Birkirkara

2 miles, 70 chains – Journey time 11 mins

Green heart of the line

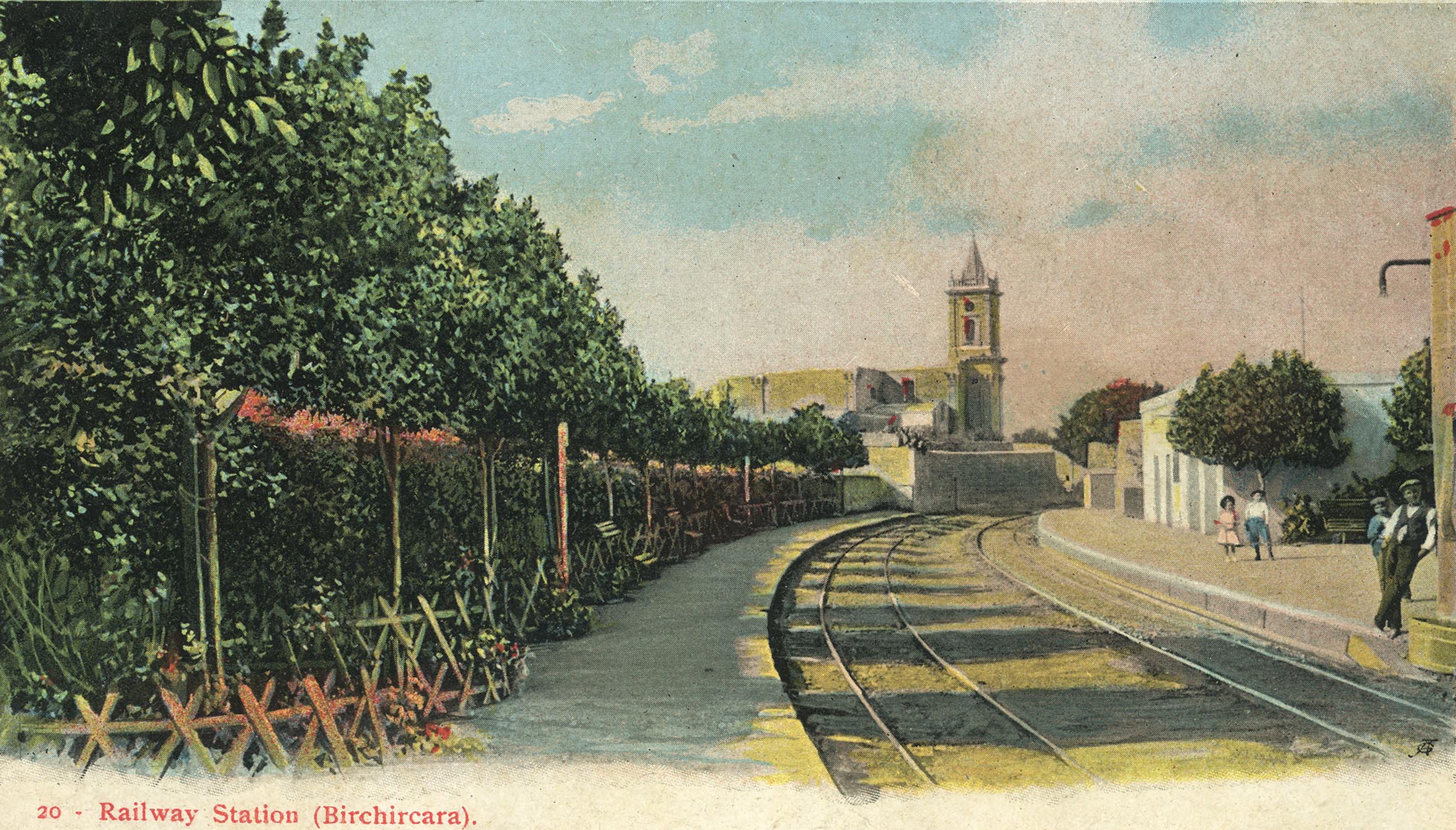

Birkirkara station was sited just to the south of the town, close to the old parish church, its tower having a commanding presence over the platforms. Here, the line intersected Strada Fleur de Lys at a sharp angle, with two bends that limited visibility, and a wide crossing. As well as being a danger, the acute angle was unkind to wooden cartwheels

Birkirkara marked the end of the busiest part of the Malta Railway. Classified as one of the principal stations on opening in 1883, it was provided with one of the Company’s larger standard format buildings. Like Hamrun, it was equipped with two platforms and a loop for services to pass each other. These platforms were mean in length and depth, less than 100ft by 5ft, and, despite the status of the station, the building was low, small, and with few facilities. The company’s limited financial resources would have limited any aspiration to provide something more hospitable. Passengers accessed it by a short approach road behind the building, where a cab stand was also provided.

Located on the northern platform the main building’s only real architectural embellishment was a pair of arches accessing the ticket office directly off the platform. This doubled as the only shelter, a tiny 10ft by 15ft booking room with a bench along one wall. The other half was split into two rooms one each for the booking clerk and station master. There were no other waiting facilities. Nearby, a simple water tower was erected at one end of the platform to top-up the engine tanks.

When the Government took over in 1891 General Manager, Lorenzo Gatt’s thoughts turned to improvements of one of the railways most frequented stations and address its severe shortcomings. After repeated complaints about the poor facilities and the lack of shelter, trees were planted in a strip along the back of the original platforms with flower beds, perhaps the genesis of the later campaign of greening the line’s stations. The platforms were extended as far as was possible, but the constrained site frustrated hopes of accommodating longer trains.

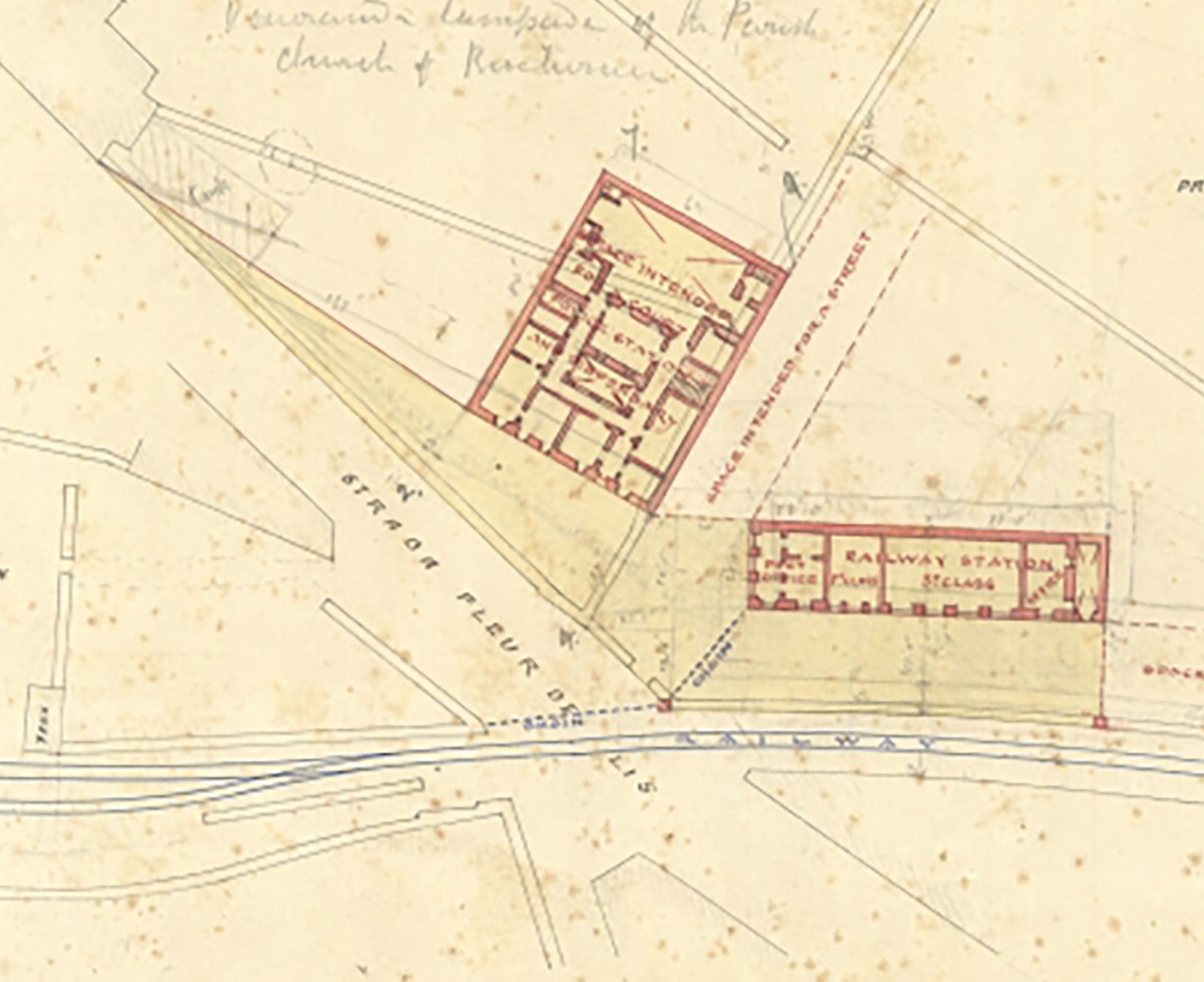

By 1894 there were ambitious plans in hand for the railway. For Birkirkara, these involved a proposed move of the whole station to the opposite side of Strada Fleur de Lys where it would have more space, and provide a grand new building that incorporated a post office. A court, police station, and dispensary in an adjacent building would have created a new civic centre for the town. Plans were well progressed for this and the construction of a new road tunnel under the railway, and presented to Government for approval. Despite a reported £1500 already having been spent, the projected cost was considered too great, and the proposal rejected. The expenditure on the extension of the railway to Mtarfa was, no doubt, a factor in the decision. Birkirkara would have to wait for better.

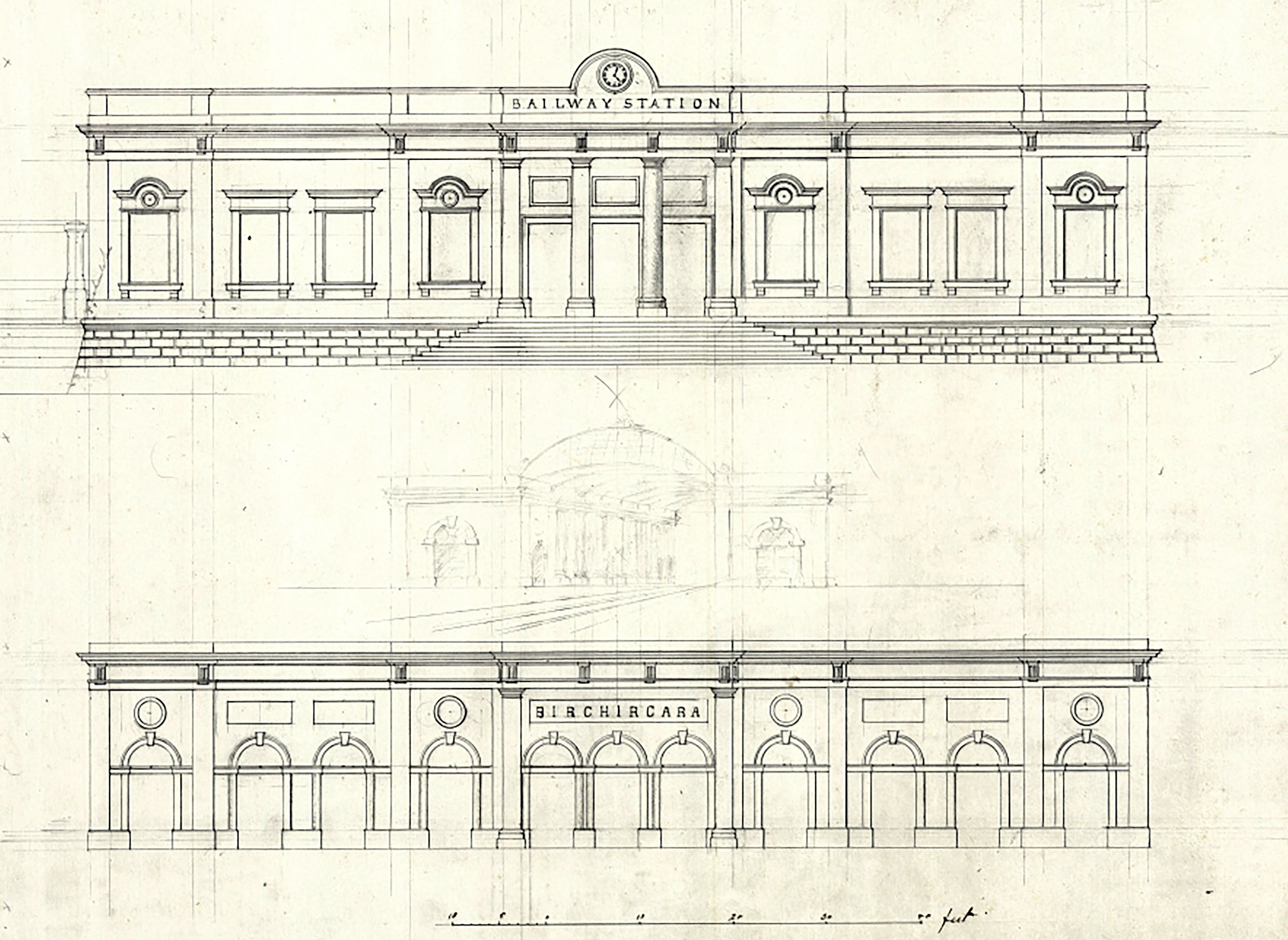

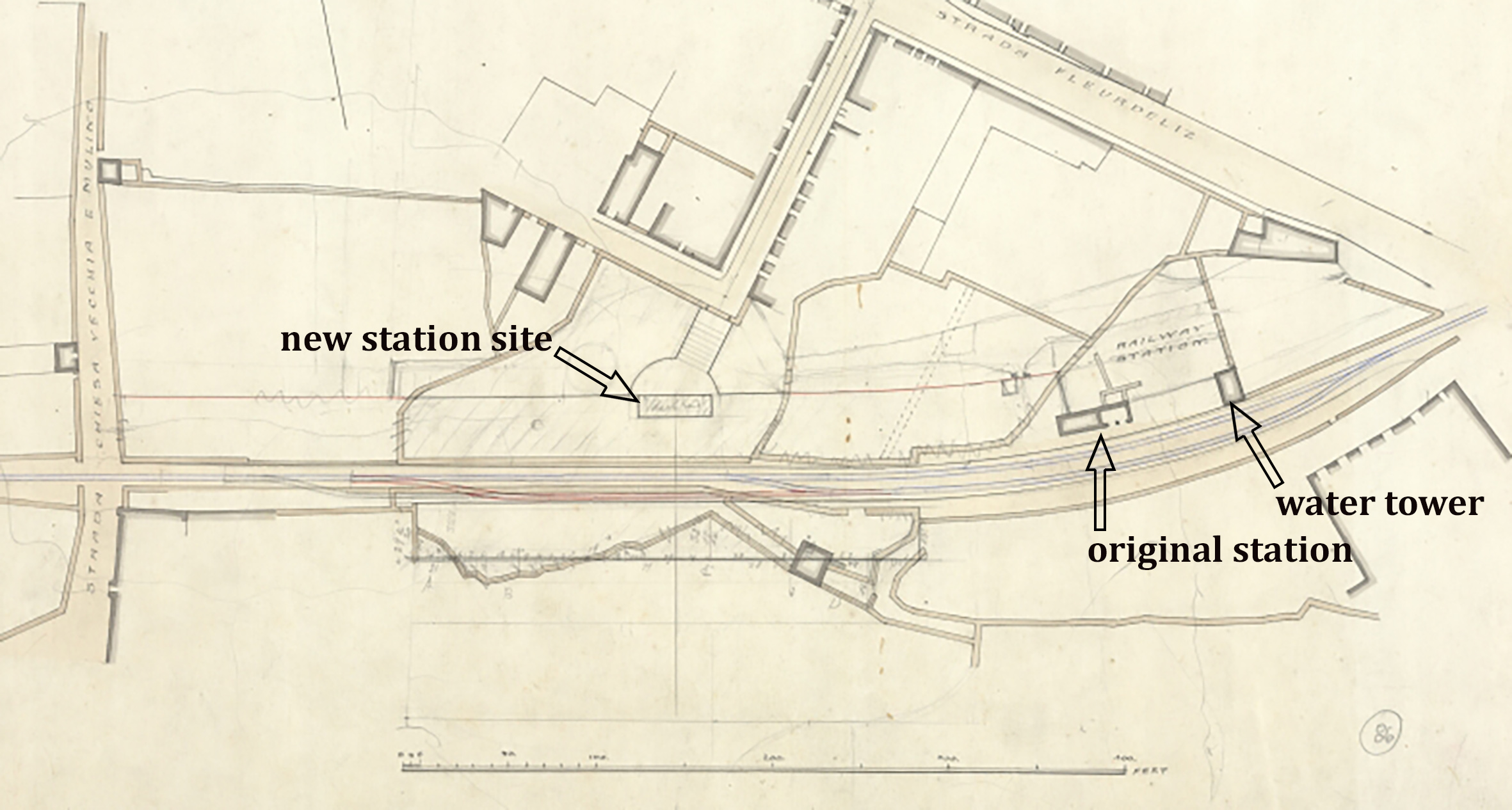

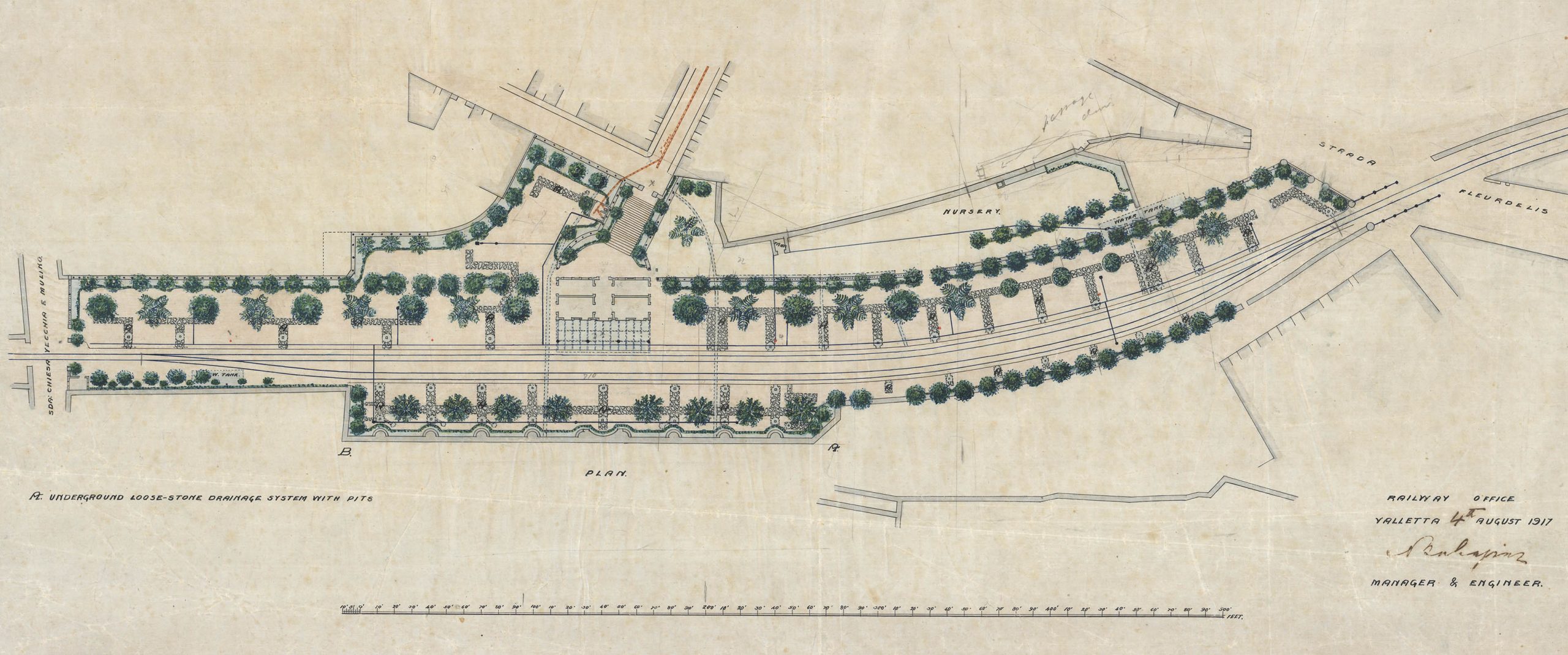

In 1896, Gatt’s chief engineer, Nicola Buhagiar, took over as general manager and continued to kindle aspirations of revitalising Birkirkara. There exist a number of drawings in the National Archives of Malta that track the development of his ideas. With his architectural training, they are likely to have been drawn by him, but may have been designs from the Office of Public Works, the department responsible for Government’s architectural and engineering output. Amongst the architects in that department was Andrea Vassallo who is known to have worked on some railway projects. Whoever was responsible, some of the proposals were crazily over-ambitious but all abandoned the idea of rebuilding across the Fleur de Lys Road. Some sought to improve the angle at which the railway and road met; a 1897 design doubled the length of platforms westward, proposed a large new building and gardens; a scheme developed through 1903-4 would have seen a mammoth scaled and ornamentally extravagant building on each platform, linked by an arched glass and steel roof across the tracks. It wasn’t until 1909 that capital was allocated for land assembly and works to develop a serious proposition.

By 1908 the station was handling 34 departures a day. This comprised through-trains between Valletta and Museum station and six were shorter shuttle service between the capital and Birkirkara. The station was woefully inadequate to cope with this traffic and, in the face of new and direct competition from the tramway on the route, the problem could no longer be ignored.

Much land west of the old station was purchased and long platforms laid out, more than doubling the existing capacity. After commodious new single-storey station building was finished west of the original, approached axially along modern Kulleggiata, the old building and water tank were demolished and their sites subsumed into more platform extensions. Surplus land was sold for development.

Essential to Buhagiar’s designs were the gardens. The earlier planting was retained but where new boundaries and retaining walls were required, hanging gardens were created, imaginatively designed to incorporate tiered planting, ornamental buttresses, stone troughs and planters along their tops, more planters being supported on corbels along the walls. An intentionally rustic character was maintained through the use of roughly coursed stonework, much of which was salvaged from demolition work in Valletta.

The rest of the platform area, that not required for operational use, was filled with tree pits and formal planting beds. When complete in 1910, the ultimate effect was stunning; a garden filled with flowers; more a park in which the railway was merely encountered, than primarily a station. The success of Birkirkara was repeated at Attard, then also in construction. In 1911 decorative cast stone urns were added as further embellishment, each marked with the initials MR and the date, many of which survive today. Gardens became such a feature of the railway that there were dedicated classes in Maltese horticultural shows for “cut flowers from railway stations”, the prize presented by the Island’s Governor on at least one occasion.

The new building had four rooms divided by a wide booking hall connecting the main entrance to the platforms. They were first and third class waiting rooms, ticket clerk’s, and managers office. Once tickets had been bought passengers passed onto the platform beneath a lofty and generously proportioned canopy. In a bit of typical ingenuity for the railway, the structure incorporated reused old steel rails, the cast iron columns probably being cast at the railway’s Hamrun workshops.

In the face of mounting competition and with declining income, such investment in Birkirkara’s station would not be repeated. The gardens became a green oasis for locals, no doubt promoting the use of the line as a more attractive proposition than the electric trams that travelled along dusty roads. By 1931, the last year of railway operation, there were only eighteen departures a day.

In 1935, four years after the line closed, an additional storey was added to the station building as it found a new use as local council offices. This and the public value of the gardens ensured the station’s preservation. As part of a revitalisation in 1987 the last surviving Malta Railway carriage was restored and set up outside the station, though thirty years of exposure had severely decayed and risked complete disintegration. Through the efforts of the Malta Railway Foundation the carriage was salvaged, restored, and returned again. They too were responsible for the glass shelter that now protects this precious survival from the elements. Their most recent achievement has been the opening of the Malta Railway and Tramway museum in the old station.

Previous Station / Next Station