VALLETTA

0 miles, 0 chains – Journey time 0 mins

Capital terminus

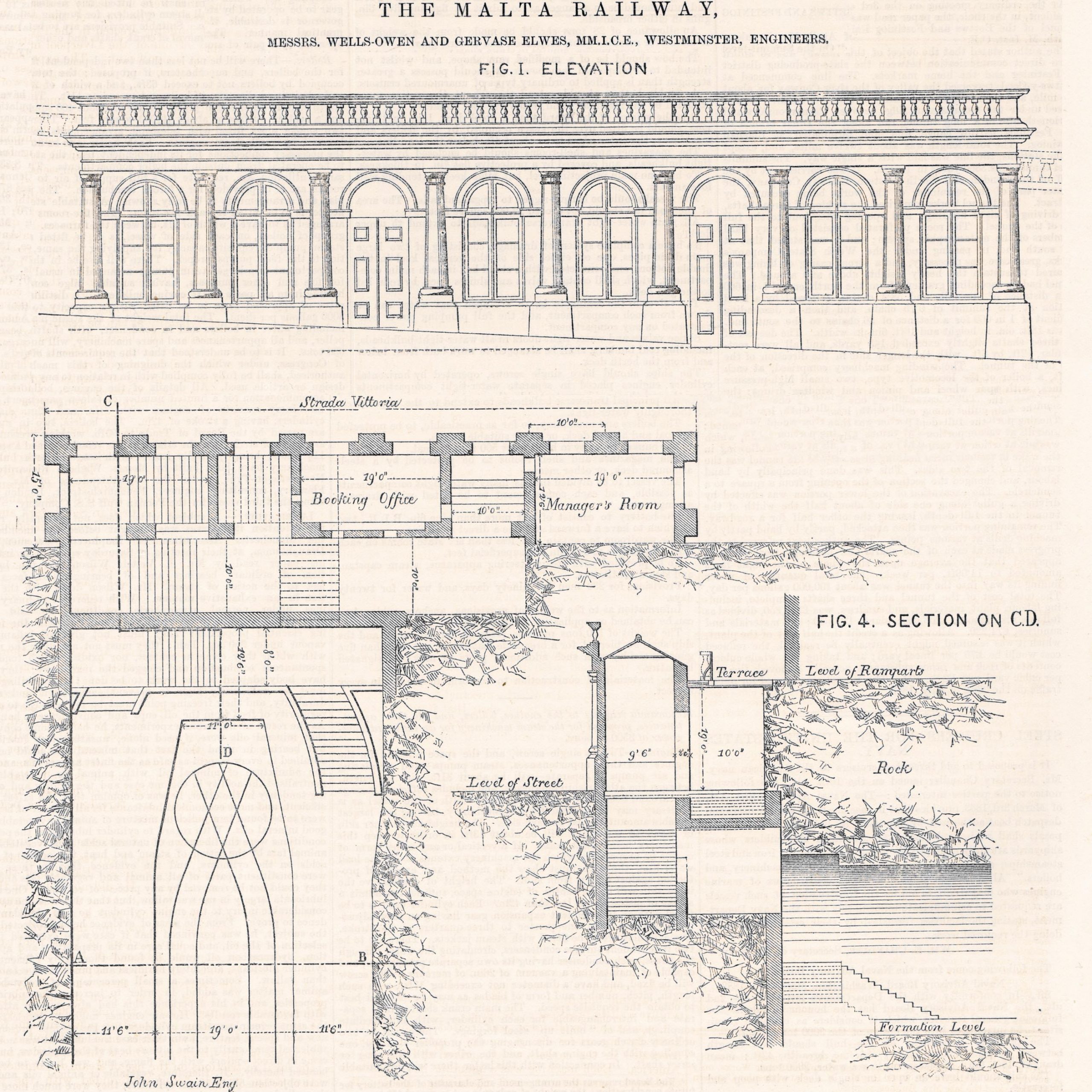

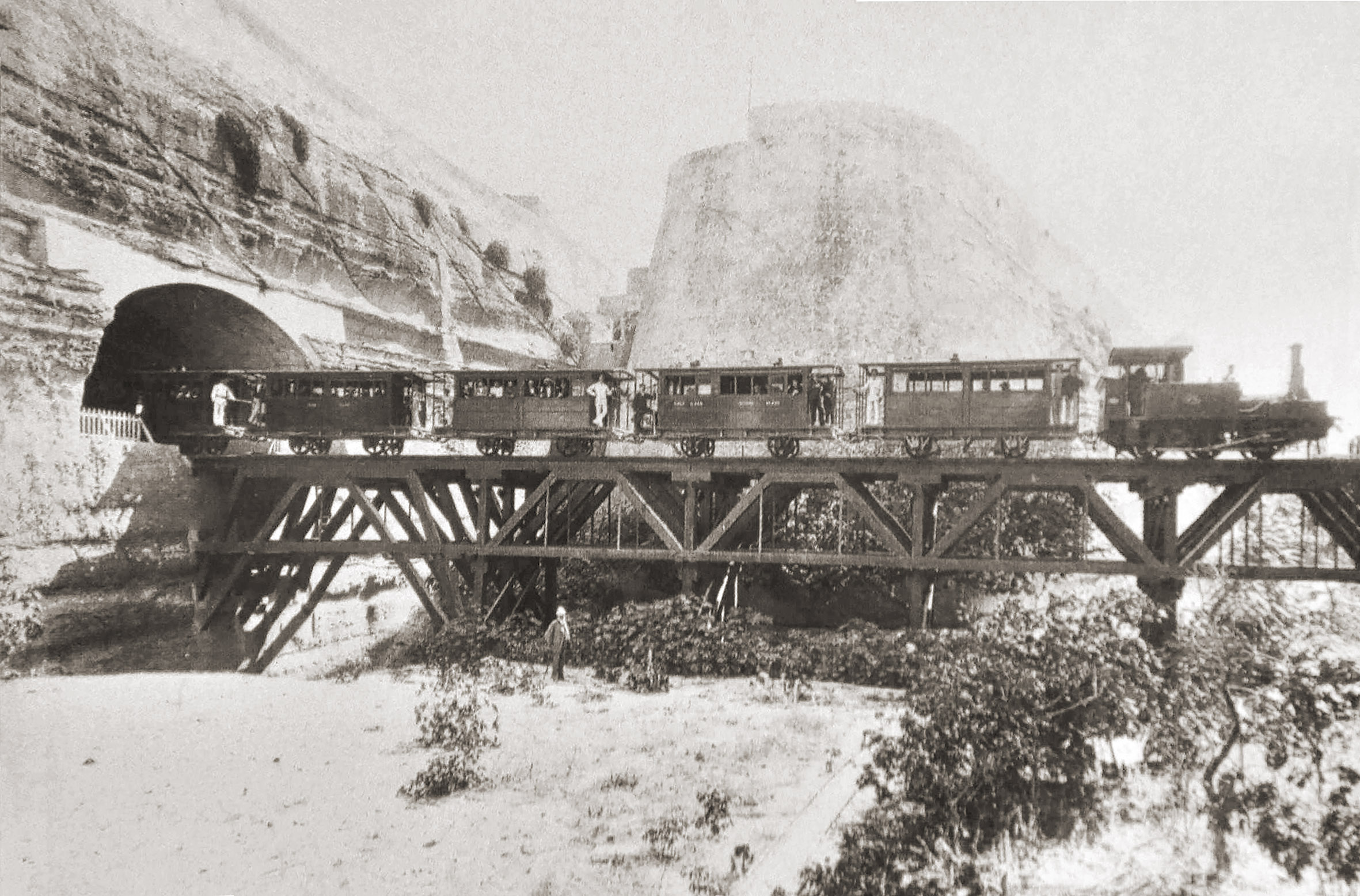

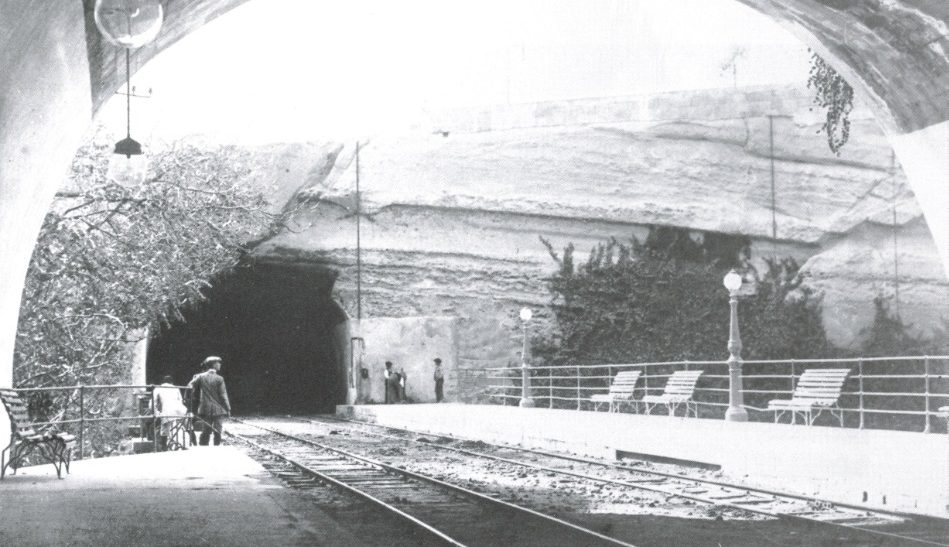

As initially built, the capital’s station was an odd paradox; superficially grand and elegant outside, but internally dark, smoky, and cramped. At street level the handsome stone building was bedecked with arcades, columns, and classical detailing, fit as the headquarters of the railway company but also a suitable partner to the ostentatious Royal Opera House directly opposite. Immediately and deep below this, accessed by a narrow underground passage with innumerable steps and hardly space for two people to pass, was a wide tunnel that accommodated the platforms and track. The furthest end of the tunnel opened precipitously out over the city’s main ditch where a wooden trestle bridge took trains briefly into the sun before plunging again into the tunnel beneath Floriana.

Siting a railway station underground was hardly ideal and very costly, but with few suitable sites in Valletta, and the British military placing strict orders to preserve the city’s defensive strength, a compromise was necessary. Underground stations were already commonplace in London, but the company’s engineers, Wells-Owen & Elwes, had scant experience in underground railways and rarely visited during construction. Earlier designs for the station had been more ambitious, with two staircases and a larger building, but the Malta Railway Company was already struggling financially, and many shortcuts were made.

There were two entrances to the street, possibly separating the passengers by class, or operating as a dedicated entrance and exit to ease overcrowding. Both doors led past a booking office where tickets were issued through small windows. Behind this a long top-lit passage ran the length of the building, eventually leading passengers into an arcaded hall through which stone steps descended to the trains. The only other room, at the far end of the terminus building, was allocated to the railway manager.

The wide vault of the station was dug out of the solid rock progressively between December 1881 and May the following year. The station was long enough only for a locomotive and six carriages. Early drawings show what looks to be a turntable, likely to have been a sector plate that allowed engines to be switched between tracks rather than to turn them entirely. There was a similar structure designed for Notabile station at Rabat. With limited space at both ends of the line station these would have avoided the need for tradditional points and a head-shunt, saving many precious yards of platform for carriages. Initially there was no ventilation in the tunnel, and the location of the pedestrian passage and steps at the very end of the tracks would have resulted in smoke being drawn through the passenger tunnel and up into the terminus building itself.

When the line opened on 28th February 1883, little mention was made of the new station, but its shortcomings must have been quickly felt, particularly on busy feast days when crowds hustled through the narrow stairs and the short trains were overloaded with passengers. It’s perhaps unsurprising then, that, when the Government took over the railway in 1891, they quickly sought to alter the building, tunnel, and access to increase capacity and passenger comfort.

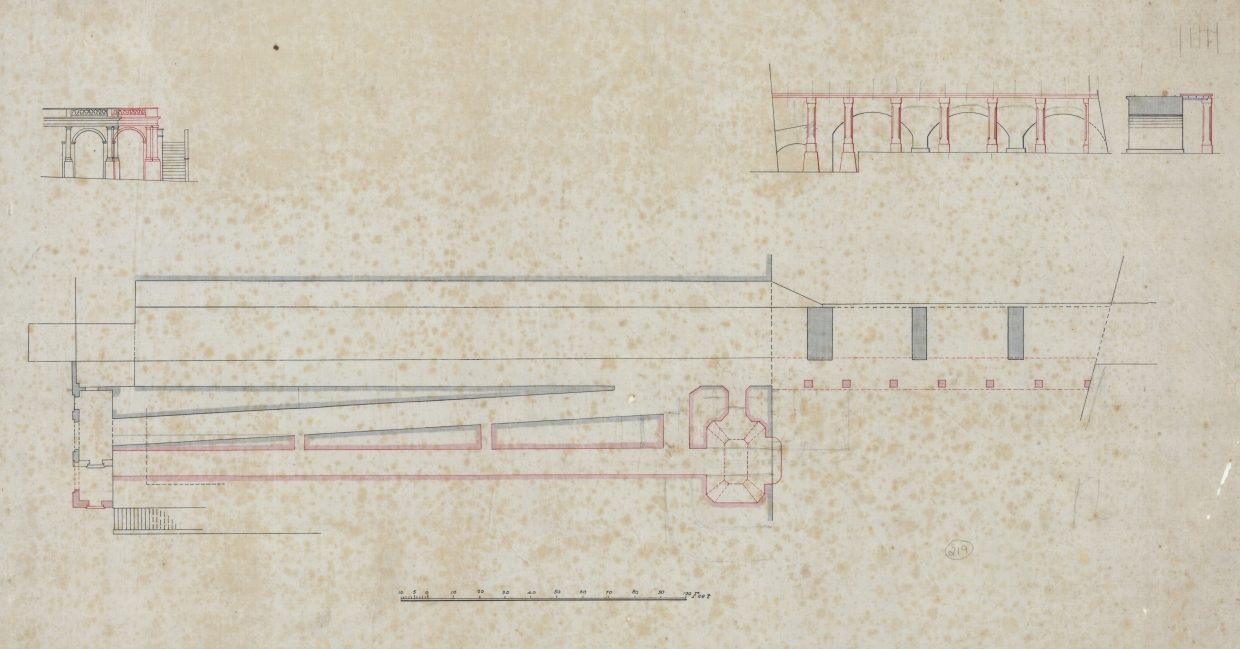

The Government’s first priority was the replacement of the bridge at the entrance to the station with one of stone. The old one, made of timber at the insistence of the military, had decayed and become unsafe. The new stone structure was wider, allowing more space to extend platforms into the daylight and accommodate longer trains. The sector plate, too small for the newly purchased locomotive No.5, was replaced with a more reliable arrangement of points by 1892. In 1894 work began cutting a new ramped passage between the street and platform levels; the original staircase down was converted into a much-needed ventilation shaft and its removal at platform level allowed for the extension of the tunnel for shunting and a siding.

At street level the terminus building was extended by one bay, a wider arched opening with metal concertina gates introduced and a well-lit hall created at the head of the new ramp. Rooms in the existing building freed-up by the alterations allowed the expansion of the railway offices. Tracks in the station underwent several incremental extensions further under the city allowing for more carriages and improved operation. Opening in 1898, a second ramp increased capacity further, and created new public access to new footpaths laid the ditch between Marsamuscetto and the Custom house; passengers could now approach directly from the quayside and the ferry. At the same time the station building was extended by a further bay. At last, by the turn of the 20th Century and with significant investment, Valletta had a station adequate for its needs.

For the next three decades visitors passing through the Porta Reale had a grandstand view of the comings-and-goings of the trains below. Over the years they would have witnessed the gradual increase in passenger numbers waiting on the platform before their slow decline as at first the tram and then the bus stole business. In the final months only a limited timetable was in operation, before trains disappeared entirely from the scene at the end of March 1931, never to return.

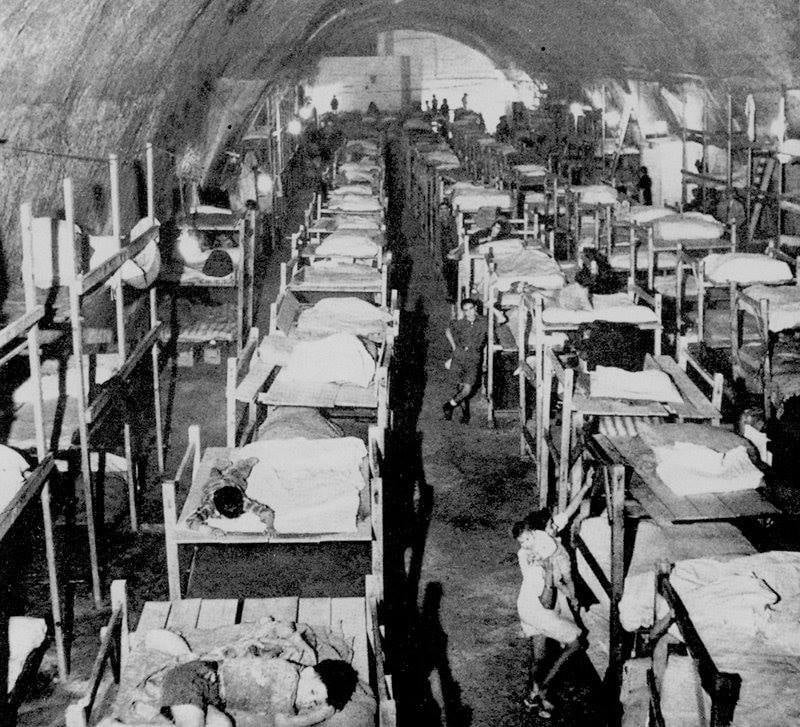

After closure the station buildings were repurposed for other government uses and small shops, the ramp down to the ditch remaining open to the public. The station tunnel was next used as an air raid shelter during WWII and the Siege of Malta, having its arch infilled with blast walls, and latrines and washrooms erected on the bridge. After the war several plans for a bus station and mushroom farm evaporated. Many will still remember the Yellow Garage that took on the lease of the station tunnel until redevelopment for the new Maltese Parliament buildings in 2013, when the tunnel was emptied and repurposed for Government archives. Much work was done at that time to restore and conserve the surviving bridge and station features.

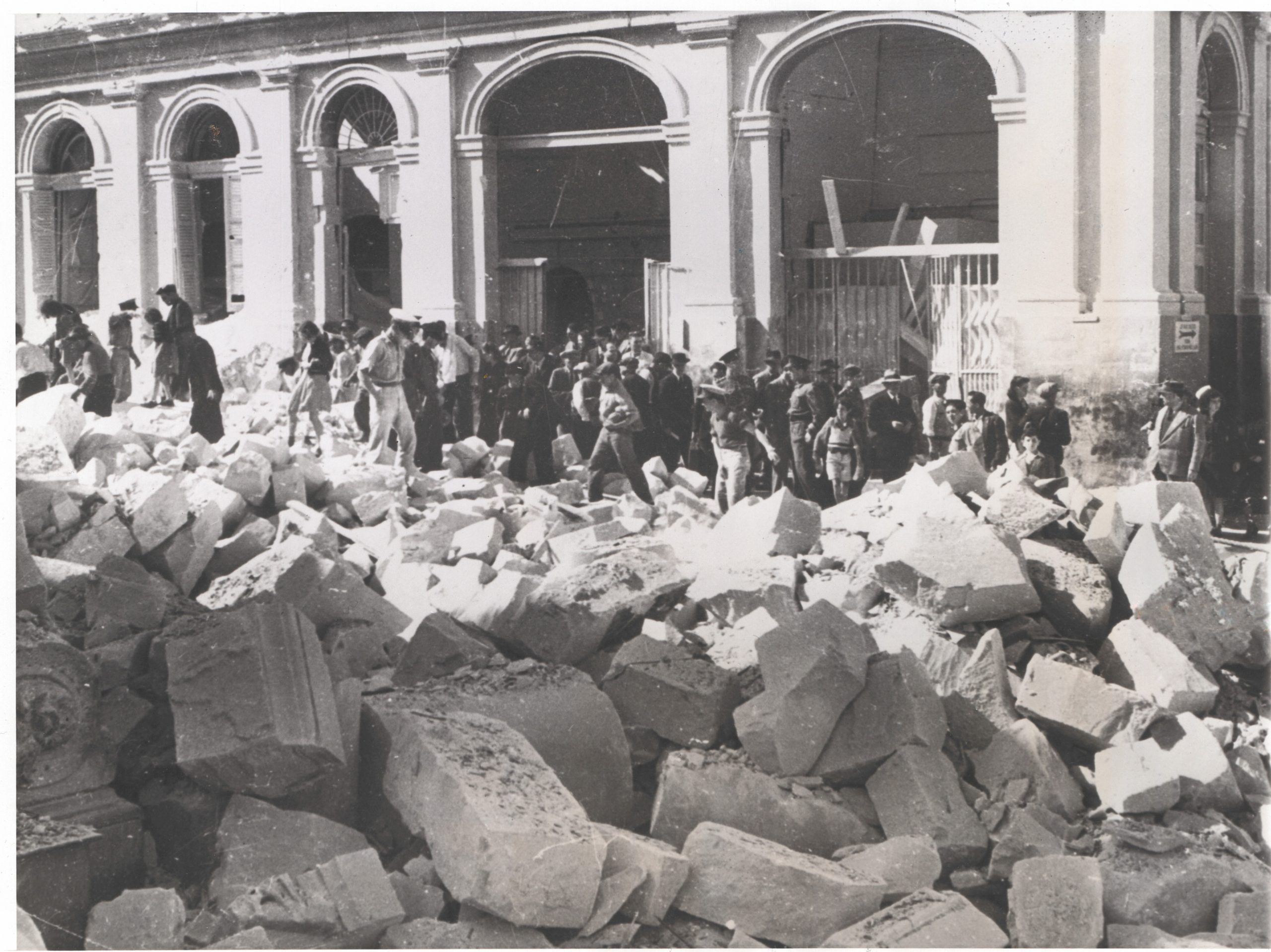

The handsome station building at street level fared less well. Although it was badly damaged by bombing during the war it was patched-up and continued in use, unlike the Royal Opera House opposite that had a less fortunate end. The building eventually succumbed to the town planner, being obliterated to make way for Freedom Square in 1963.

Next station