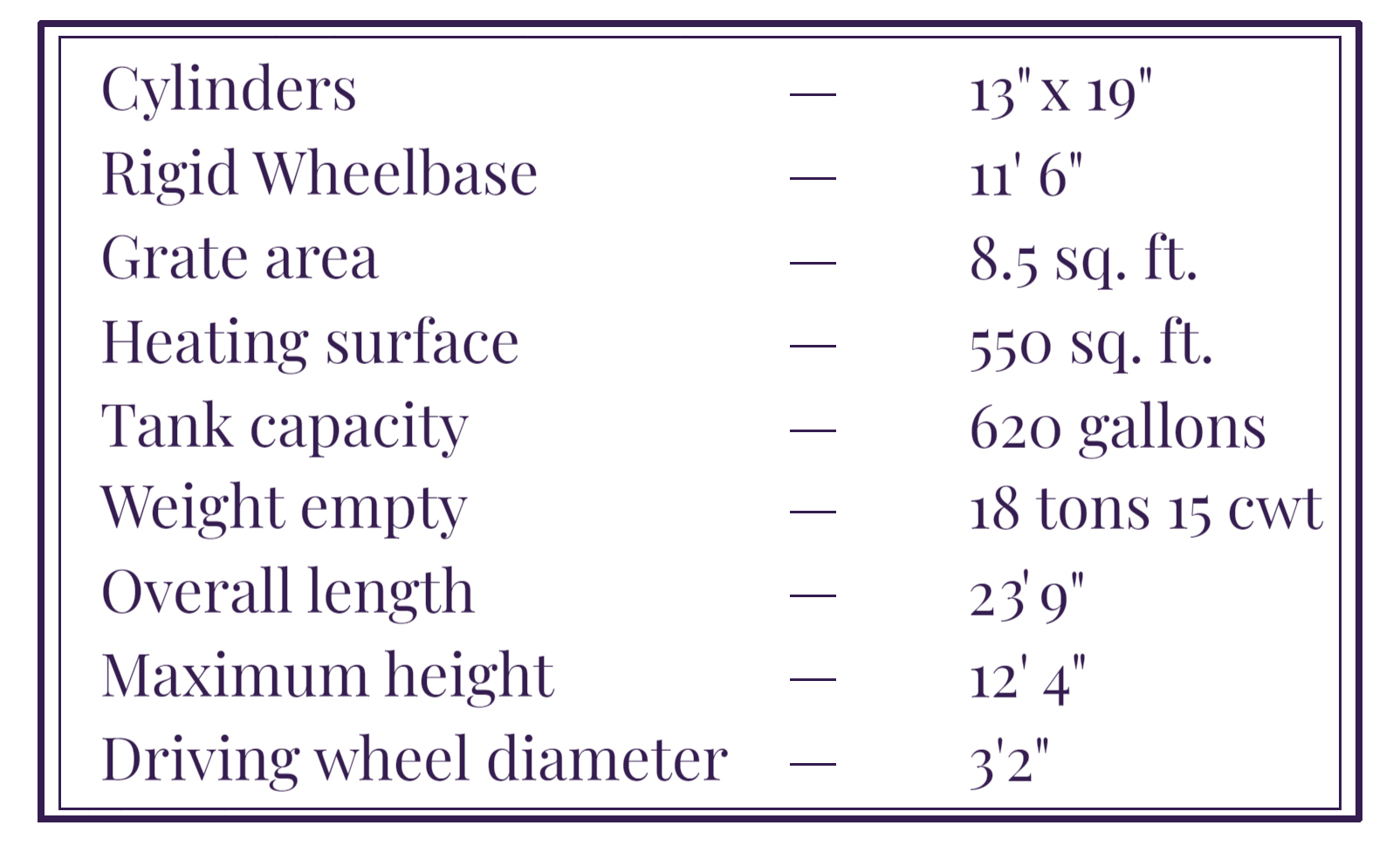

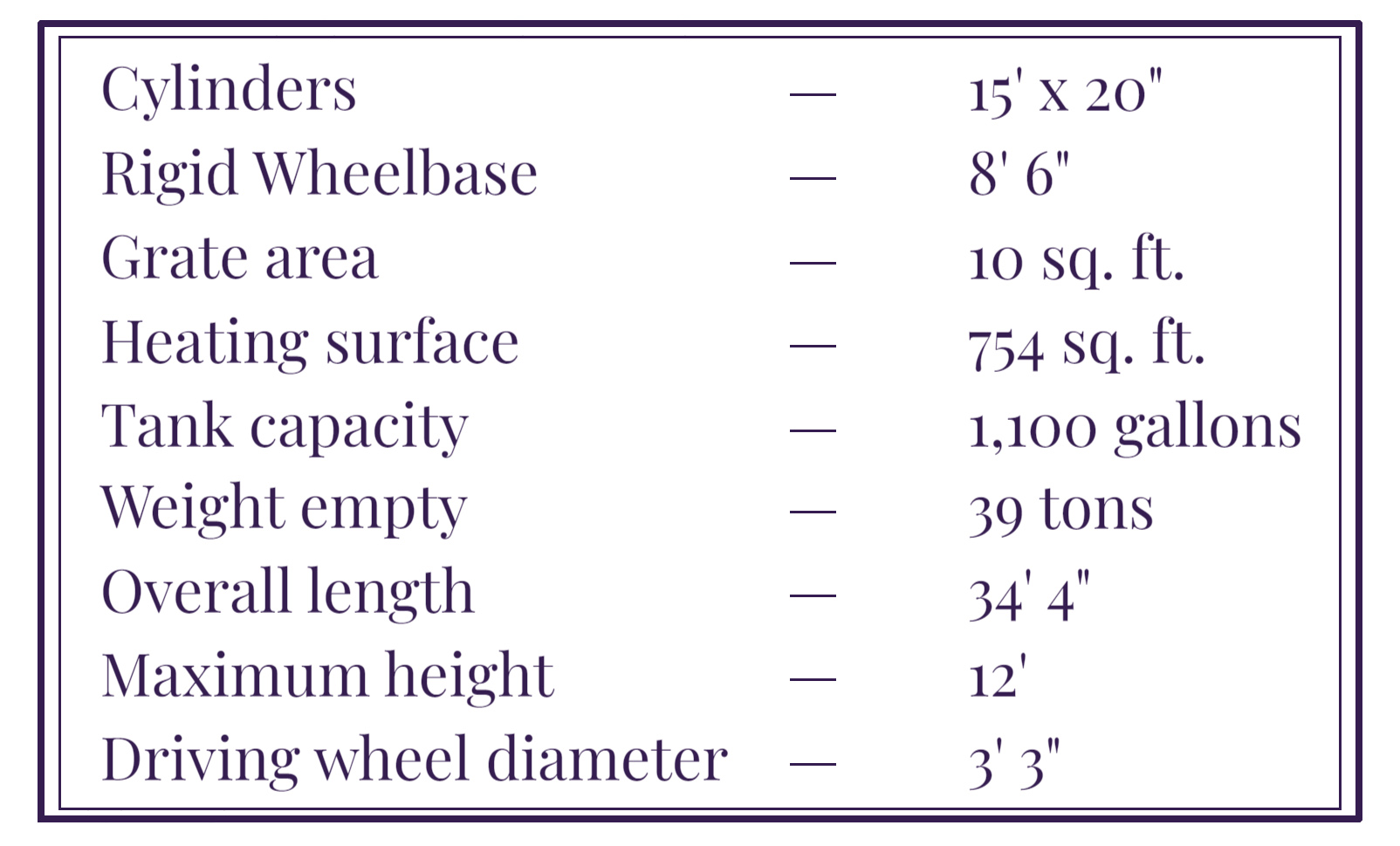

Statistics

Locomotives No. 5 & 6

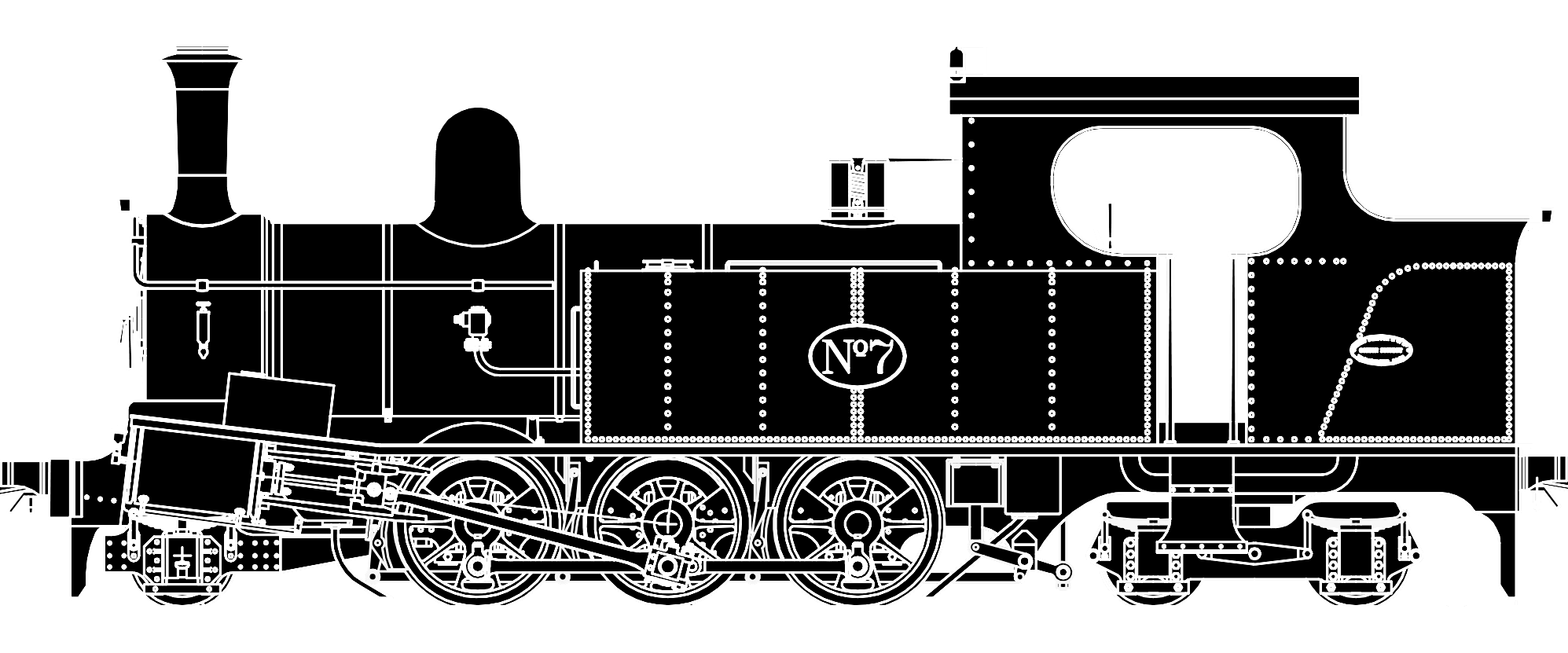

No.7-10: The Beyer Peacock quartet

After a bad experience with the Manning Wardle engines No.5 and 6 there remained a pressing need for more powerful but efficient engines to expand capacity. The Government turned to different manufacturers, Beyer Peacock & Co, in Manchester, UK. They were a well established company with an international reputation and the ability too outshop handsome locomotives.

The first engine, No.7, was ordered through the Crown Agents for the Colonies, and, once delivered 1895, quickly proved itself. A second, sister engine, was ordered quickly after, being brought into service a year later. The engines were similar to a class of 2-4-0 locos used on the Isle of Man Railway since 1873. The design was later enlarged as a 2-6-4 engine supplied to the Minas & Rio Railway in 1892; These became the template for the Malta locomotives.

The engines were reported as easy riding, with a better distribution of weight across the wheels that would have reduced wear on track and loco alike. So well received were this new pair that further orders were made, another in 1899 and a final one in 1905, bringing the final complement to four. These engines became the line’s most successful, being powerful, economic to run, able to haul up to twelve carriages on the 1:40 gradients, and were easily maintained at the Hamrun workshops. A photo of the interior of the workshops in 1912 shows one of this class entirely stripped down, its components scattered around the shop in various stages of refurbishment.

These engines found regular and continuous use from the day they were introduced to the final years of the railway. They were capable of hauling heavy loads of up to fourteen carriages at a time to Mdina. Innumerable photos exist of the four sisters in locations along the length of the line, illustrating how ubiquitous they became and how indispensable they were to the railway. They were seen often around the Hamrun yard, outside the old carriage shed where they were stabled, being coaled, or standing gently steaming in the sidings in reserve capacity or waiting instruction for shunting duties.

These engines arrived with decorative lining applied to their tanks and bunker, but this was lost as engines were overhauled and the livery simplified. There is some debate over whether the tall steam domes were polished brass or painted the same green as the standard engine livery. Because of the matching appearance in most photos, the latter is probable.

Of this quartet only No.9 was beyond economic repair by the time the railway closed, having last seen service in 1929. The other three of her class worked until the very last day, despite a reduced hauling capacity of between seven and nine carriages. For some time after services ended some of these engines were maintained in working order. Presumably they proved useful in the decommissioning of the line and perhaps to recover the remaining track. A rather dull and shabby No.10 was still able to raise steam in 1932, albeit in leaky condition, when it was appointed the ignominious task of shunting the other engines and rollingstock around Hamrun to be photographed ahead of their intended sale. In the event this was a futile effort, there being little commercial interest in them. Reputedly, the engines survived until 1937 before their eventual scrapping.

Statistics

Locomotives No. 7-10