Private initiatives: 1870-1890

A fitful gestation

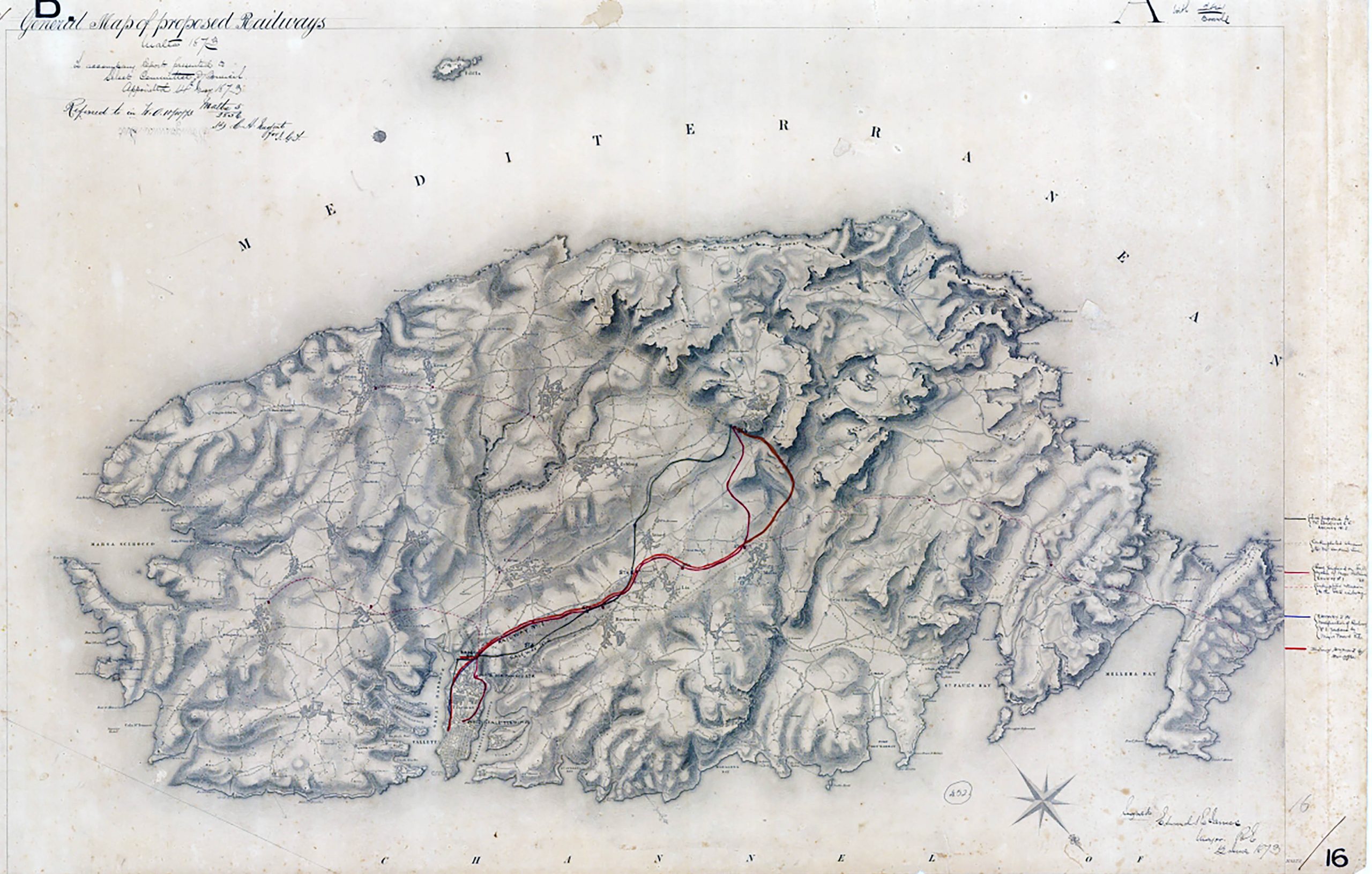

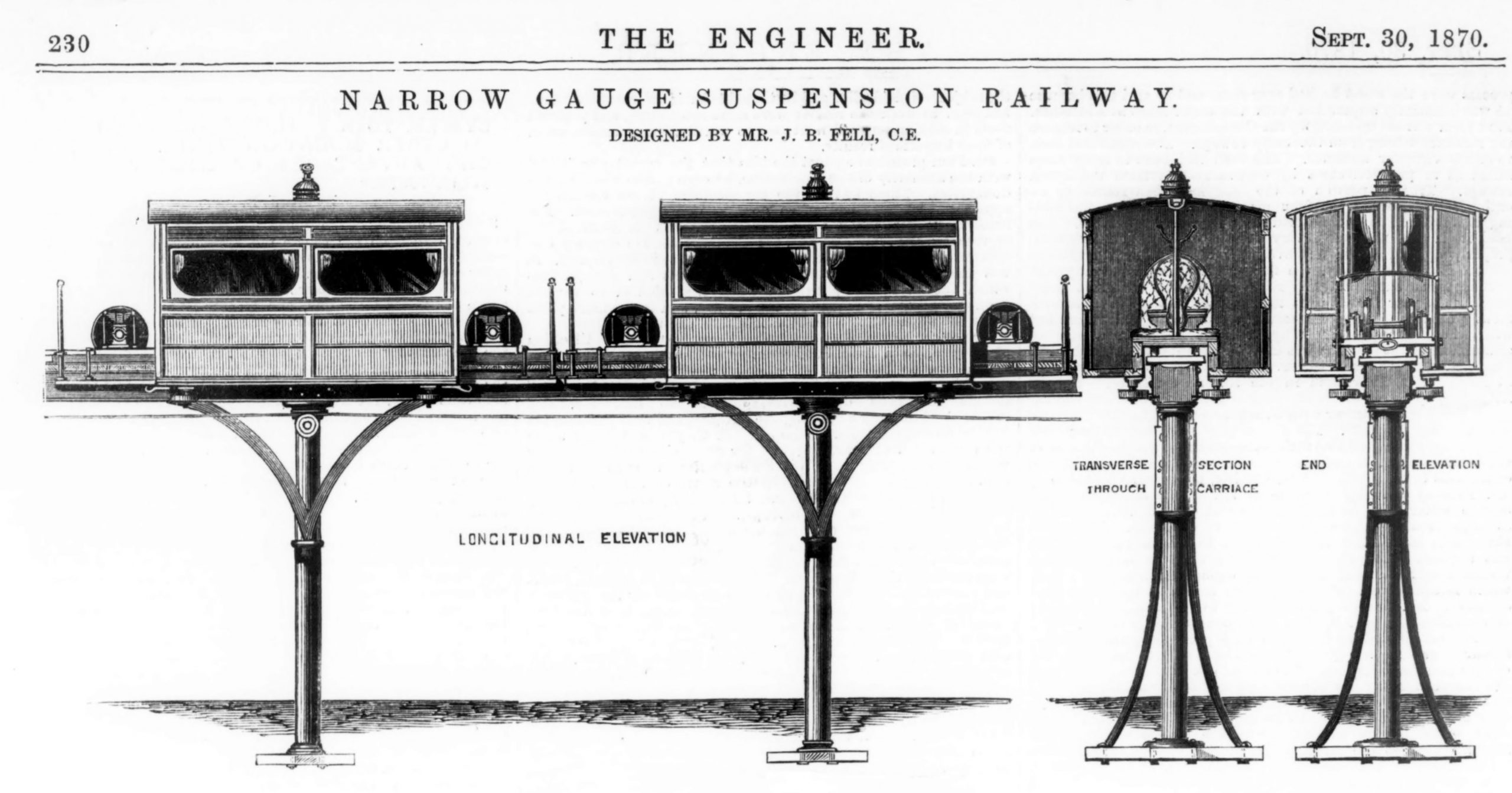

The first proposal for a railway connecting the old and new capitals of Malta was laid before Government in 1870 by, John Scott Tucker, resident engineer of the Anglo-Maltese Hydraulic Dock Co. who was then engaged in a new floating dock in the harbour. The idea appeared to fizzle-out, and it would take another three years for new interest to present itself. As it happened, Malta suddenly found itself with several different plans clamouring for its support. All sought a concession from Government for a line to Mdina but varied in the intended course and approach. One, that by a Major Hutchinson, probably of the Royal Artillery, was an unconventional proposal for a trestle-type railway on an experimental model developed for the Aldershot narrow-gauge suspension railway, invented and patented by John Barraclough Fell. Hutchinson’s submission was accompanied only by an “artist’s impression” of the proposed system. The most developed plan, for a metre-gauge railway, was presented by Civil engineer Charles Andrews who was then attached to the Naval Department in Malta and engaged in docks and waterworks. He’d made a comprehensive survey of the island and was able to present a realistic scheme, well-supported by drawings and justifications.

Major James of the Royal Engineers, one of the Government’s appointees to the Select Committee tasked with reviewing the rival proposals, developed a third proposal comprising elements of both proposed routes. Perhaps allying himself with a fellow military man, James favoured Hutchinson’s proposal for the peculiar Fell system purportedly for its low cost. However, its eccentric design failed to win favour, and the committee recommended to Government that Andrew’s scheme be granted the concession which was quickly drawn up. The conditions were onerous, committing the promoters to completion within 13 months from Jan 1st 1874. An additional four extensions were opened at specified dates over the following six years, fares were to be set by the Government, and provision included for stiff financial penalties and the threat of forfeiture if delays and deadlines were missed. They gave Andrews and his business partner E Rosenbusch (an entrepreneur who introduced of international telegraphy into Malta) one year to form a company and raise all the required capital to begin the works. One of the conditions set out in the concession would result in the eventual collapse of the railway as a commercial concern. Requirements to maintain an uninterrupted service stipulated stiff fines should it be levied if services were curtailed for as much as one day, and complete forfeiture of the railway should trains be stopped for more than three months. More of this later…

No doubt to his frustration, J.S Tucker reappeared out of the woodwork to find a competitor had been awarded the concession he surely considered his. He’d returned with shareholders already subscribed to stock options for his proposal, and approval of his alternative plans from the War Office. Armed with a list of his own demands he argued his case for the concession, but, with it already granted to Andrews and Rosenbusch, it was a futile exercise and he was rebuffed. When the deadline to raise capital expired without the partnership having been able to find funding, Tucker pushed again to take it on, but his demands remained unacceptable to a new select committee and it was re-awarded in Andrews’s favour, buying them more time to fundraise. At the same time, an alternative promoted by Giuseppi Mirabita, a local concern, was also considered by the committee. Mirabita and his sons had found difficulty in securing funds, and whether they were taken seriously for taking the responsibility on isn’t clear.

Andrews and Rosenbusch eventually managed to form the Valletta-Notabile Railway Co Ltd in 1876, with £100,000 capital, but lacked the strength of their initial conviction and the company dissolved, ceding their concession back to Government the following year. Behind the scenes the Mirabitas had been working hard to develop their railway ambitions, commissioning their own engineer to provide drawings. Their first company acquired the concession after Andrews abandoned it, but later collapsed. A new partnership was formed with the British railway and civil engineers Richard Gervase Elwes and his partner George Wells Owen who were to provide their professional services in return for shares. This company collapsed too when the Maltese Courts cancelled their contract with the Government and the Mirabita’s declared “non-suited”.

Getting a plan together

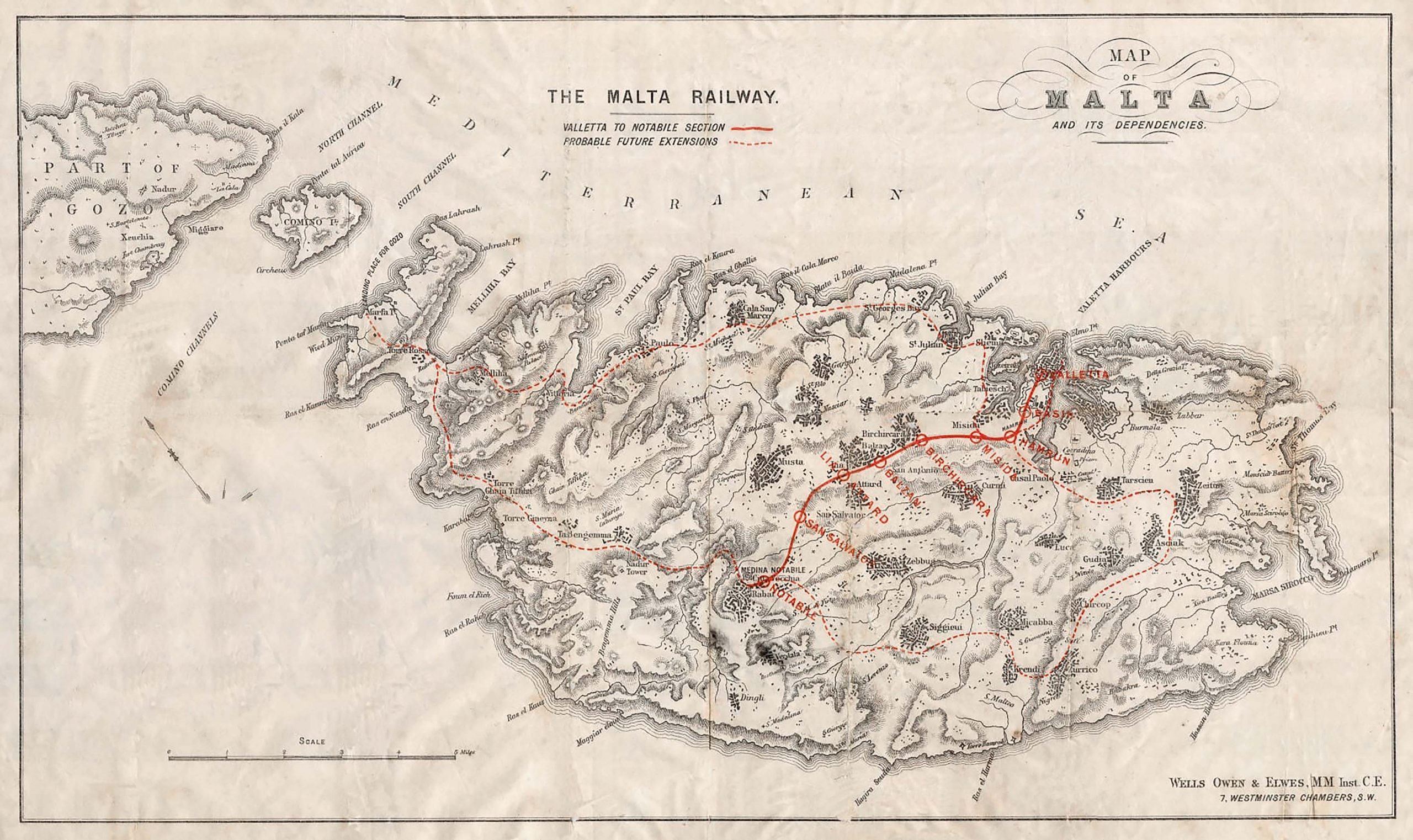

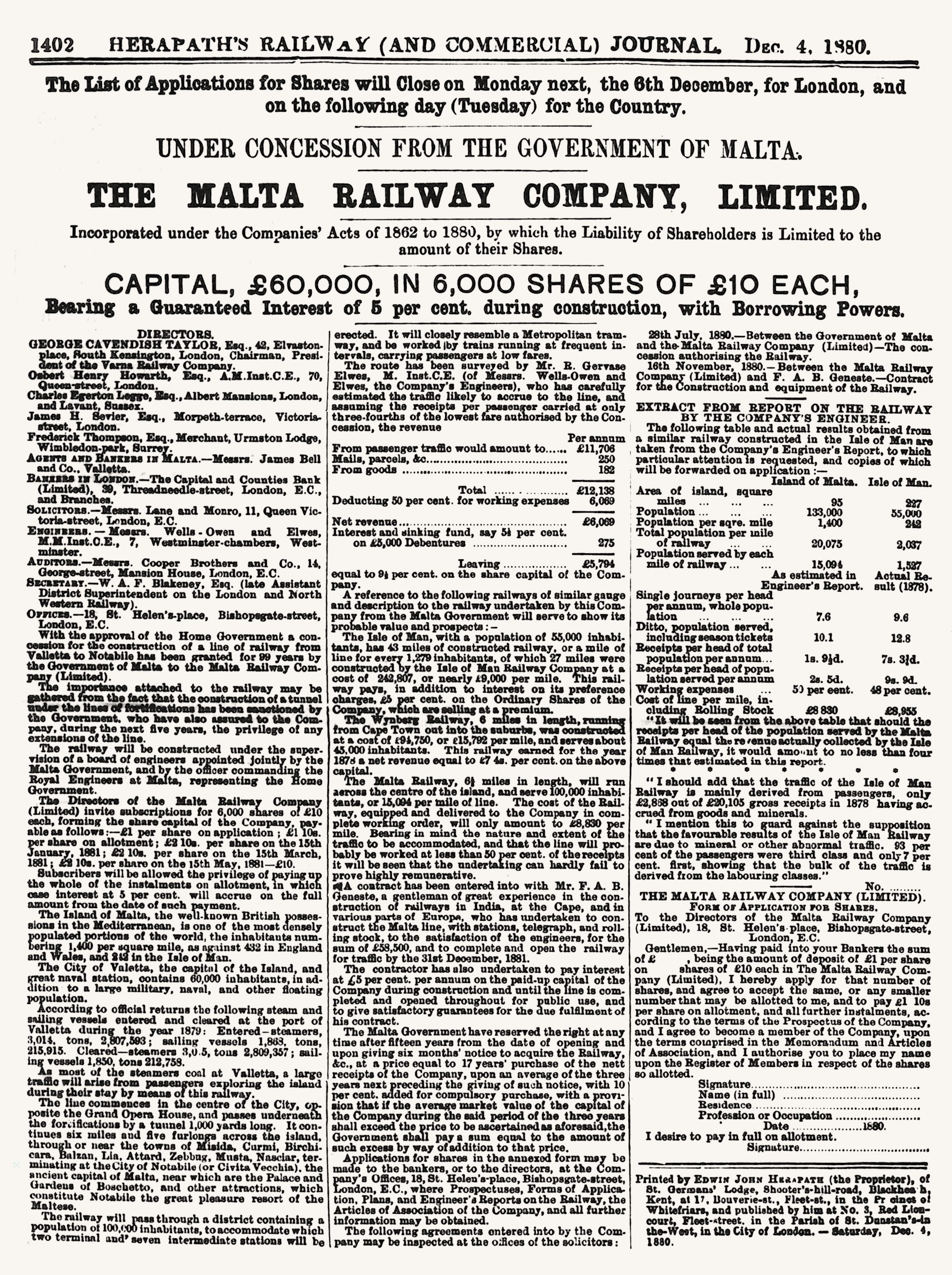

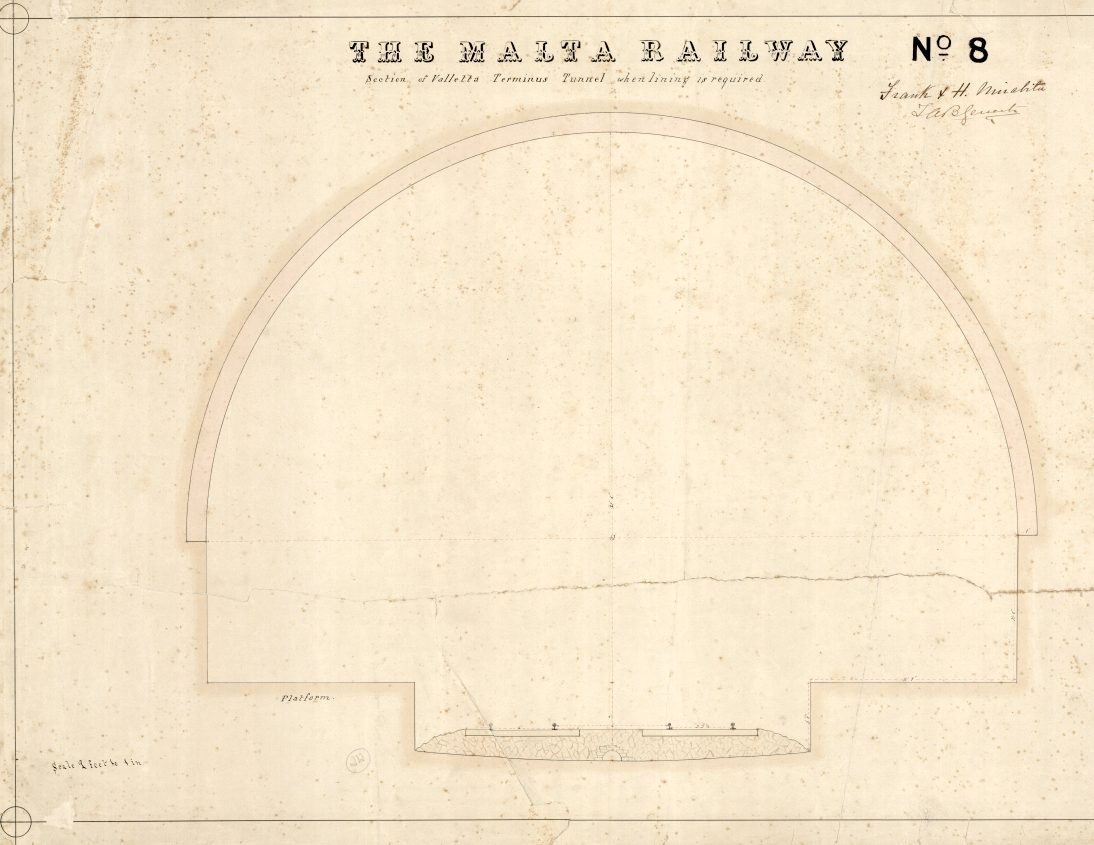

Undeterred by the collapse of the Mirabita’s company Richard Elwes maintained faith in the idea and continued work on plans with the hope of securing Government support; this he did in July 1880 when a new concern, the Malta Railway Company Limited, was granted similar terms as previous undertakings. The company was registered in London with a small board of five directors led by Captain George Cavendish Taylor, a Crimean War veteran who, on leaving the army, had become wealthy from his investments and directorship of several railway companies in the UK and abroad. Lieutenant James H Sevier was another former military man and Osbert Henry Howarth a minor civil engineer. Charles Egerton Legg was perhaps the most well-connected director, the grandson of the second Lord Dartmouth, and heir to a small fortune and a modest country estate. Frederick Thompson, described as merchant and gentleman, stepped down in 1883 when the number of directors was reduced. By February 1881 these men had been joined by the irrepressible William Roebuck, another engineer, who worked tirelessly in the railway’s interests. All the directors had London addresses with no local Maltese representation on the board. They came from diverse backgrounds, with varied levels of experience, but had come together around the Malta railway enterprise.

Prospectuses, drawings, and reports were circulated to attract investors to secure the £60,000 required. This would cover capital costs in building the line and stations, acquiring rollingstock and locomotives, and getting the railway operational, with about £2000 as contingency or initial running costs. Although the initial share subscriptions only raised £49,830, it was enough to get the project rolling, hopes that remaining shares would be taken up as development progressed. Engineers Elwes and Wells Owen were both shareholders, together holding the largest proportion of company stock, perhaps taking an allocation in lieu of payment for the work required of them in designing the works.

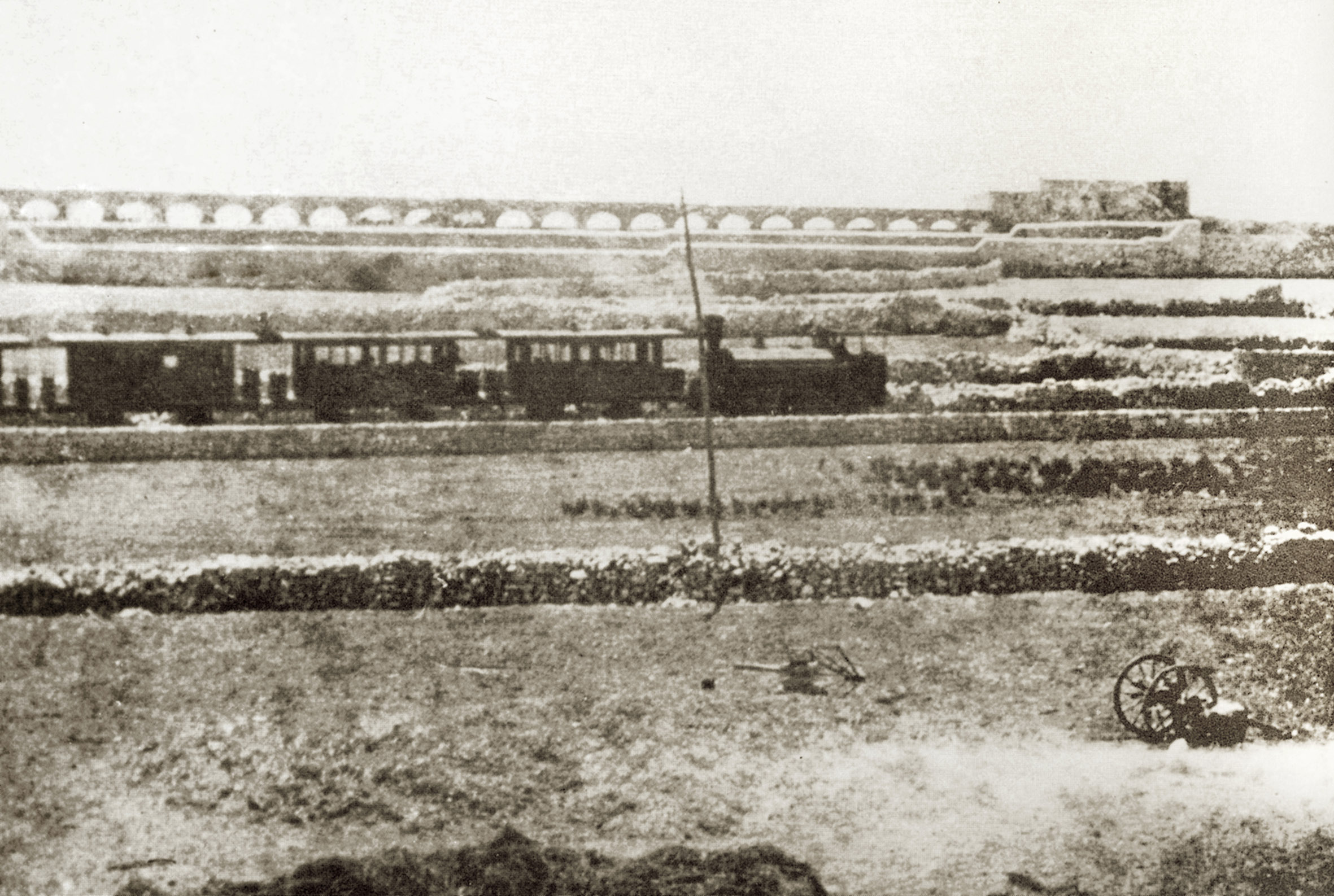

Liberal use was made of work commissioned by the Mirabitas, who in turn had built their plans on Andrew’s failed scheme. Estimates of traffic were optimistic, an annual income of £12,000 projected with operating costs no greater than half that sum, suggesting a profit of at least £6000 annually. The timetable would comprise of a half-hourly service of thirteen trains in each direction. Capacity was likely to be 1,300 passengers daily with an average of 50 travellers per train. Like previous endeavours, the line would link Valletta and Mdina with a route taking in the quick-developing industrial suburbs of Hamrun and Birkirkara, and the more affluent environs of San Anton and Attard. Several additional rural stations would encourage feeder traffic from nearby villages. As the closest convenient station out of Valletta, a railway depot would be constructed at Hamrun.

The Government would need to agree the proposals delegating this responsibility to a Supervision Board. Two appointments would be made to protect the interests of the Government and public, and a third would represent the British military interest; The commanding officer of the Royal Engineers was to take on that role though further consents would be required from the War Office should they be concerned about the security of the island’s fortifications. With these parties having power to veto proposals, the authorisation processes would come to dog construction as interference and conflicting views prolonged negotiations and delay progress.

With Government support, funding largely in place, and initial drawings being produced by Elwes and Wells Owen, things were inching towards breaking ground in Malta. In November 1880 the contract for building the railway was signed, not with a contractor, but with another engineer, Frank Alexander Brown Geneste. On paper at least, Geneste had good experience in undertaking major railway works. It’s unknown if tenders were invited from other parties or whether Geneste was appointed without competition. Who recommended him, or how he became involved in delivering the railway is equally unknown, but he signed a contract binding him to complete the railway for the sum of £58,000 and by 31st December the following year. With no company behind him it would be Geneste’s responsibility to find his own contractor to build the line. Presumably with the knowledge of the Malta Railway Company directors, he subcontracted this work to none other than the Frank and Annibale Mirabita, entering into contract with them in December 1880. It may have been that Elwes and Wells Owen continued a relationship with the Mirabitas and ensured they were presented to Geneste as the preferred contractor, but, with the relationship between former partners now distorted, the scene was set for later dramas.

Completion and Inauguration

Construction of the line started in March 1881 and would take twice as long as hoped. Delayed by bureaucracy, disputes, and poor management, the gradual progress of the line inland from Valletta was excruciatingly slow. A more detailed account of the construction can be found in The Works. Things looked brighter by November 1882 when company chairman George Cavendish Taylor declared to the collected investors at their AGM that:

“If we had not pulled together as we have done, by constant attention and constant labour, this concern would have gone to the dogs long ago. You would not only have been short of your interest, but you would not have had any principal to pay interest upon; because, as I have already told you, your concession would have been forfeited, and the whole thing would have gone to the Maltese Government.”

By the time completion was in sight the original projected cost had been significantly exceeded, eventually calculated as £76,971. Frank Geneste, having been forced to relinquish his contract due to insurmountable issues, had instead been installed as consultant engineer, before he was offered the role of General Manager. This would place on him the responsibility of preparing the railway for operation and the expectation that he would operate it efficiently and profitably. Despite Geneste repeatedly promising the directors that the railway would be complete by late-January 1883, it wouldn’t be until early march that public services would commence.

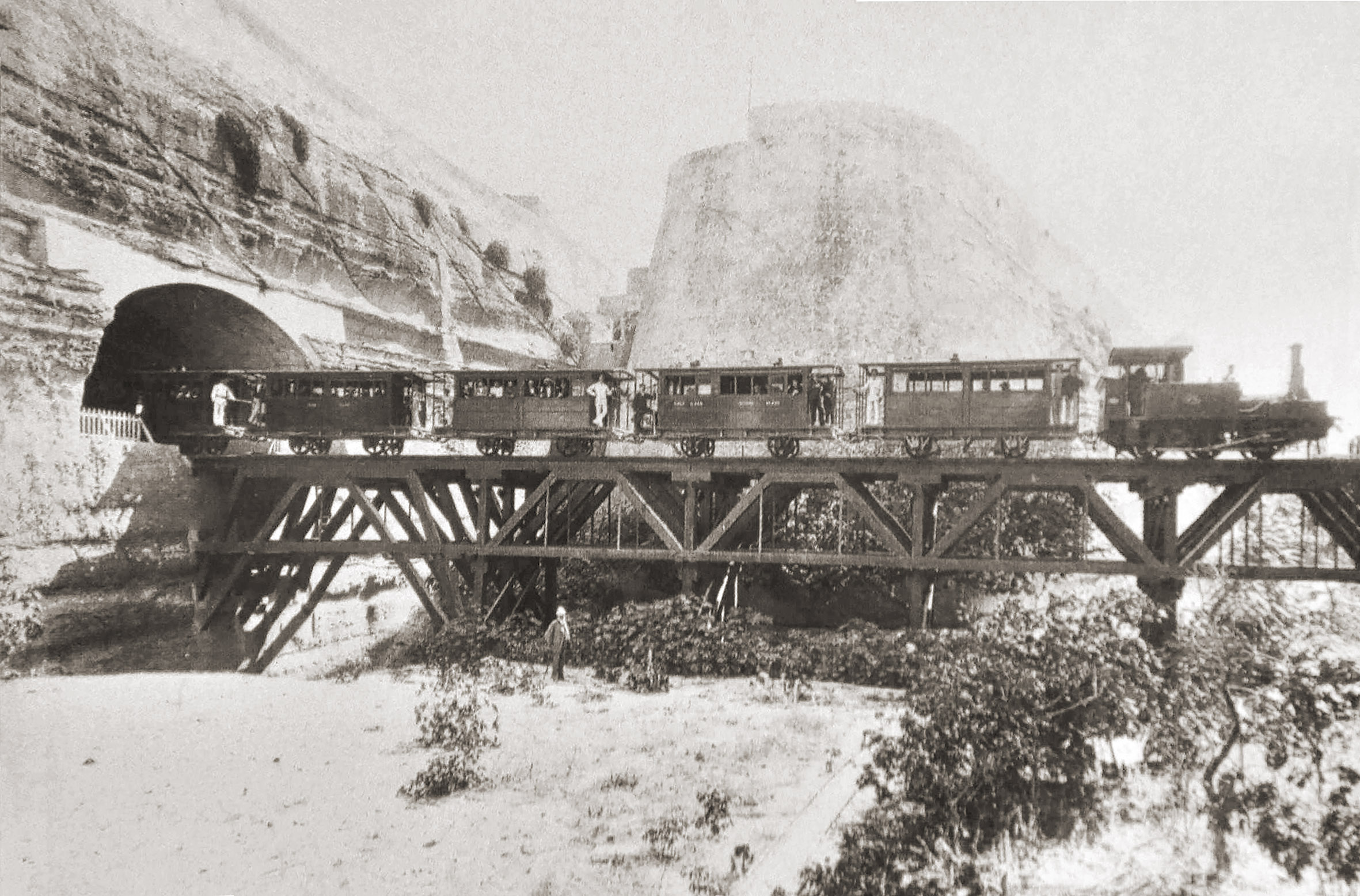

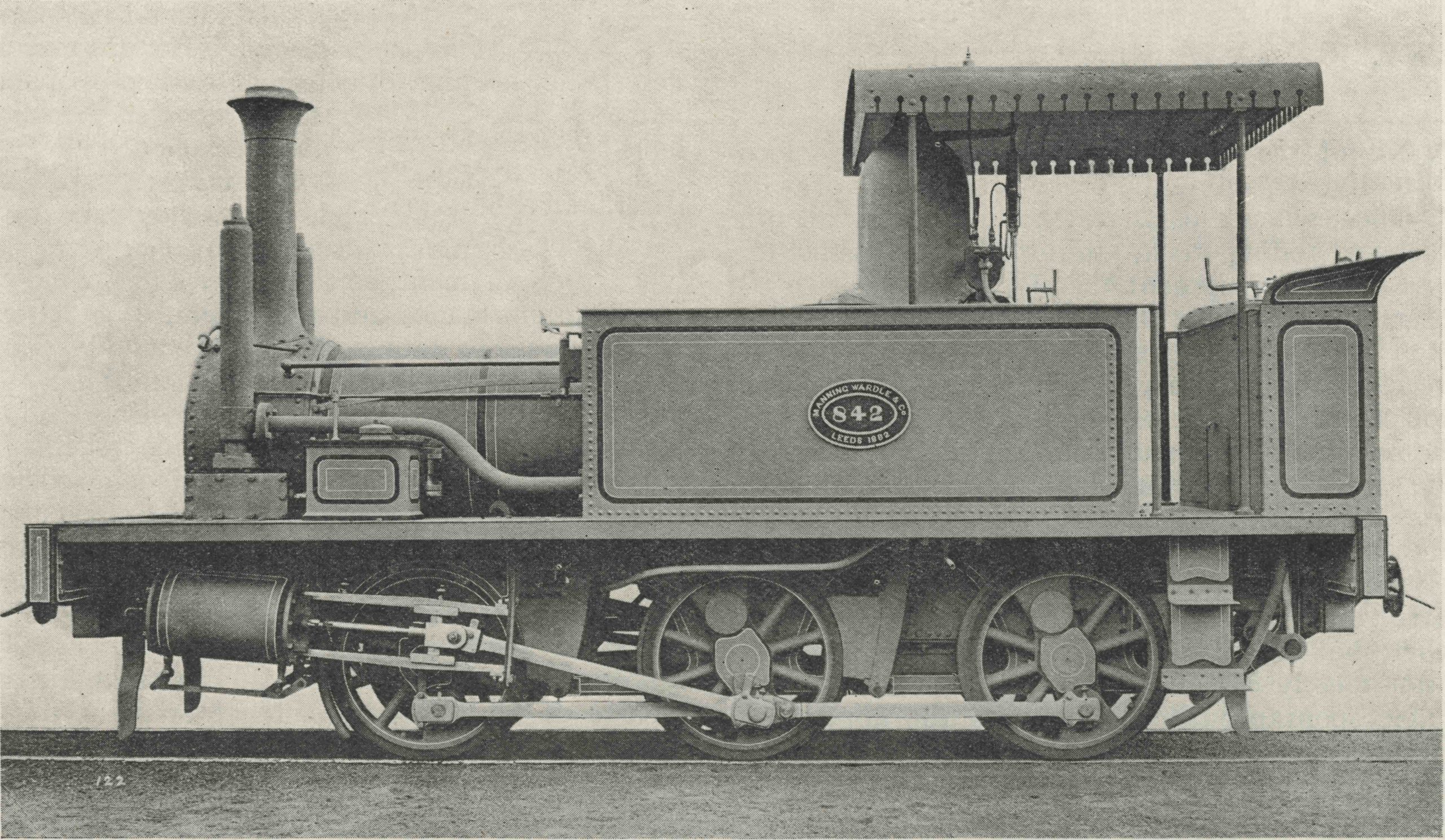

The first locomotive arrived in Malta from Manning Wardle engineers of Leeds at the end of 1882, a second arriving in January 1883. This allowed time for training the enginemen and the testing of both the engine and infrastructure ahead of opening. Officials from the Office of Public Works and other Government representatives were invited to attend trials and sign-off the works as fit and safe.

Rollingstock was shipped from Swansea Wagon Builders for final assembly on the island. There were twenty carriages in the initial order, ten 3rd class, six comprising of 1st and 2nd class compartments, three open workmen’s carriages, and a most opulent Governor’s carriage. Early photographs suggest 3rd class and workmen’s carriages were gloss-varnished teak with the higher class distinguished by the same olive green livery as the locomotives. Only two low ballast wagons were ordered. The original financial projections including for goods traffic, but the potential of this was never explored.

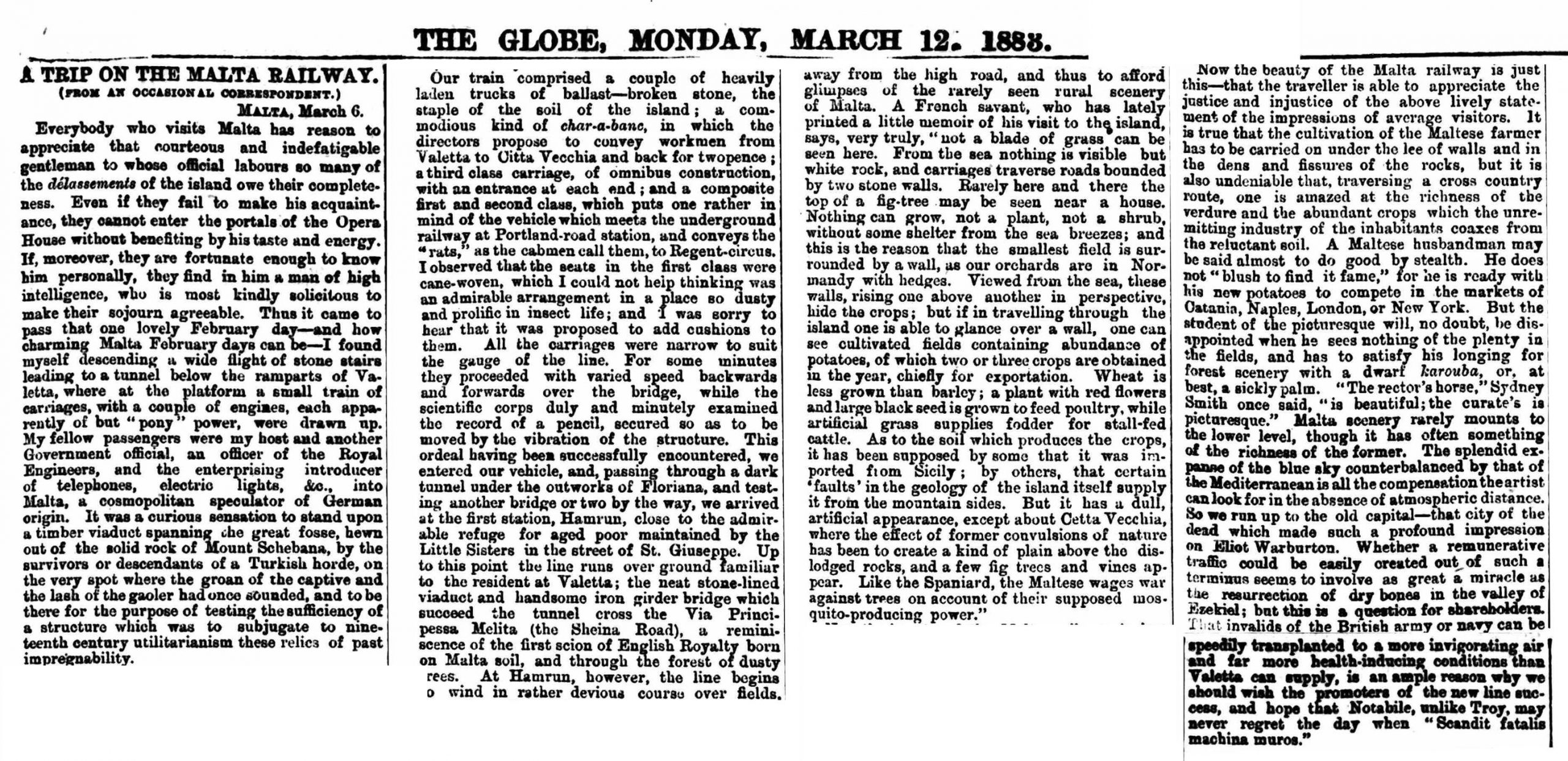

A delightful description of one of the pre-opening events survives from February 1883, though published after the actual inauguration. The writer eloquently describes a train of heavily loaded ballast waggons and a mixed train of carriages being hauled by both available locomotives. Accompanied by Webster Paulson, Clerk of Works in the Office of Public Works, they explain the train being passed backwards and forwards over the timber viaduct across the main ditch at Valletta, engineers checking for any deflection in the structure. It was probably during these tests that the opportunity was taken for official photographs. Despite enjoying the novelty, the correspondent for The Globe seemed doubtful of the line’s potential on their arrival at Notabile:

“Whether a remunerative traffic could be easily created out of such a terminus seems to involve as great a miracle as the resurrection of dry bones in the valley of Ezekiel; but this is a question for shareholders.”

Curiously, it appears that Edward Rosenbusch, “a cosmopolitan speculator of German extraction” and one of the promoters of the earlier failed railway scheme with Andrews, was also aboard this train. His company, the Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Co, was likely called upon to supply the telephone system to be relied upon to control the passage of trains along the line.

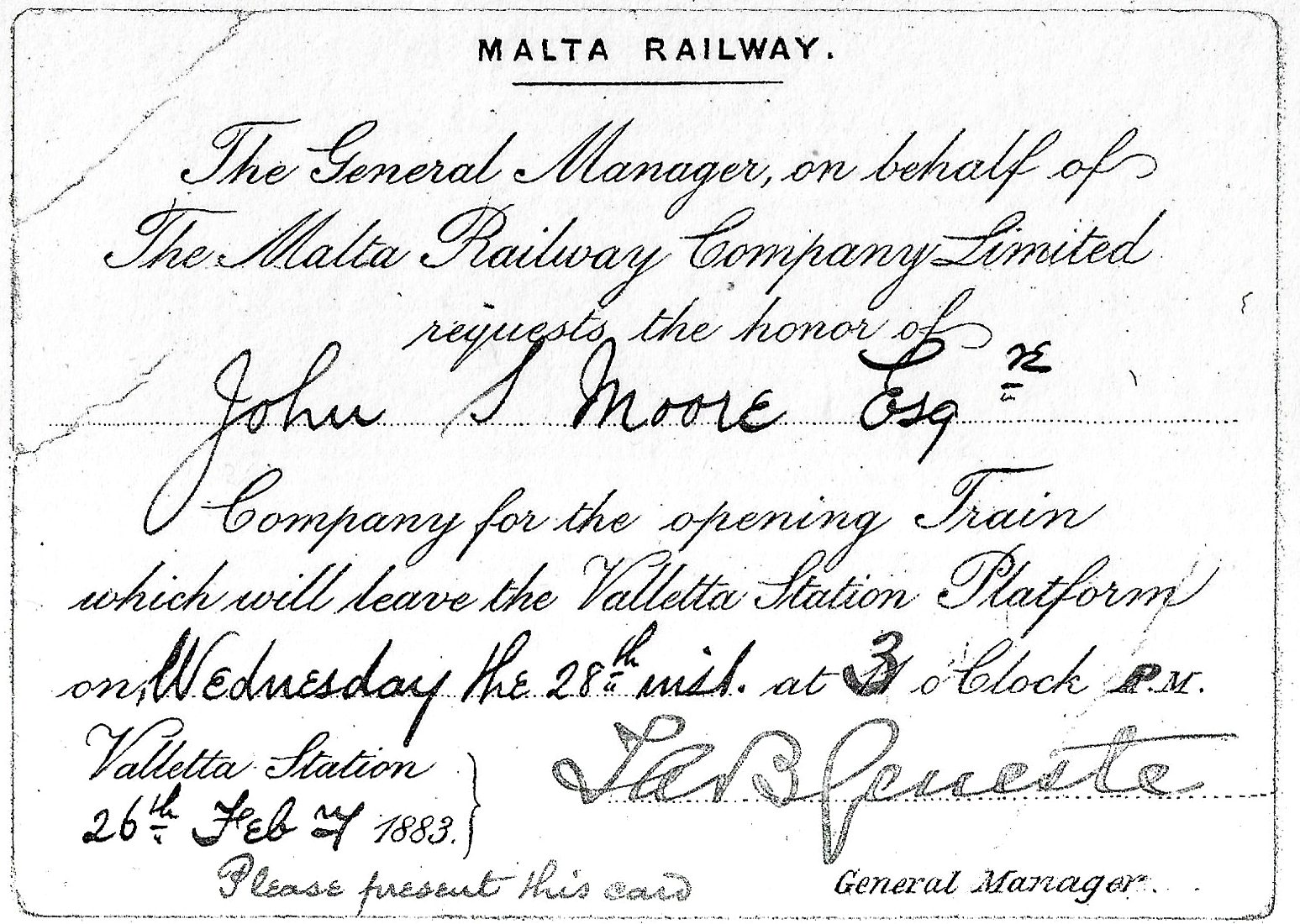

Eventually, work was sufficiently complete, and authorisations secured so that the inauguration date could be settled upon as Wednesday 28th February 1883. None of the Mirabita family were recorded as having attending the event, and the company directors were unable to attend, leaving Geneste, as General Manager, to be the focus of the day’s accolades. A valuable and detailed description of the events of inauguration day was published in the following morning’s Malta Standard which, it’s considered, is suitable to repeat at length:

OPENING OF THE MALTA RAILWAY

The opening of the Malta Railway, which took place yesterday, records an event in the annals of this Island, of which the inhabitants may well be proud. After long expectations the idea mooted years ago of constructing a Railway has been realized. This sea-girl isle can now boast of a line connecting the new capital with the old, which in time may extend itself all over the surface of the Island, constructed under the superintendence of F. A. B. Geneste Esq., in the face of difficulties which the general public can hardly realize. Wednesday will indeed be remembered as a red letter day. Regular Queen’s weather prevailed. A bright sun shone from a cloudless sky, the solar rays being, however, tempered by a fresh breeze from the North, and we cannot but help hoping that the future of the Railway may be as cloudless and bright as the firmament above us during the day. An account of the proceedings cannot but prove highly interesting to all, high and low, rich and poor. From an early hour the approaches to and around Valetta terminus were crowded with people anxious to get a sight of the “Benediction ” train which was to start at 11 a.m., the police having no easy task in keeping back the surging crowds, who threatened to demolish the railing at Porte Reale. Punctually at the hour fixed, His grace the Archbishop of Malta accompanied by his Canons and other clergy proceeded from the Victoria Church in Strada Mezzodi to the Station, where he was received by the General Manager Mr. Geneste and a number of the clergy; a handsome bouquet being also presented to His Grace. The station having been duly blessed, the train started for Notabile, His Grace and some fifty of the clergy occupying the three first carriages, the fourth and last carriage being occupied by a few ladies, the Rev. mother of the Sliema Convent, Mrs. Geneste, Mrs. Nauda, Mrs. Gaizia and Mrs. Laferia all feeling pretty safe as it is well known that it is a fundamental principle of Railway Management “Never kill a bishop.”

After a short stay at Citta Vecchia, the party returned arriving at Valetta a little after midday, one and all expressing their satisfaction and pleasure. The chief feature of the proceedings was the departure of the “opening” train, which took place at 3 p.m. A party of about 150 gentlemen and a few ladies had been invited to take part in the ceremony, amongst whom were H. E. the Governor, Lady Canynghame, the Heads of the Civil Departments, representatives of the Army, Navy, Church and Press and of the community in general.“

“A special carriage was placed at the disposal of His Grace the Archbishop, who would have again accompanied the Train had he not been somewhat fatigued after the arduous duties of the morning. Special carriages were placed apart for H. E. the Governor and Lord Alcester, the latter however was unavoidably prevented from being present.

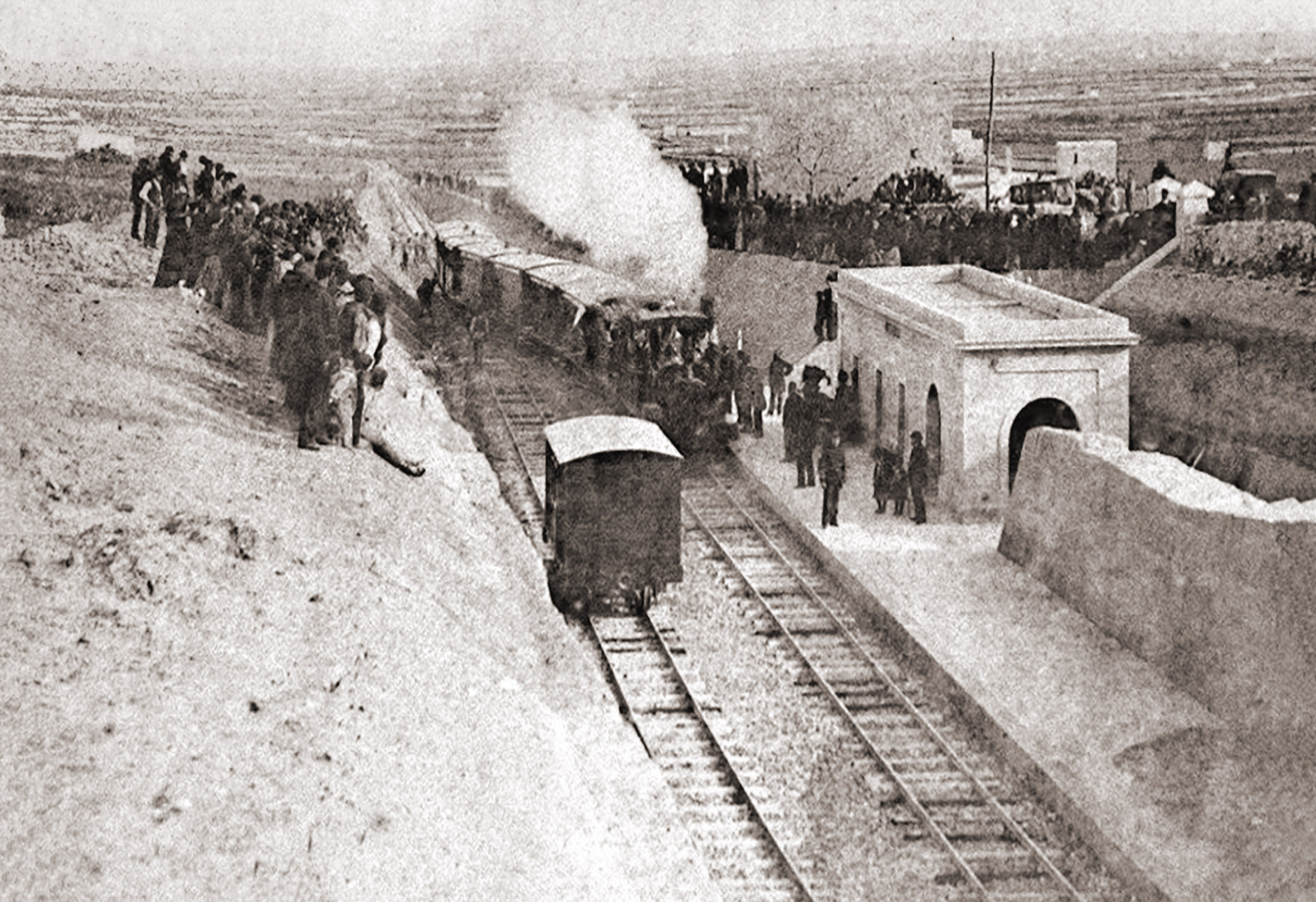

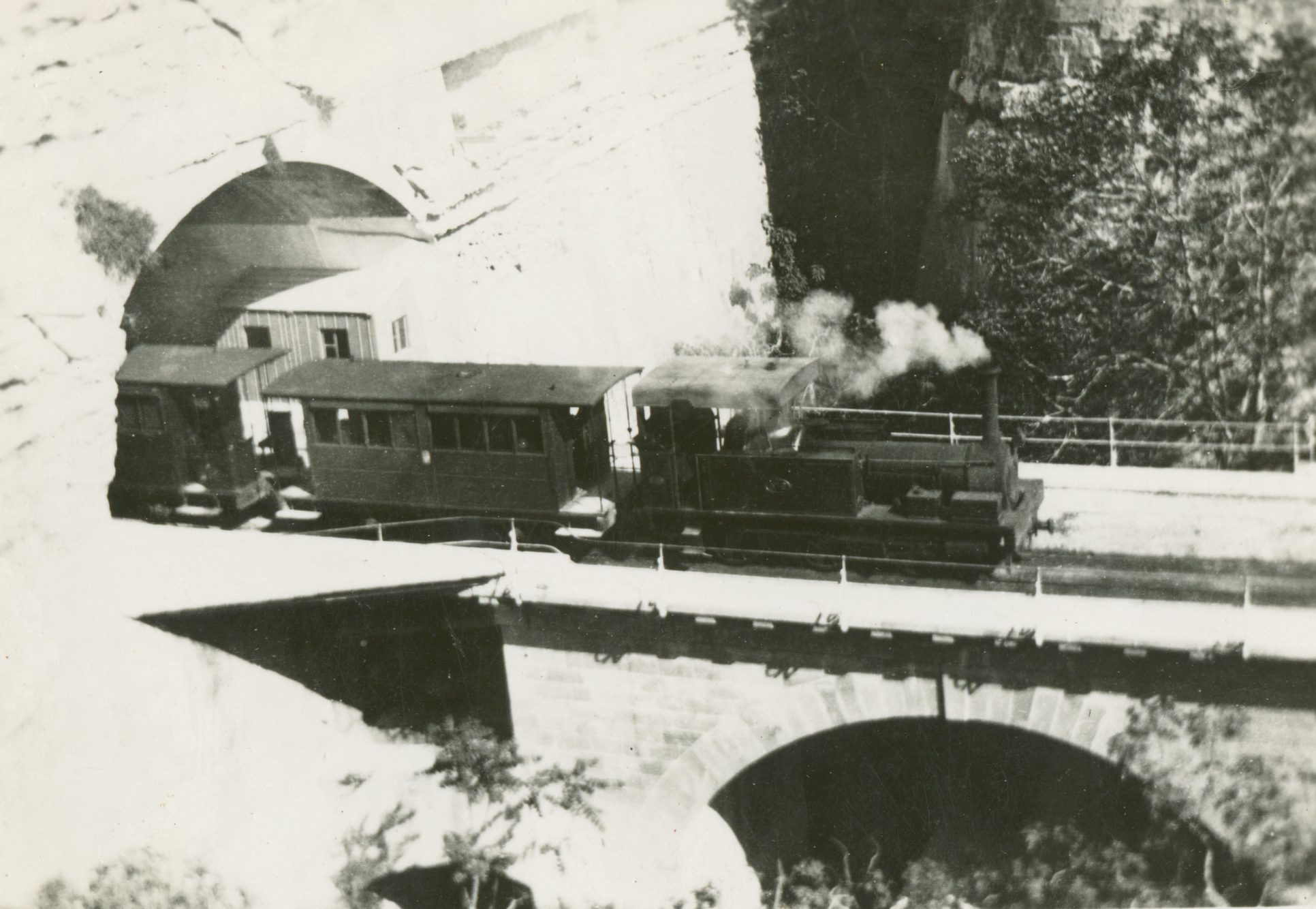

At 3 p.m. precisely the train left Valetta station, and on it sped through the tunnel, passing Floriana, Hamrun, Misida, Birchircara, Casal Lia, St. Antonio, Attard, St. Salvatore stations and reaching the terminus at Notabile in 25 minutes. Along the whole of the line at different points the people came out in their thousands to witness the “Iron Horse.” who was gaily decorated with flags and flowers. Wonder and pleasure seemed intermingled on the countenances of all. There was an inclination to cheer, but they did not know how to do it.

On arrival at the Notabile platform Mrs. Geneste was in waiting to present Lady Borton with a handsome bouquet, but her ladyship was unavoidably prevented from being present owing to indisposition and Captain Borton received the floral offering on the part of her ladyship. The party then proceeded to the tents on the road above the station, H. E. the Governor and Mrs. Geneste leading the way. Refreshments were then served in the tents. Glasses having been filled with champagne, H. E. the Governor made the following speech:-

Ladies and Gentlemen,

I will ask you to allow me to say a few words on this occasion on which we have met to inaugurate an undertaking which is so likely to benefit this Island that it appears to me to merit a prominent place in our annals. I have this day the privilege of declaring that the Malta Railway be open for public traffic. And in making this announcement I cannot but express the satisfaction which I derive from the reflection that this great work of public utility, but of private enterprise, has been commenced, and thus far brought to a successful termination, during the period of my Government of these Islands, and I desire to congratulate Mr. Geneste and those who have labored with him in attaining this end on the skill and perseverance with which they have carried out this work and overcome all the difficulties of their undertaking.

It is not necessary that I should detail to you those difficulties, since we can all somewhat appreciate their extent after seeing the vast terminus in Valetta and the numerous tunnels, all excavated in the solid rock, through which we have just passed. It is sufficient that I should observe that Mr. Geneste has brought us in safety, and with speed and comfort, from the very heart of the proud City of La Valetta to the foot of this the ancient capital of the Island, which is so rich in historic associations. And if the earliest founders of that capital could but look down upon this scene, I cannot but think of the amazement which they might feel in drawing a parallel between the rapid locomotion of modern science and the slow and painful traffic of past ages, of which we still see such interesting and mysterious records in the numerous cart ruts deeply cut in the solid rocks throughout this Island.

I have learnt with satisfaction that His Grace the Archbishop Bishop of this island has invoked the Divine Blessing on this great work; and I desire to add the expression of my earnest wish that it may prove as beneficial to the promoters as, I doubt not, it will eventually prove to be to the people. I say eventually, because I think we ought not to be too sanguine in our expectations. It appears to me probable that, for some time to come, so great a novelty may not be understood and appreciated as it deserves by a somewhat conservative people, who may perhaps be excused if they are slow to admit that the ways of their forefathers are capable of much improvement. I think therefore that many of those who may now be seen each evening streaming in hundreds from the gates of Valetta, in order to walk long distances to the homes which they left for their work in the morning, may still for a time, continue to do so, rather than expend a few pence in order to obtain speedier and less laborious means of transit. Eventually, however, I trust that they may learn the important truths that, to the industrious, time is money; and, by resorting to the Railway, tend to bring dividends to shareholders, whilst they consult their own interest.

In like manner, as regards goods traffic I think the people may be slow to commit to the Iron Horse the produce which they and their forefathers have, from time in memorial, been accustomed to bring, by night to the local markets, in their own carts and with their own cattle. When however the project of the originators of the Railway is carried out in its entirety; when this line is connected by branch lines with St. Paul’s Bay to the North and the different Casals on the South; then it will be, I think that a quicker pulse will beat through the island, and the advantages of Railway communication will force themselves on the people, as has been the case in all other countries in which railways have been introduced. Villas will arise on all sides to which those who are chained to their desks during the day in Valetta will be only too glad to resort, during the summer months, when their work is over in order to sleep in a more healthful atmosphere; and the value of property will be found to increase. I will not however further detain you nor add to the fatigue of your journey that of listening to a wearisome oration. This pleasing duty, alone remains to me of proposing that we should drink to the health of Mr. Geneste, the able and courteous manager of this line and the success and expansion of the Malta Railway.

Loud cheers followed His Excellency’s speech’ Mr. Geneste’s health and Prosperity to the Railway was drunk with three hearty hurrahs. Three cheers were then given for Mr. Geneste, who may well pride himself on the demonstration made him. The party then adjourned to the ground around, where the prospects of the Railway were hopefully discussed and Mr. Geneste was cordially congratulated on the success attending the undertaking. The scene presented to the view was most animated and picturesque, Citta Vecchia towering above Bengemina hills in the distance and the smiling plain beneath forming a most striking sight, enhanced by the circumstances of the day. Amidst cheers from the platform the train started on its return at 4 p.m. reaching town in 22 minutes.

Three cheers were then given on the platform for Mr. Geneste and H. E. the Governor. The company then slowly wended its way out, thoroughly satisfied and pleased with the entire proceedings. All the arrangements were carried out to perfection and nothing occurred to mar the harmony of the day which will long retain a green spot in the public memory. The success of the day will be an earnest for the future and PROSPERITY to the Malta Railway are our concluding words.

The Geneste question

The jubilant scenes that accompanied the opening belied a company in a parlous situation. They were saddled with substantial debts caused by the overspend in construction, and their legal issues continued. Directors had taken no wage in the first year and reduced their numbers to just three to further reduce costs. In this context, it’s perhaps unfair to hold Frank Geneste up as responsible for the company’s descent into bankruptcy, but his shortcomings as a manager no doubt contributed to the mess the railway found itself in.

As the railway opened to the public the day after the inauguration there was still an ebullient air around proceedings, customers taking the opportunity to be the first to ride this new novelty. The stations were crowded with eager passengers and the railway took £120. Geneste still enjoyed a certain celebrity, attending a gala dinner as guest of honour at the end of a successful first day’s traffic. He credited William Roebuck for his energetic and able management, without which the railway would not have opened. Diplomatically, he thanked his staff and contractors and was complementary of the Maltese and their hard work. Back in England Richard Gervaise Elwes went on record, saying “I would like to say a word on behalf of Mr Geneste. I have not always agreed with him, but I think that he has worked very hard and taken immense pains and has brought this concern to a satisfactory condition”. He hoped that Mr Geneste would continue to remain with the company.

The initial timetable used just a single train throughout the day. Strangely, the services started at Notabile at 5:13, meaning that an empty train would need to be dispatched from Hamrun to form it. There were seven more trains traversing the whole line throughout the day, and one early service between the capital and Hamrun. The train arriving at Notabile at 11:37 would have to idle there for one hour thirty-seven minutes before returning. Another peculiarity was the last train of the day ran non-stop between Notabile and Hamrun only, the railway closing at 8:06pm. Fares, approved by Government, weren’t cheap, passage the length of the line being 4 pence in third class, rising to 1 shilling for first. Return journeys for the same were 6 pence and one shilling six pence respectively. Even a short trip as far as Hamrun would set the customer back 2 pence. These might seem small sums by modern standards, but in Malta in 1883 these were unaffordable for must agricultural labourers.

Despite the prices, it was reported to the board in November that ladies felt unable to use the railway “the rush of third class passengers being so great”. Faced by the inundation by the working classes, numbers of first and second class customers had declined. The volume of third class traffic, however, had been unexpected, but didn’t offset the higher revenue lost from more expensive tickets.

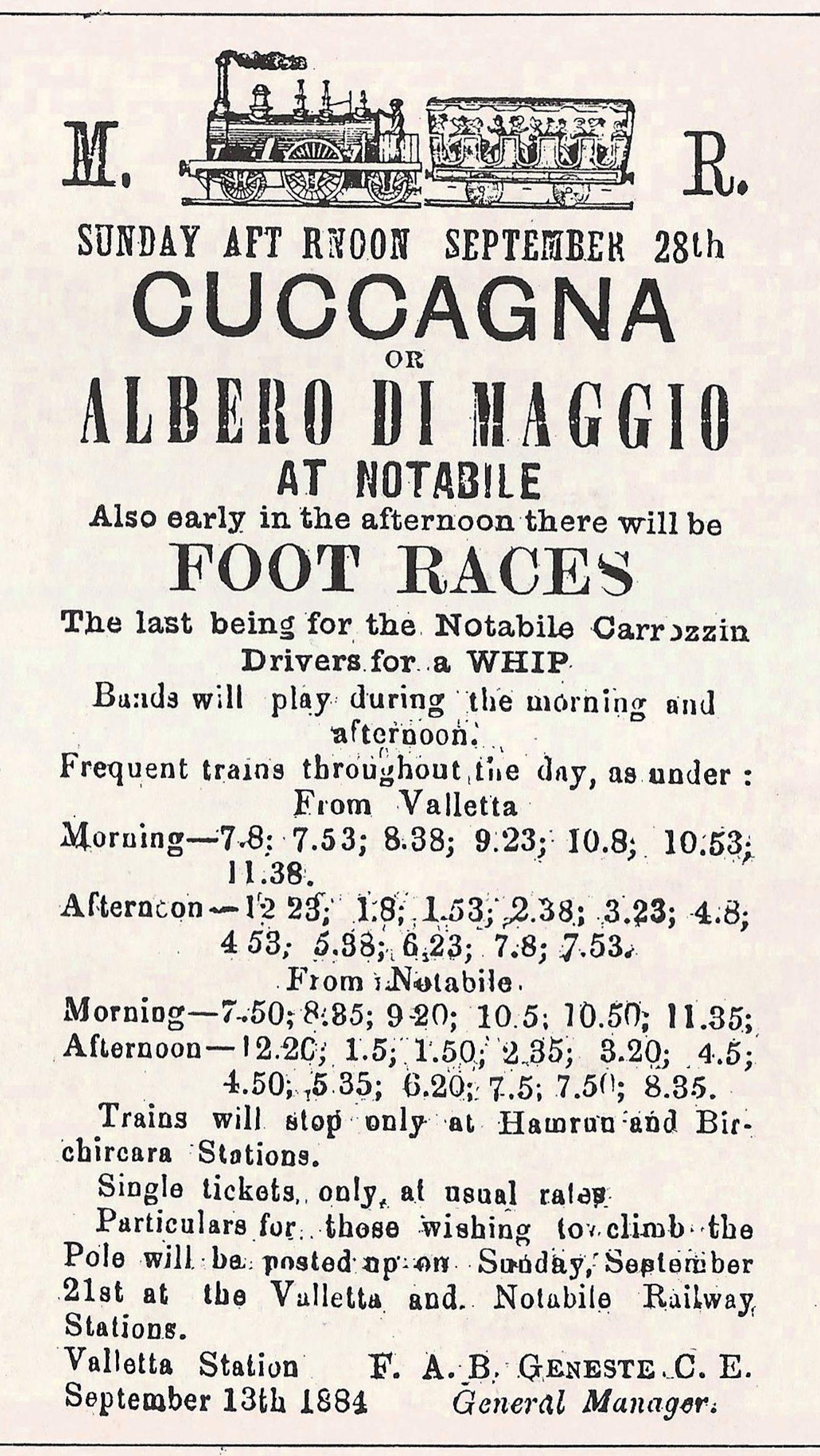

Genest soon discovered that the most profitable days were festa and race days, when trains out of Valletta were full and two engines were required to haul the heavy load. His efforts focussed on coaxing residents of the city on day-trips. To supplement the religious and horse-racing calendars, the railway took the opportunity to organise its own events, with special trains to carry the anticipated customers. The number of carriages available was not adequate to carry the number of travellers on these days, and the railway missed out on greater income because of it. Shareholders were informed at the AGM in November that the company had made arrangements to send out more rollingstock, no doubt at further expense, this having “been rendered absolutely necessary because it has been found that we could not carry the traffic which offered on certain festa days”. These carriages were expected to be in service by Christmas 1883.

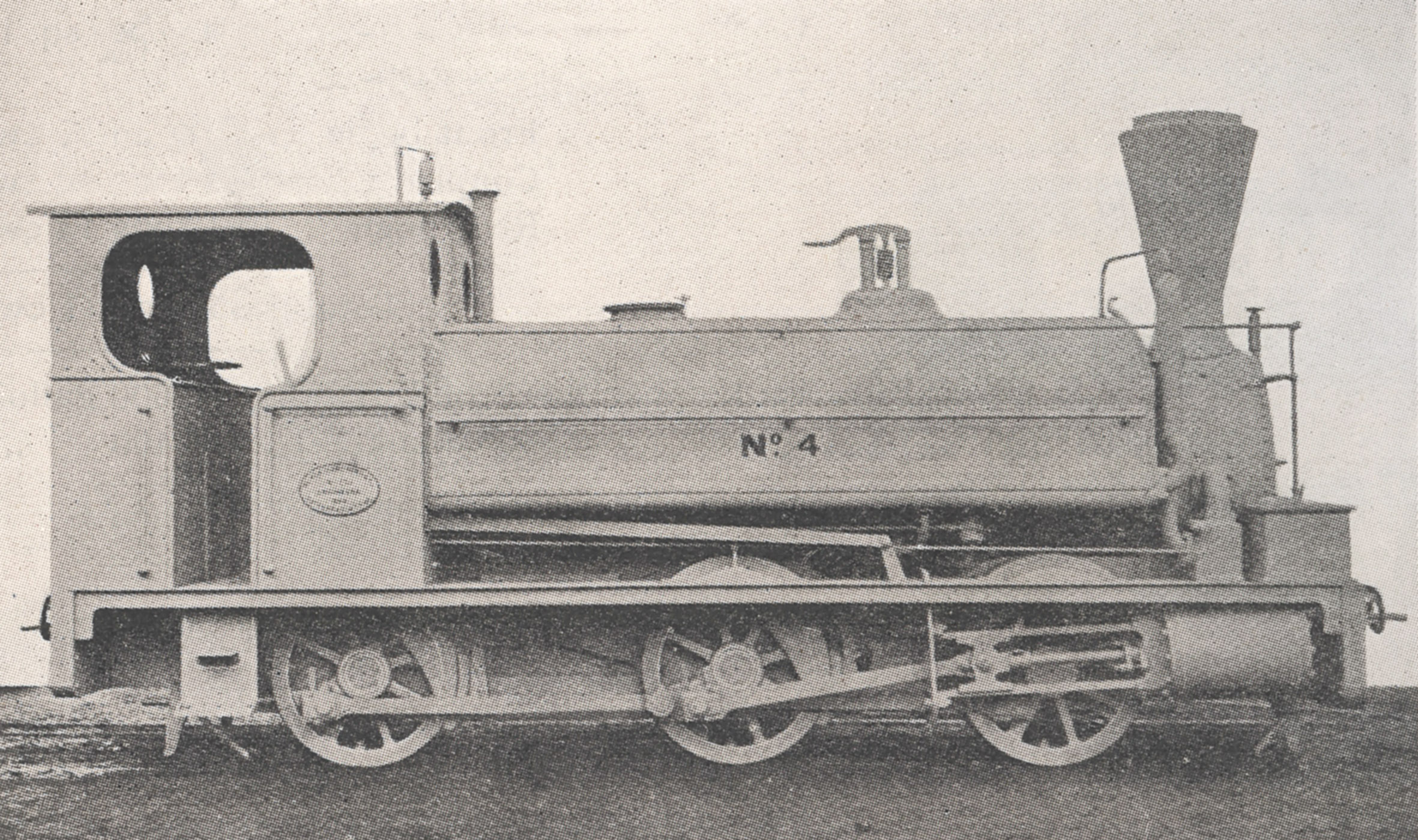

William Roebuck had ordered the engines in 1881 before he sanctioned a new location for Notabile station requiring a steeper ascent. The engines had been specified to run a regular daily service and not the longer and heavy trains that were needed to haul festival trains. Very quickly the company found itself forced to buy a heavier, more powerful, engine to address these problems; yet more expenditure. Engine No.4 arrived in Malta the following year to try and bolster the timetable on busier days, but quickly became the principal workhorse, leading to rapid and excessive wear.

The AGM also occasioned the announcement that the Mirabitas had been forced into the embarrassing position of having to apologise in writing to the railway company for having interrogated several shareholders in respect to their litigation and had been “running down” their investment. Their apology was circulated with the Chairman, Cavendish Taylor, bluntly telling investors they would “know what value to put upon such a person’s statements.”

At the same time, it was anticipated that residential traffic would increase; the attractions of the now-easily accessible hinterland would encourage an exodus out of Valletta to relocate into the countryside and commute. Rents quickly rose in Notabile in response to the railway’s arrival, and developers started building new houses to appeal to the colonial market. Coinciding with the railway’s opening, English-style villas at Saqqijja on the edge of Rabat were speedily erected to the designs of architect Andrea Vassallo, but the slow progress of development brought no quick relief to the railway.

Working expenses were 62% of receipts, higher than projected, but the railway had to support a large and expensive staff; meagre profits made little inroad into the debts despite the railway carrying around 500,000 passengers in its first year. A list of new by-laws published in 1885 suggest some of the problems Genest faced in protecting revenue. Travel on the line relied on a degree of trust. The stations being largely open in the English fashion, passengers could not always be trusted to buy their tickets before boarding the trains. The short time between stations and slow speeds were easily exploitable by ticket-dodgers joining and disembarking before the inspectors could pass through the train. Those who purchased tickets were abusing the conditions, upgrading themselves to first or second class carriages, not giving-up their ticket at the end of the journey and reusing them later, even altering them to appear valid for travel on another day, or deliberately continuing their journey beyond the destination they’d paid for.

It’s not clear how extensive these issues were or what impact they had on the line’s revenue, or how effective the new rules were in stemming the abuses, but they were virtually impossible to police on the festa days that the company were increasingly relying on to boost traffic. Around 7000 passengers could buy tickets to travel on these days, but how many more took advantage of the lax security at stations and large crowds to dodge fares isn’t clear. Trains were regularly overloaded, putting further pressure of the overworked locomotives.

Anniversary celebrations were organised in Rabat by Geneste, keen to repeat the financial boost experienced on high-days and holidays; Bands were hired, all manner of races put on, and a greasy-pig chase formed the highlight of proceedings. These events proved popular, but, after a few years of the balance books moving further into the red, they were discontinued. Maypole dancing and greasy-pole feasts were more of Geneste’s entrepreneurial enterprises to help drive traffic out of the capital. The increasingly unreliable steam engines also restricted his ambitions in this direction.

When the Government took over the railway in 1891 they found there to be no one considered capable of looking after the locos. Even if there had been, the tiny workshop at Hamrun had no facilities to undertake anything but minor works. For the original railway works, the cash-strapped company made the minimum possible investment, specifying the most basic track, locomotives, infrastructure and rollingstock to get the line up and running as economically as possible. Even the added weight of engine No.4 had damaged track so lightweight and flimsy that it distorted, and the longer more heavily-loaded trains stressed the infrastructure further.

Whether it was lack of money to properly maintain the railway, or negligence and inexperience on Geneste’s part, is a matter for debate. Despite the hard work he evidently invested in driving revenue, the absence of qualified expertise and the poor operation of the engines, and failure to ensure the permanent way was kept in order, suggest staff lacked appropriate skills, training, or supervision; for this, at least, Geneste should be held responsible as general manager. His focus on the heavy traffic to bring revenue was incompatible with the infrastructure and engineering at his disposal; another factor he should have been well aware of as an engineer, particularly one with such direct involvement in the railway’s construction. Coupled with his inability to execute his earlier contractual obligations to deliver the railway effectively, it’s easy to blame Geneste’s lack of experience in railway operation and general poor management for the railway’s troubles. Despite Government allegations he was running the railway to ruin, the company directors continued faith in him. His £760 per-annum wage was, though, perhaps money poorly spent.

Frank Geneste clearly felt aggrieved by claims he bore responsibility for the railway’s fast decline as, when his obituary was published in 1888, the tone taken around his time in Malta was at once laudatory and defensive. It claimed he carried out the construction of the railway “with complete success” and maintained and worked the line in “a masterly fashion”. In directing readers to local accounts of the different festas, “involving sudden and large traffic” and declaring “his (Geneste’s) pride being a clean bill”, the writer perhaps intimates and deflects attention from the Governmental attacks on his inability and performance.

Collapse and corruption

By the time Geneste left the company in 1887, the Malta Railway was in such a poor condition it could no longer maintain a reliable timetable. The Government complained to the company that he had breached the conditions of their concession by overcharging, failing to properly maintain the railway, locomotives and rollingstock, and cutting services. The engines were breaking down frequently and customers who had grown to depend on the line abandoned it, revenue falling as consequence. Geneste must have seen the proverbial writing on the wall. Perhaps pressure from Government or shareholders saw him pushed out or the accusations of mismanagement wore him down. He deeply resented the claims and is unlikely to have seen the fault as his own before packing his bags and leaving. Geneste resigned in November to take up the position of Resident Engineer and general Manager to the Santa Maria Railway in Columbia, where he died of typhus the following year.

His successor in Malta, a man called J. C. Gilbert, found the company is such dire financial straits and creditors on the island were circling. Eventually conditions became so bad that Government couldn’t avoid acting. In 1888, the Chief Engineer of the dockyard was invited to report on the condition of the locomotives for the railway Supervision Board. The findings were shocking. Engines No.1 and 3 were out of action with severely damaged boilers and that of No.2 needed repairs that would see it out of action for more than a month. Although No.4 was described as being in “fair” condition, it’s boiler exploded in Floriana tunnel on March 20 1889, the Supervision Board immediately banning the use of unsafe locomotives in the public interest. Number 1, by then only capable of working, though at reduced boiler pressure, was relied upon to limp-on with a basic service before even this too had to stop three weeks from April 18th for further repairs.

The Government chose to exercise its right under the terms of the concession to fine the company for the stoppage of services. Gilbert was unable to pay, as he’d “sent to London every available shilling for locomotive material”. On discovery that the company were unable to pay this or the dockyard’s bill to put engines 2 and 3 back in order (a sum just shy of £400) Government deferred the financial penalties. Instead, in the interest of getting the railway operational again, they paid for the engine repairs with the intention of re-billing the company for its outlay at a later date.

Although the company were clearly trying to reinstate services, and Government had given them the benefit of doubt, it soon became clear they had no money to continue operations. Faced with the inevitable, Government ordered the cessation of services on April 1st 1890. Four days later they declared the company had broken the conditions of their concession and desired to enact their right for the forfeiture of the railway in their favour. Protests and promises from the Company failed to convince, and the Government finally it took possession of the railway on 12th December 1890. The Investors were left with nothing but debts, and the company was formally declared bankrupt the following year.

Even as the railway struggled, what little money it was making was the subject of abuses by its own staff. An accountant employed by the company in Malta, 27 year-old Charles Dyer Belton, was bailed to appear in the country’s courts on April 29th 1889, charged with embezzling the substantial sum of £216 from the railway. Rather than face justice in Malta he stowed away on the ship “Palm” and, after his arrival at the port of Liverpool in May, gave himself up, confessing his crimes to local policeman. He was detained by a police court so that enquiries could be made. Extraordinarily, the company’s London solicitors, who confirmed Belton’s account, claimed the sum was “covered by a guarantee policy and it was not intended to prosecute the prisoner, who was therea discharged”!