A modern public service: 1890-1910

Government salvation

In 1890 the colonial government of Malta found itself the owner of a beaten-up and run-down railway line, with no fully functioning engines and its infrastructure in a dire state. It would likely prove impossible to find a private investor to take interest in the railway, but Government already had it in mind to run it itself. There was, however, a great deal of work before that could happen. The railway equipment was described as being “strained to it utmost” and that “there seems to be no one capable of looking after the locos”. On top of this, the wooden railway bridge outside Valletta station had been declared unsafe and needing replacement as well as a lengthy list of other maintenance problems.

It was clearly going to cost a substantial sum to return to operation, but Gerald Strickland (1861-1940), one of the eight native Maltese elected to the Council of Government and its Chief Secretary from 1888, had every confidence that the line was an essential public service that should be supported. At just 25 years of age, he had the energy and drive needed to take on the challenge. Whilst the conditions of the original concession to the company allowed for the forfeiting of the line itself, it didn’t cover the engines and rollingstock required to operate it; Although they were badly worn-out, the purchase of these vehicles would be essential to restart services. The company’s creditors had already secured consent to have everything auctioned. Strickland ensured that the Government was the winning bidder, likely paying little more than scrap value for most of it. Some of what was paid ended up coming back to them, a court claim against the company, for costs incurred, being resolved in their favour for £584.

Costs to repair and reopen the line were estimated at £8000 and would take significant time to complete. All this time, the Maltese public would be without the benefits of the railway. This time would, at least, allow for the railway to be reorganised on a sustainable model. It was intended to operate as an independent social enterprise, run as a business in the public interest with all surplus profits reinvested back into the operation. It was required to stand on its own feet and not prove a burden to the taxpayer. The Engineer and General Manager would be a direct Government appointment. Loans were granted by the Council of Government to cover the cost of reopening, debts the railway was expected to pay off over time.

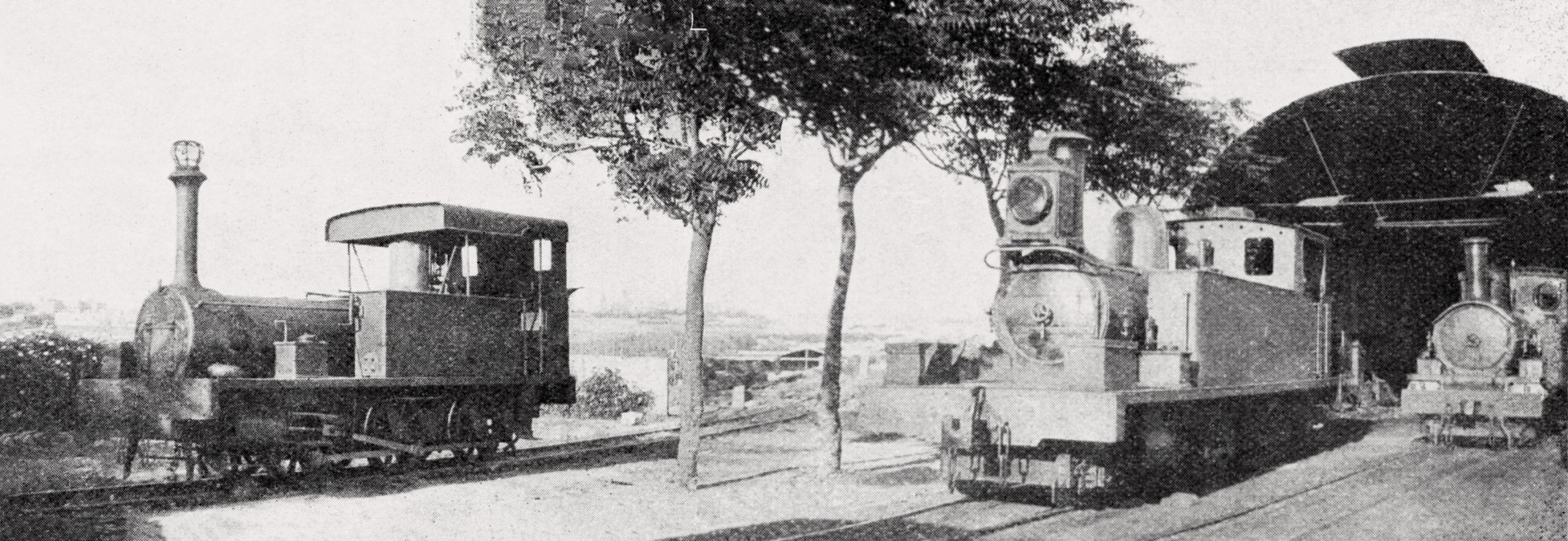

Learning from the experience of the private company, it was clear that to make money trains would need to run more effectively. Reducing fares to be more affordable would encourage passengers, and adapting the railway to run longer, more efficient, trains with greater capacity was key to success. This would require more capable and powerful engines, somewhere to maintain them properly, and the upgrading of the infrastructure. Ordered again from Manning Wardle, locomotive No.5 was a significant upgrade on their first three engines for the railway. The recommencement of services was delayed until it could be shipped to the island, arriving in late in 1891 in adequate time to be tested and train crew familiarised before the opening scheduled for January 1892.

Recognising the lack of adequate maintenance facilities available at Hamrun, it was decided that new workshops should be built to remove the railway’s dependence on the dockyard for repairs. It would need to be well equipped with modern tools and with trained staff capable of overhauling the engines. Apprenticeships would be created so that the next generation could gain engineering experience that might benefit the railway, and Malta more generally, into future; this would later expand into the technical school that turned out many hundreds of capable students.

After the Council of Government settled on the final organisational structure for the railway, in November 1891, Lorenzo Gatt was appointed Engineer and General Manager, and Nicola Buhagiar as assistant in the role. Initially, it seems, Gatt was only the interim manager, but performed to such a high standard that he was given the role formally in 1894. Gatt’s annual wage was £180 though later raised to £300; this paled in comparison with Geneste’s earlier remuneration of an incredible £760 for the same position. Gatt had entered Government as a Land surveyor and architect in the Public Works Department before being appointed as Railway Inspector in 1884, so would have had detailed knowledge of the line. Buhagiar was also drawn from the same office and also described as an architect and land surveyor. The engagement of these men secured for Strickland the capable, competent, and committed management he needed to rebuild the railway and develop it for the future.

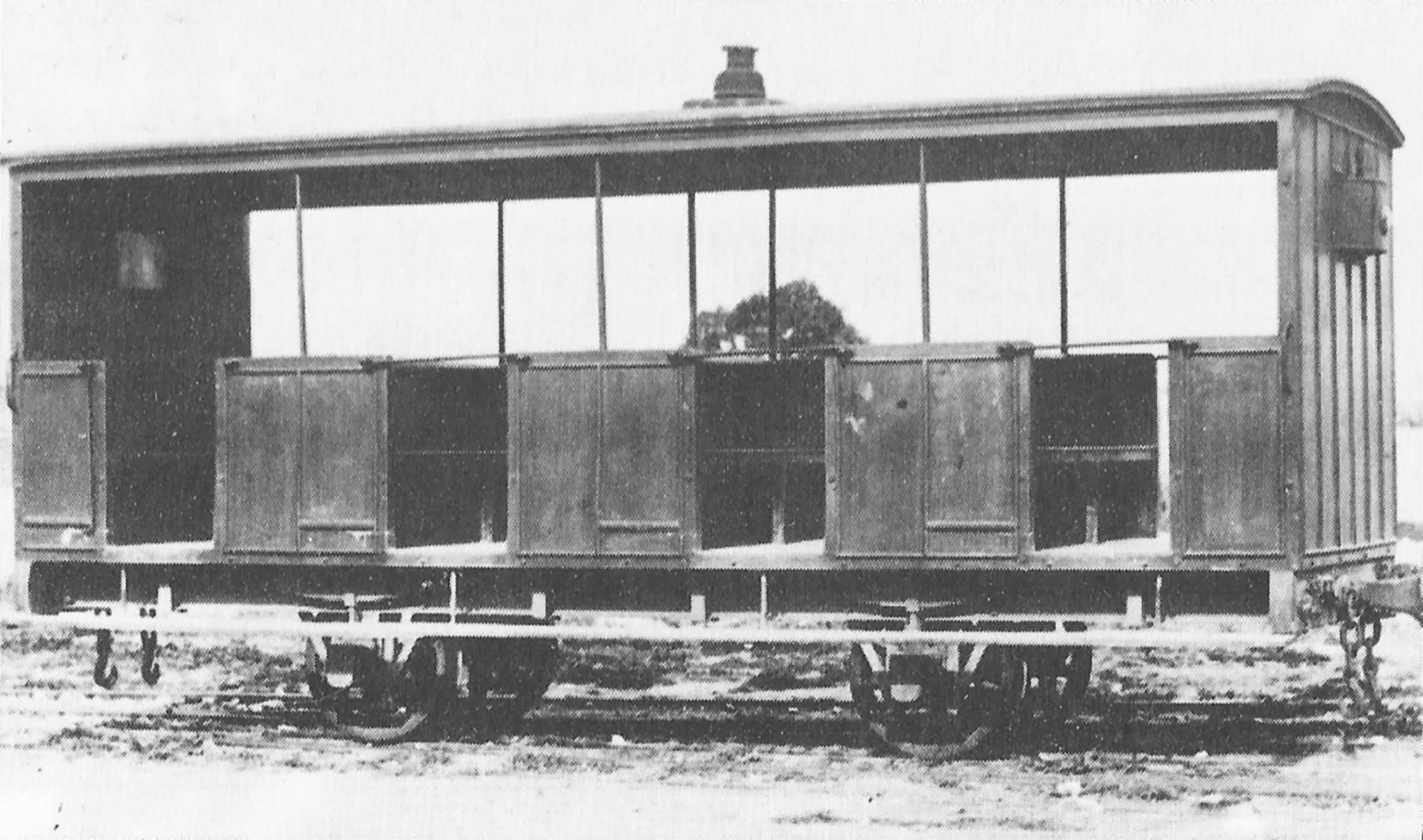

The older locomotives were brought back into operational condition and new rules introduced to instruct two engines would be used to haul trains on days of exceptionally heavy traffic, avoiding the impact of overtaxing them. These same rules set service requirements, the minimum being a timetable requiring two trains in daily operation. Fares between the two termini were set at 6 pence for First class and tuppence for third; only single tickets would be sold. Second class was also jettisoned in favour of greater capacity in the other classes, particularly in third class. Additional trains were to be laid-on for the carriage of workmen at economy-fares. A series of new instructions were issued to protect revenue, tightening the sale, use, and collection of tickets, in an effort to reduce abuse and fraud. As part of this effort, changes were made in the layout of stations, with boundary walls built to increase control over passengers and reduce the likelihood of fare evasion.

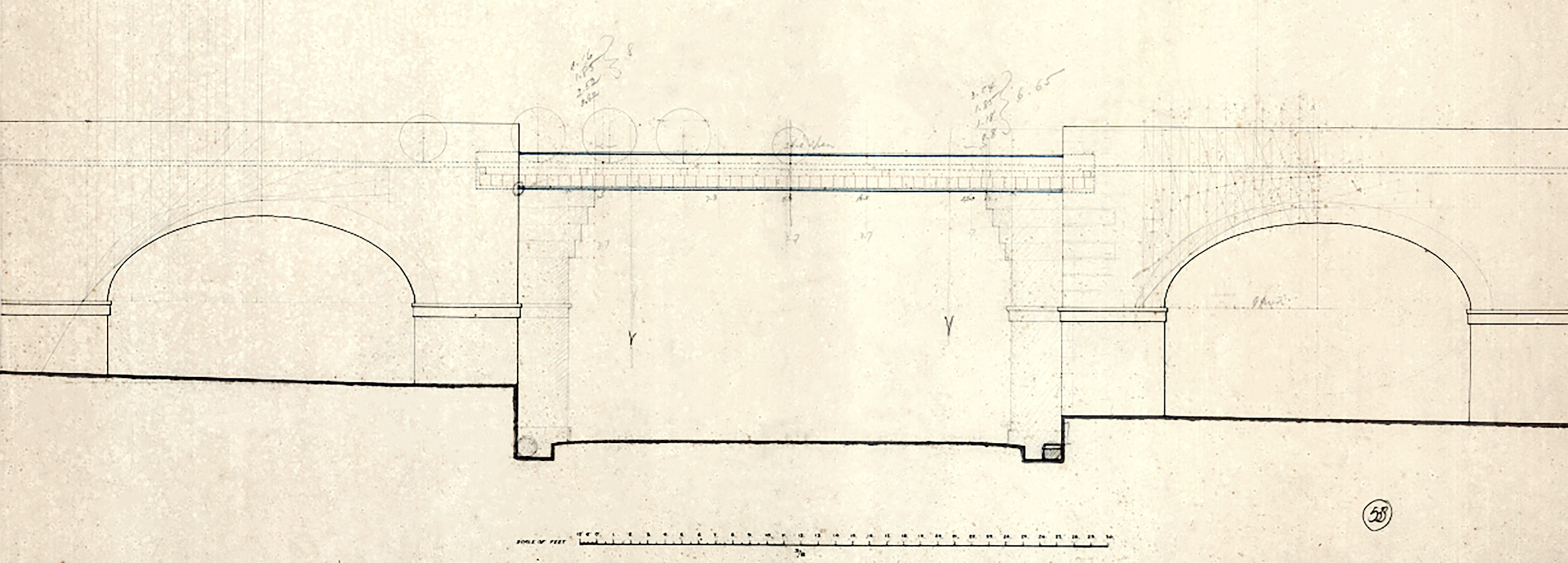

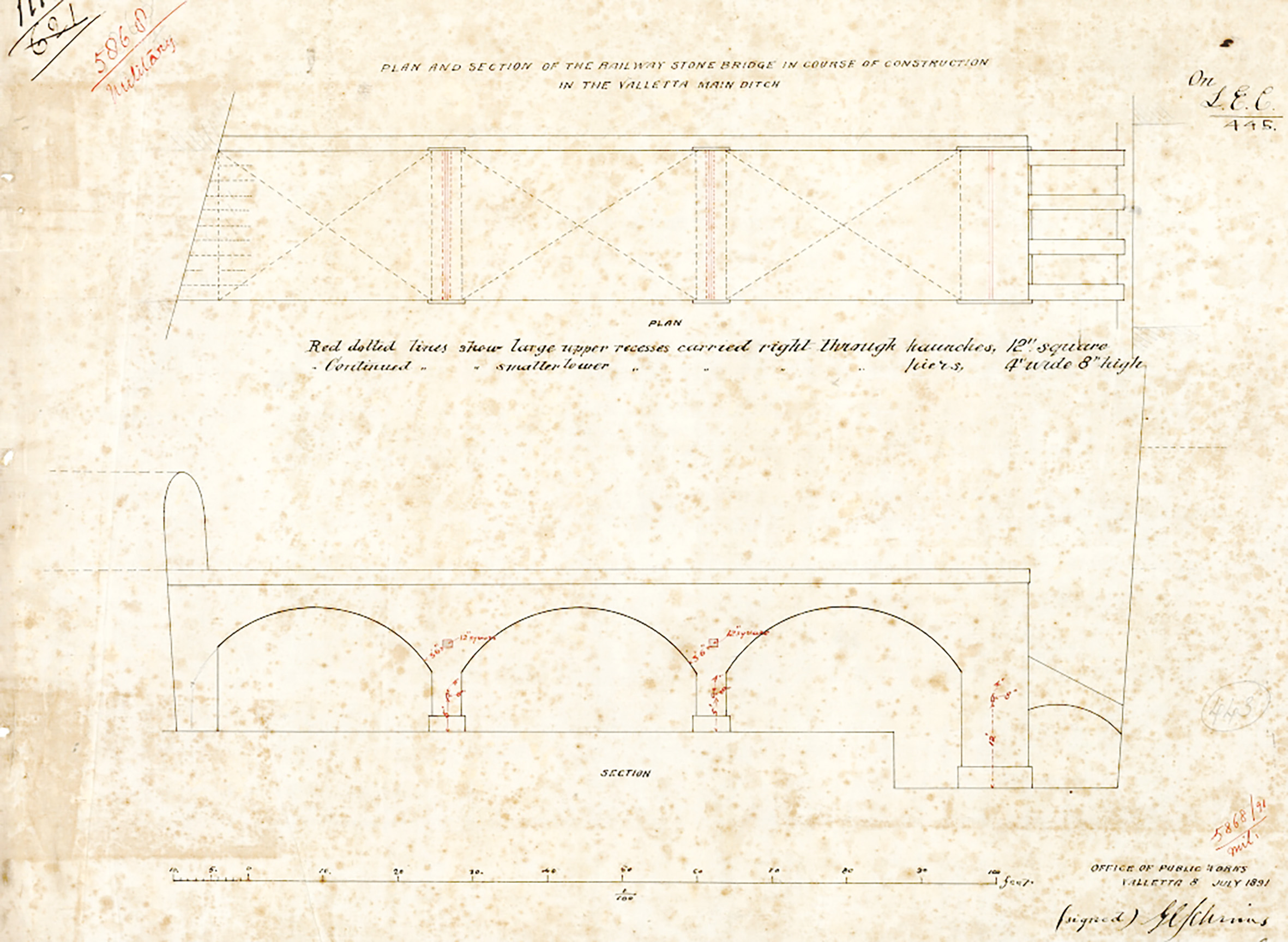

On the line, £751 was an unavoidable cost in replacing the rotten bridge at Valletta and construction of a new stone structure; It was sharp work to have this constructed in less than eight months. The timber bridge near Porte des Bombes was also found to be unsafe, temporary props under the main trusses being considered an adequate temporary measure. Princess Melita Road bridge was reinforced with new stonework to carry the heavier trains and address deflection in the existing arches. As well as new rails, the permanent way needed the removal of an astonishing 1,200 cheap un-creosoted pine sleepers and their replacement in more substantial oak, symptomatic of the financial shortcuts taken in its original construction. Eventually, after 22 months closure, everything was sufficiently advanced to restart public railway services on 25th January 1892.

Back on Track: Resurrection under Lorenzo Gatt

Lorenzo Gatt was in position as General Manager for just four years, but his efforts during this time put the railway back on a level footing, passengers returned, and the railway began to make a profit. Public reaction to Government’s intervention was a mixture of general relief and approval. There was admiration for the work undertaken and the resolve shown in providing a genuine public service.

The railway was put back in good order before it reopened early in 1892, but this wouldn’t be the end of improvements. Within a matter of weeks of the railway reopening, Gatt returned to Strickland with a list of urgent items that needed attending to. These were a mix of measures designed to protect revenue, improve facilities, and increase services. Valletta station needed alterations to allow larger locomotives to use it, including the reconfiguration of the steps down from street level.

Hamrun was the focus of a number of proposals for the provision of new engineering facilities to maintain engines and rolling stock. New equipment was bought and basic carriage sheds erected along the southern boundary. Engine sheds were also to be built; it’s possible that these were the first portions of the engineering works, as the locomotives are only known to have been stabled in the old carriage shed in later years. A new engineering school was inaugurated here, Gatt stating that “the object of this school in connection with the Railway, is to lay the foundation of a practical system of technical instruction in a manner which will turn the railway workshop to the best and most economical advantage.”

At the same time urgent works were sanctioned to increase safety and security at Notabile before the crowds expected for L-Imnarja in June. Chaotic scenes had arisen under Geneste’s time managing the railway, with trains and platforms dangerously overloaded, and widespread abuse of ticketing regulations and staff. Steel railings and walls were built around the entire station precinct with strict controls introduced at the level of Racecourse Road to ensure capacity wasn’t exceeded.

Gatt presented another list of recommendations in February 1893 after the first year of Government control with a yet more ambitious programme of works. Two new engines were asked for, on top of No.5 and 6 already bought, though the railway would have to wait until 1895 before the first was delivered. Eight of the twelve proposals focussed on improvement of stations. The construction of boundary walls around Birkirkara and Hamrun and ticket offices to control access to platforms sought to reduce fare-dodging. That at Hamrun was a prominent structure facing directly up Station Road, giving the railway a much more prominent presence.

Valletta was to receive extended tunnels eastwards under the city, and in the direction of Floriana to increase capacity. Though not included specifically, the alterations here would include a new ramped tunnel to replace the old steps down to the platforms and required an extension and reconfiguration of the station building. Floriana station was to be rebuilt on a new site, in a cutting to be made into the tunnel near Argotti gardens with ramps down to access it. At Notabile, a new latrine was built on Racecourse Road for the convenience of passengers and cabmen, and two “verandas” were planned to give shelter to passengers waiting to enter the station.

The most substantial project Gatt included in his 1893 report was the extension of the railway under Mdina and the building of a new station. The idea was originally mooted to create a tunnel long enough for the storage of the carriages required for the early-morning workmen’s train but soon expanded to include a new underground station at Greeks gate, accessed by a ramp. In 1895, the sum of £5000 was budgeted for the necessary tunnelling, but this was later to develop into a much more ambitious project.

One less successful project was the reconstruction of Birkirkara station. By 1894 this had grown in scope well beyond the intended boundary walls and ticket office, and into a grandiose plan to relocate the whole station to the east side of Fleur de Lys Road, create a civic centre with post office and court house, and dig beneath the railway to take the main road beneath it, removing the need for a level crossing. Government considered the costs, £1,200, too great and withdrew support for the project in 1899, the same sum already having been expended on the work.

By the time Gatt took a new job with Joint Department of Electric Light and Water Works, in December 1895, through a great deal of hard work, he’d secured a future for the railway. It was described by the Lieutenant Governor as “an unprecedented success”. The line was now profitable, it had ambitious plans for extending to Mtarfa, and the first of a new batch of locomotives, No.7, had just been delivered. However, it would be his successor, Nicola Buhagiar, who would take the railway forward into its golden age

Blossoming Under Buhagiar

With a background in architecture, it’s perhaps unsurprising that, under Nicola Buhagiar’s management, the railway’s buildings and appearance was transformed. It looks likely that he was directly responsible for many of the designs and the familiar appearance of surviving stations at Hamrun, Birkirkara, and Museum. He is also credited with the transformation of the station platforms into beautiful gardens. Whilst his predecessor relied on the Office of Public Works to provide drawings for the railway, those produced after 1895 are initialled only by Buhagiar or issued from the Railway Office.

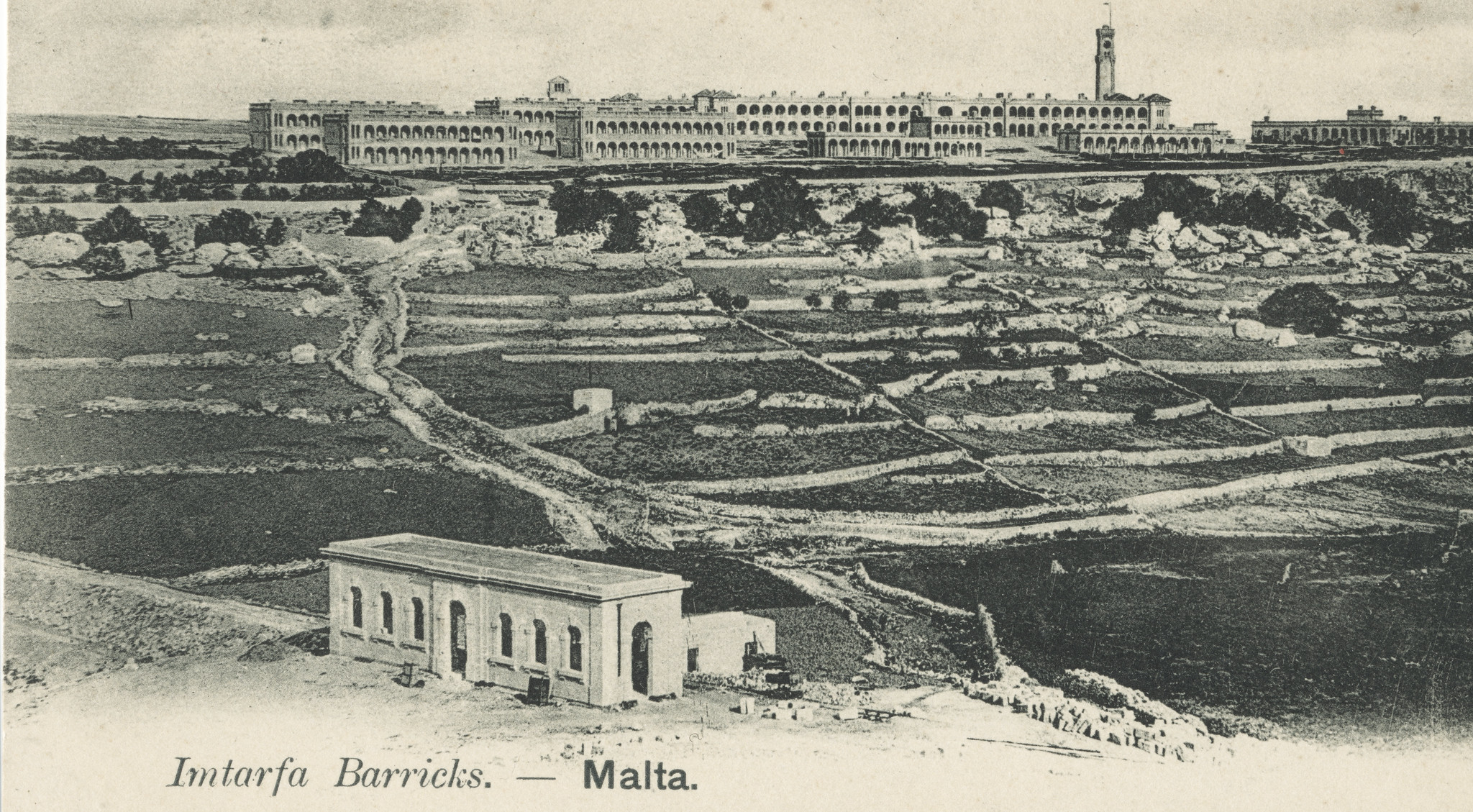

On his appointment Buhagiar inherited the project to extend the railway to a new station dug beneath Mdina. In 1896, when 600 feet of tunnel had already commenced, the question was asked: Why not extend it further? For the railway, the new barracks being built by the British Army at Mtarfa represented a tantalising opportunity to increase revenue. Construction on these had began in 1893, and in 1896 they were about to receive their first troops when Local Government granted Buhagiar the sum of £15,000, a loan from the British Government, to extend the railway further to the other side of Mdina.

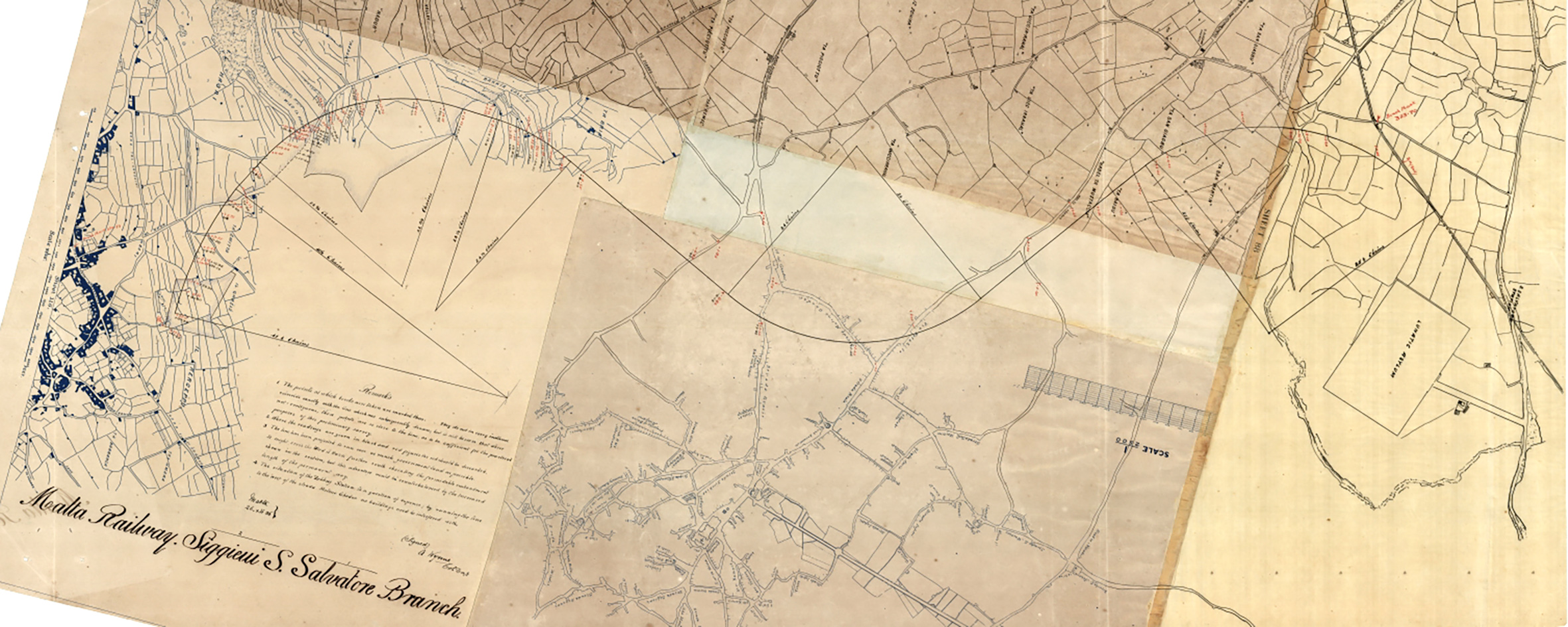

Perhaps now enthused by the potential of developing the railway network, Government commissioned a evaluation by Captain E M Woodward to look at new opportunities. His report, delivered in August 1896, identified four branches that could be beneficial. Two of the proposals would link to Zebbug, a short line from San Salvatore station, and the other from a junction at Blata I-Bajda and through Qormi. The other two lines to be considered connected to Mosta; one would connect to the existing railway at Birkirkara through Lija, the other at a junction near San Salvatore. £20 was allocated to the conducting of further surveys on the two most beneficial proposals, one to each destination. Government were keen to offer guaranteed profit of 2.5% for any local firm who would undertake works, but , apparently, to little interest.

Despite none of the recommended branches finding favour, Woodward and others scoped-out a series of other proposals over the next three years, including two plans in 1896 and 1897 to reach Siggiewi, first from San Salvatore and later through Qormi and Zebbug; an 1897 plan to reach St Paul’s Bay through Mosta; and a final effort in 1897/8 that sought to bring the railway to Sliema. None of these plans developed off paper, perhaps due to the ongoing struggle to complete the comparatively short extension beneath Mdina.

The tunnel below the Citta Veccia had fallen into difficulty when shafts dug down to excavate it encountered clay. This was harder to excavate than limestone and required the temporary propping and permanent lining of the tunnel to prevent it collapsing. It was an unforeseen inconvenience, one that caused the final cost to escalate to £20,000. Gradually, spoil was dug out and dumped to form the huge embankment across the valley in the direction of Mtarfa; Rock excavated from the purpose-built access road from Rabat would also join it. This road passed beside the museum building erected over the Domus Romana, and was in fact dug through part of the archaeological site. This would see the new station christened “Museum”, being more convenient to that side of the valley than Mtarfa.

The station building was already complete and waiting for use before work forming the embankment was finished. Eventually, the tracks were laid, walls and railings erected, and platforms planted, ready for an official opening on 11th June 1900. Sadly, so far no photographs have surfaced of what was clearly a day of great expectation and excitement. Scheduled for the cooler air of the late afternoon, the special train departed at 5:20 conveying dignitaries from Valletta in eight first class carriages. It paused briefly at Attard where His Excellency the Governor joined the train with Lord Strickland. At Notabile the Vicar General blessed the new works before the train restarted through the tunnel under Mdina. Emerging on the other side bands played “God Save the Queen” as the train drew into the platform.

His Excellency was recorded as being “highly pleased” with the works, having been toured around the station precinct and Gheriexem bridge by Buhagiar. The Governor’s speech detailed some statistics of the new extension before thanking Mr Buhagiar for his activity and energy. He then declared the Mtarfa extension open, at which point, led by Buhagiar, the crowd broke into three cheers. The invited guests then retired to one of the waiting rooms where refreshments were laid on.

The Daily Malta Chronicle proclaimed: “The station with its marble floors, the spacious waiting rooms, the veranda and ingress and exits, the well laid grounds with a fountain in the middle with four bronze dolphins (the work of the Railway technical laboratory) throwing water, the plants and trees of this station [is] an ideal one.”

The optimism surrounding the opening of the new station was dealt a heavy blow the following year when fares were increased: the only time this ever happened in the 39 years of Government ownership. Though it was resisted by the Council of Government, fares rose by a penny for First Class, and a halfpenny on Third Class. The members voted for fares to remain as they were, but this was vetoed by the Governor who recognised that the railway needed to sustain itself, particularly in the face of increasing fuel costs. Profits had been gradually dropping over the years, though the railway’s extension had proved profitable. Passenger numbers took an immediate hit, but gradually recovered.

The opening of the Mtarfa extension heralded a decade of renewal for the railway. Freed from the bind of completing the extension, Buhagiar embarked on a flurry of new projects. The old station buildings, always inadequate, were now put to shame by that at Museum. A campaign of rebuilding continued over the next ten years. This began with the replacement of the platform building at Hamrun, a project tied to the further extension of the engineering works. The station building was rebuilt based on the model of Museum station, with high ceilings, generously sized waiting rooms, handsome architecture, and a large new canopy.

The engineering works and school established at Hamrun had been an incredible success and met with universal approval. Its teaching was overseen by Professor William Nixon. He was a London University engineering graduate who, In 1905, took up the chair in Mathematics and practical engineering at the University of Malta. He accepted the additional position as superintendent the railway’s technical school soon after. The buildings, staff, and apprentices had quickly proved their worth, even being able to service the demands of other Government departments. The capability of the works was proven by the transformational outshopping of engine No.4 in 1897. Although it had taken a long time, the engine had been entirely overhauled and virtually rebuilt “constructed from available material adjusted and refitted”. It was unrecognisable from its original appearance, even having been turned 180 degrees to face Mdina like the other locos. It stood as testament to the skill and ability of the works, no doubt contributing to Government’s agreement to commit further investment.

By now, on finding the Beyer Peacock engine No.7 combined power with economy, the Railway had purchased two more, with a fourth arriving in 1905. Buhagiar’s initial plans for Hamrun included the expansion of the railway yards to twice their size, perhaps in anticipation of some never-realised new branch line to service, with huge new sheds for carriages and engines. Land was assembled for this plan and work was even started on shed, but eventually discontinued.

What was realised was the doubling in size of the works, their crowning glory being the ornamental new entrance with its paired archways giving something of a triumphal effect to the endeavour. This ambitious work began in 1901. On completion, Buhagiar was able to report to Government in 1904 that “the enlargement of the workshop at Hamrun has now been completed and the improvements in the· buildings and the new appliances added have proved of great advantage both from an economical and an engineering point of view; all works in connection with the repairs of locomotives and carriages being now carried out in a more satisfactory manner and at a cheaper cost than before.”

Details remain obscure for the rebuilding of Notablie station. It involved the construction of new offices at the level of Racecourse Road with broad steps down to the lower level, and the rebuilding of the platform building on the new improved model. It appears this work happened along with the widening of the station ramp and platform extension in around 1905.

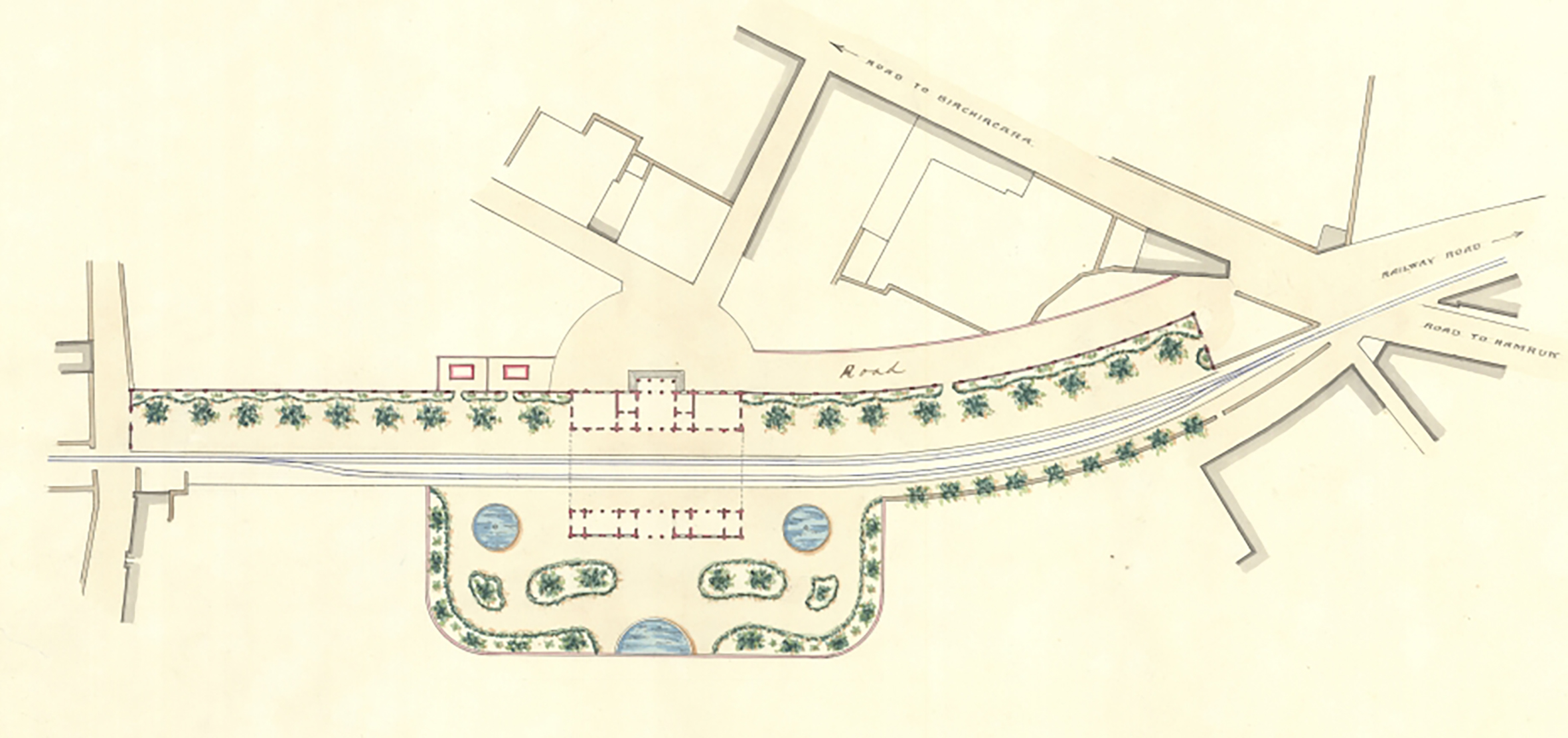

Buhagiar had a vision for the railway’s stations – that they should be as much a visual delight as functional; To achieve this, he transformed the platforms into gardens. This was probably inspired by British railway practice, where competitions were regularly held for the best displays, but Buhagiar went further, making extensive use of trees for shade and shelter, and expending significant energy and money on integrating garden infrastructure into all station refurbishments under his control.

The first known evidence of this strategy was the planting of a series of carob trees along the platform at Attard Station in 1897. These were celebrated with a small cast iron plaque explaining they’d been grown from seed at Ta Xbiex Villa. At about the same time, a large number of trees were planted at Hamrun, lining the back of both platforms with a further row along the station boundary beside the old carriage shed. By 1900, the original short platforms at Birkirkara had also been lined with trees, flowerbeds being an additional innovation. Notabile was also planted with a sheltering belt of trees along Racecourse Road and other shrubs.

By the time Museum station was designed, Buhagiar was able to confidently include extensive landscaping plans for planting the platforms, approach road, and even the banks of embankment and cuttings. The strategy of greening the stations was sufficiently widespread along the line by 1901 that, at the annual flower show in Argotti gardens, there was a dedicated class introduced for “cut flowers from Railway Stations”. By 1917, all above-ground stations had been enhanced with trees and flowerbeds (It’s not known about Balzan, though it seems unlikely it would have escaped when all other intermediate stations were planted). Gardens would again be key to the Railway’s last great project: the rebuilding of Birkirkara and Attard stations.

The station beautiful: Birkirkara and Attard rebuilt.

The railway had already been bruised when planning to rebuild Birkirkara in 1894, only to have the rug pulled from beneath them when Government funding was withdrawn. The station was one of the busiest on the line, but had terrible facilities and platforms barely long enough to handle trains. It was increasingly an embarrassment and off-putting for passengers. Attard was even worse. Only equipped with a tiny shelter meant for halts, it provoked many complaints from users. Even with the railway’s supporter, Lord Strickland, living almost next door, it had received negligible investment.

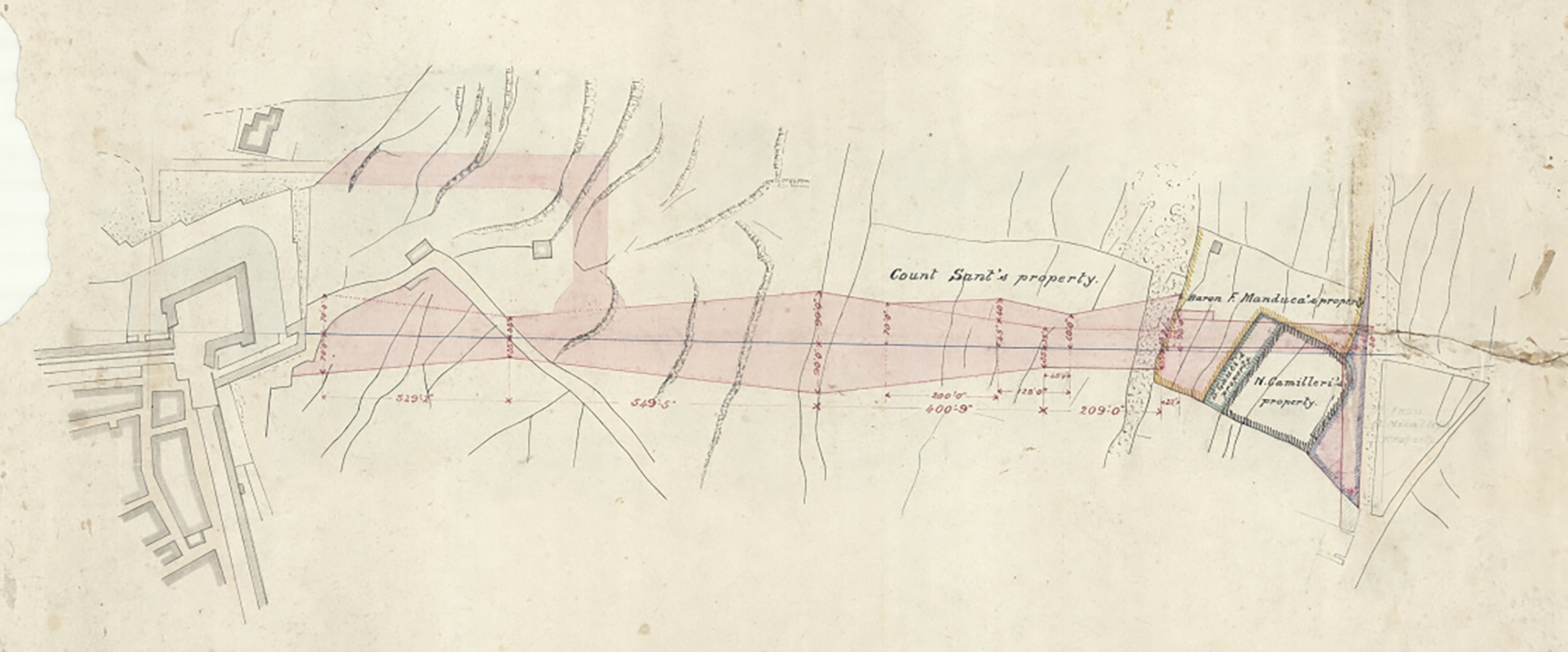

In 1900, there was a concerted effort to acquire land at Attard for a new station. Buhagiar kept the hope of rebuilding Birkirkara alive, producing several extravagant designs in 1902-3. A similarly extraordinary scheme was drawn-up for Attard in 1904. These were all wildly over-ambitious, but helped inform what was to follow. For Birkirkara, this meant two things; firstly the integration of landscaping on an exceptional scale, and secondly the movement of the station facilities westwards from their original site. At Attard, plans would focus on a broad new strip of land on the opposite side of the line to the old station platform, where there was space to provide generous new facilities.

After years of delays, the projects were eventually brought forwards together in 1909. When finished the following year, Birkirkara had been almost completely rebuilt. It now boasted a generously proportioned new set of waiting rooms and ticket office, a fine station canopy, extensive platforms landscaped and planted along their length, and an extraordinary hanging garden along its southern boundary. The old building was then demolished.

Attard was finished later that same year. Catering for a smaller population, it offered a more modest building separated into First and Third Class waiting rooms, a separate ticket office at the station entrance, and more verdantly appointed gardens. Its old station shelter was also demolished. The redevelopment of both these stations carefully protected the earlier trees and gardens planted a decade or more before.

The rebuilding of Birkirkara and Attard completed the scheme of station renewal begun under Gatt’s management but reached new heights in Buhagiar’s hands. Despite the scale, ambition and confidence of these last two stations, all was not well with the railway; They would be its last major project. At the same time as the new stations were being applauded in the press, Buhagiar was forced to cut costs and exploit every opportunity to bring in revenue.