Attard

4 miles, 8 chains – Journey time 15 mins

A garden station

By 1900 the Government had started the process of assembling land around the existing Attard station with a mind to expand it. There had long been complaints about the poor facilities and lack of shelter, critical letters appearing regularly in the press. However, it would be another decade before the project was complete.

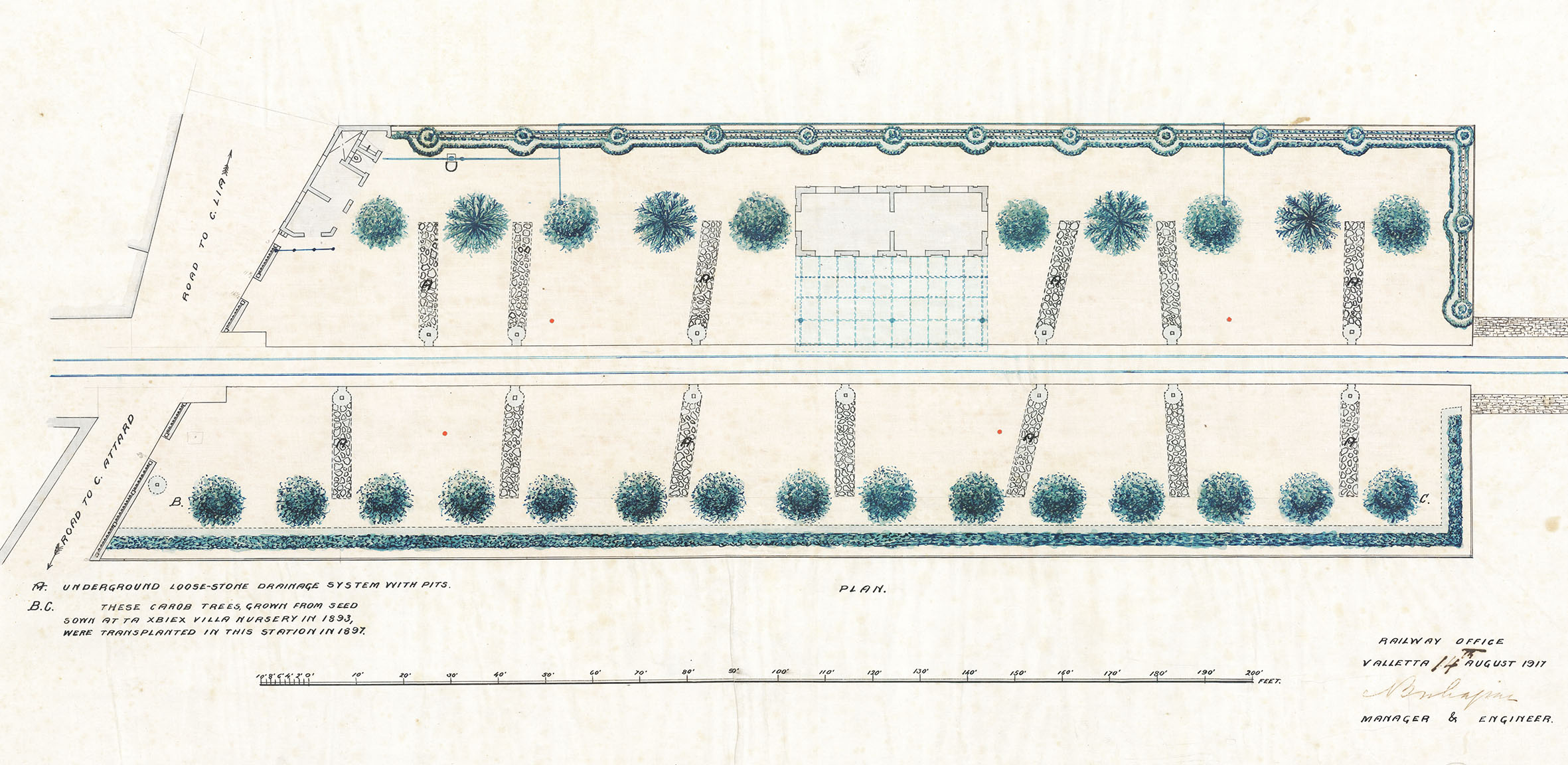

When Attard opened with the line in 1883, it was provided with a standard intermediate type building. This and the platform stood on the south side of the line, close to Casal Attard. The suburbs of the town began to attract government officials and the wealthy, keen to find a fashionable part of the island within convenient radius of Valletta, to build villas as summer residences. The railway, perhaps, had its part to play in Attard’s attraction, but, with increased traffic its poorly appointed station was soon an issue. Perhaps in an effort to create some additional shade for passengers, carob trees were planted along the platform in 1897, the occasion warranting its own cast iron plaque that still survives at the station site.

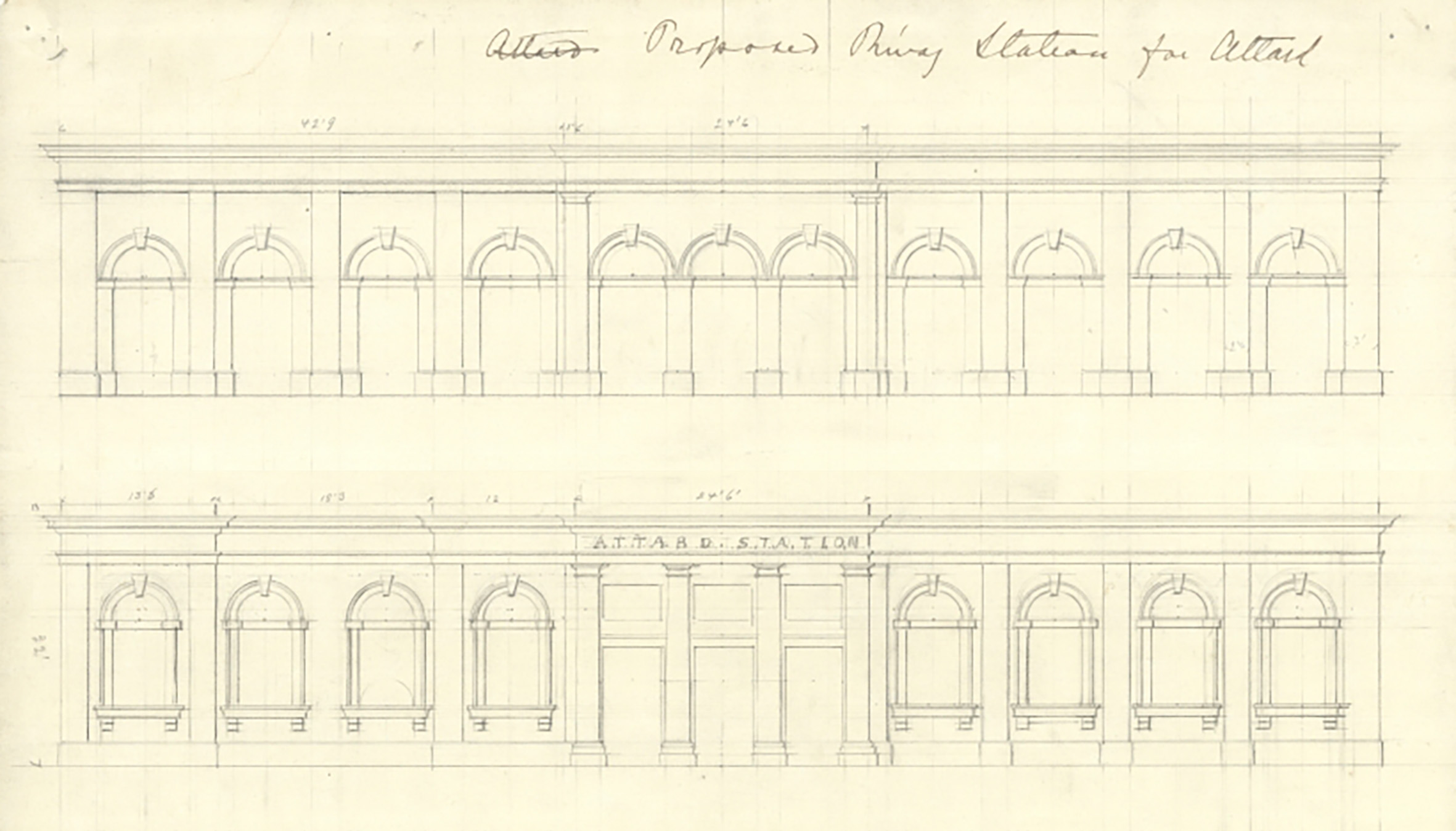

A crazily ambitious scheme was drawn up in 1904 for a new station building, one that might have rivalled Valletta in its size and architectural grandeur. This, however, was shelved and it would be a considerable time before the Railway officials returned to address the Attard problem.

Eventually, reconstruction works began in about 1909. Expanding the station wasn’t straightforward. Its location was at the end of one of the railways longest and tallest embankments, the topography around the existing station being problematic. To address this, a large podium needed to be created on both sides of the line to create a level base of sufficient size for the planned platforms, buildings, and gardens. The engineering works included arched and vaulted abutments around three sides to support the new base off which tall stone piers and railings defined the station boundary.

First and third class waiting rooms were provided in a smart new building with tall ceilings and a prodigiously proportioned station canopy, enough to satisfy any of the old station’s critics. The new building was sited on the north side of the track. The ticket office was provided in a separate building guarding the entrance to the platforms; this was a small building running parallel with the road, incorporating latrines and accommodation for the crossing keeper. A boundary of tall railings controlled access from the road on each side of the single track, a unique arrangement on the railway.

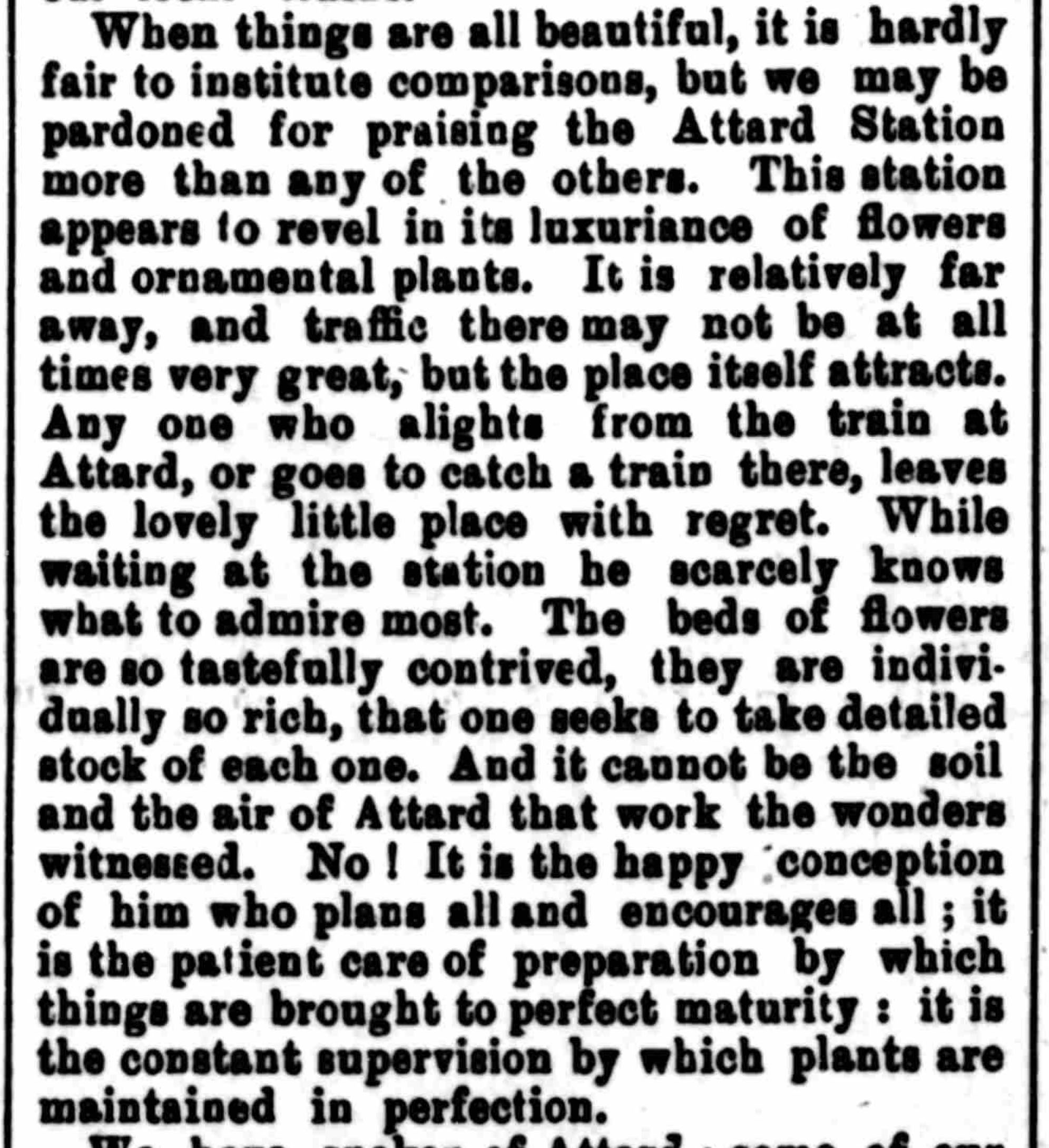

The new platforms were large, deep enough to accommodate even the biggest crowd arriving on local feast days. Like Birkirkara, rebuilt at the same time, tree pits and garden beds were incorporated into the designs from the start, to provide shade and surroundings so appealing they’d boost traffic in the face of competition. One author even praised Attard’s “improvements both structural and floral” above all the line’s other stations for its horticultural beauty, greater even than Birkirkara.

The rebuilt station served dutifully despite dwindling passenger numbers through the 1920s. A metal shelter (an inexplicable omission from the original designs) was added over the ticket office window, and a new block of latrines built at the back of the north platform, but little else changed here, until the unhappy occasion when the Railway closed on the last day of March 1931.

Remaining in Government ownership the building saw service again during WWII. It was converted for use as a ‘Victory Kitchen’ by the Communal Feeding Department, to tackle the severe food and fuel shortages that threatened starvation of the Island’s besieged populace. On 20th March 1942, the waiting room building that housed the newly created facility was damaged by a bomb and was subsequently demolished. Other structures survived longer; the ticket office stood still in the late 1960s, the latrines were later adapted for a sub-station.

The site, though, continued to offer attractive gardens, eventually being formalised as a park. More recently, the park was chosen as the location for a new local library. After intervention by the Malta Railway Foundation the incongruous original design was redrawn as a near-replica of the original waiting room building: a happy conclusion. This has also been accompanied by a remarkable life-size recreation of one of the railway locomotives made entirely of corrugated cardboard by Stephen Bonello. It stands in a purpose-built shelter on the alignment of the old track bed.

Previous Station / Next Station